Un Homme Qui Dort is a 1974 film based on a short novel of the same name by the French author Georges Perec, published in 1967. Perec himself collaborated on the adaptation of his work with the director Bernard Queysanne, so this can be seen as an authentic translation of his ideas and intentions onto the screen. Perec loved to play linguistic games. His novels and stories are as much about language and its structures, the way in which they shape our view of the world, as they are about narrative and character. He was a member of the Oulipo group. The neologism Oulipo was itself derived from a linguistic game, a condensation of the opening letters from the grand banner L’Ouvroir de Litterature Potentialle. A rough translation would be ‘the workshop of possible stories’. The group set restrictive parameters and delimiting rules around the use of language, making a game or puzzle of the art of writing and storytelling. The skill lay in creating something meaningful rather than merely mechanical, dryly mathematical or annoyingly clever from the means available. The imagination could be channelled down new paths and surprising byways by the application of such strictures.

Georges PerecPerec’s most extreme gesture in this mode was his novel La Disparition (The Disappearance), published in 1969, in which the letter ‘e’ was entirely absent, as if it had been erased from the alphabet. In an equally astonishing intellectual feat, which took the art of literary translation to new heights, the author and screenwriter Gilbert Adair produced an English language version of the book, an endeavour which was in effect an Oulipoean game in itself. Perec also wrote Life: A User’s Manual (1978), whose chapters were all based in the individual rooms of a Parisian apartment block, and whose narrative structure was largely determined by the moves of a chess game plotted out on a diagrammatic chart of the building in question.

Un Homme Qui Dort was written before Perec joined the Oulipo elite, but clearly points to his interest in linguistic experiment in its use of the second person singular throughout. This creates both a sense of distance and of intimate address, implying a certain narrative omniscience and even control whilst inviting the reader to identify with the nameless protagonist (the ‘you’). In its original French incarnation, the ‘tu’ has additional nuances, implying either comfortable familiarity and intimacy or a belittling condescension reserved for someone too insignificant to merit the formal, polite ‘vous’. The equivalent of talking to someone as if they were a child, a bit simple.

In the film, passages from the novel are read out by a neutrally-toned narrator. This is a literary adaptation in which words and images remain, at some level, separate. There is no dialogue and little natural sound in the film. It is, to all intents and purposes, silent, with recorded sound subsequently overlaid. The words came first, but it often seems as if they are providing a commentary for pre-existing images, rather than the images giving visual form to the words. For the English-language version, Shelley Duvall voices this neutral tone perfectly, and also captures the quality of reverie which permeates the film – a reverie which can bring small details into sharp focus whilst blurring the wider world into a confused fog. Her voiceover recalls her character Millie in Robert Altman’s 1977 picture 3 Women at the end of the film, when her ceaseless stream of empty babble ceases and she speaks in similarly abstracted tones – a voice of almost inhuman clarity. In Un Homme Qui Dort, however, it is not without an undertow of pity and compassion. The narrative voice articulates the protagonist’s otherwise impenetrable inner life. It almost seems to direct him at times, and is an aural manifestation of the surrendering of his free will. But it could also be heard as a voice wholly unallied with his own consciousness and being; a voice which is trying to break through the into the sphere of his isolated orbit, to make him perceive his lonely world with greater clarity, and thereby to prompt him to save himself. This voice is even given watching eyes: the surveillance cameras which are seen at various points throughout the film, swivelling and focussing on their iron pedestals to observe his passing below.

We first encounter the ‘tu’ of the film in his small garret room, the archetypal Parisian dwelling of the struggling artist, existential philosopher or (as in this case) penniless student. He experiences some undefined moment of inward ontological crisis in which the quotidian observances of his life become drained of meaning or purpose. Attempting to approach what is essentially a breakdown with the intellectual rigour and control of an empirical philosophical investigation, he decides to systematically reduce his existence to some absolutely fundamental level. To this end, he strips away all personal and social elements and condenses essential functions into repetitive, reflexive actions, which are performed with mechanical affectlessness and lack of conscious thought. These actions are precisely delineated and enumerated – the 6 socks washed in a pink bowl, the tasteless steak eaten at the nondescript bar – until they become overdetermined and wholly detached from the broader canvas of actuality.

Un Homme Qui Dort could almost be seen as a satire on fashionable existentialism, of young men who adopted the hip pose of alienation and a studied and verbose disaffection with the superficiality of modern society. This is the kind of alienation which fed into the countercultures of the 60s, and into the rock music which was its soundtrack. The protagonist even looks a little bit like Eric Burdon from The Animals. There may be an element of that. But this is also, despite its second person narrative voice, a very personal film, deriving from a very personal novel, which draws on Perec’s own experience of mental breakdown as a young man. The remove granted by the narrative device may have been necessary for him to achieve a certain distance from and objectivity towards those painful experiences. The protagonist’s state lies within his own fragmented self, ultimately arising from his failure, or refusal to connect with the world. In this case, the problem is located within the individual rather than in society. The Escher print on his wall provides a diagram of the confused knots of his mind, stairways climbing the walls at impossible, self-contradictory angles which are at odds with the universally held, empirically verifiable laws of the universe. And yet there they are, seemingly abiding by their own hermitic logic.

The protagonist self-consciously cultivates his mental breakdown as if it were a reaction against the imbalance of the modern world. The controlling limitations he imposes upon his own existence (Oulipo rules applied to real life) follow on from an initial moment of slippage, of consciousness falling out of sync with what is expected of it. He pretends to himself that this is something which can be managed, an act of self-collusion which denies the possibility of help from others. He is in effect declaring himself to be self-contained, a monadic entity. There’s a strong current of egocentricity to this choice. As the narrative voice in the book declares, he becomes, in his own mind, ‘the master of time itself, the master of the world, a watchful spider at the hub of your web’. Out of such willed disconnections are destructive power fantasies made manifest. On the other hand, this is also an act of self-erasure, a depressive stumble towards complete disappearance, the invisibility attendant upon ‘your vegetal existence, your cancelled life’.

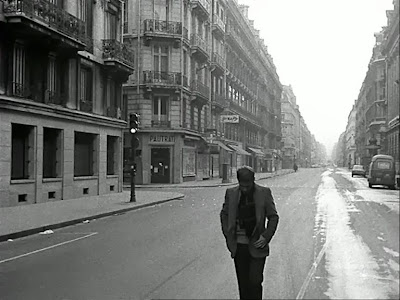

Having withdrawn from human society, the protagonist becomes an observing eye, wandering the streets of the city. The city becomes a reflection of his inner state, a mental street map. We get to see it afresh through his detached, floating viewpoint. This is the Paris of the surrealists - of depopulated dawn streets; canalside paths lined with neat, regularly spaced trees which appear to lead to arboreal gateways at the vanishing point; narrow, café-lined evening back roads and broad, stately boulevards; drowsy afternoon cinemas; empty shopping arcades; spiralling stairwells; and parks in which old men sit with statuesque stillness, lost in inward contemplation. It’s a city which seems full of immanent meaning, of mysteries on the verge of revealing themselves. A humming, distant drone infuses the senses with sense of the interconnectedness of the material and the immaterial, an intuitive mysticism made audible. The protagonist sits for ages staring raptly at a knot in the bark of a pavement tree. Its complex detail seems to open up whole interior spaces, new worlds for him to get lost in, like a tree in a Magritte painting. Magritte, in fact, is something of a presiding spirit in the film, along with de Chirico.

But in the end, no Buddhist-style enlightenment is afforded by the retreat from the world and its sensory pleasures and comforts, the erasure of desire and emotional attachment. The point at which dreamlike detachment descends into nightmarish disconnection is indicated by a switch to a scorching, overexposed pictorial style. Details become blanched, contrast bleached out, a visual analogue of a mind losing any element of cohesion or self-control. Expressionistic sound design further adumbrates this frightening state. Whereas before, the distant drone accompanied blissed-out, solitary perambulations, now there are irritating, repetitive tapping and knocking sounds. They are amplifications of the permanently dripping tap in the corridor outside his room, and of his own neurotically drumming fingers. These sounds mock the reductive routines which have come to measure out the daily progress of the hours. Close-up shots of him chewing his fingernails are interpolated into the increasingly frenetic, off-kilter rhythms of the editing, creating an uncomfortable, edgy ambience. This is no longer an experiment in detachment, but a descent into a genuine breakdown. The controls are falling away, the self-delusory barriers crumbling. Any idea of penetrating beyond the surface of things, of attaining some elevated vision, is burned away in the harsh magnesium flaring of burnt-out synapses.

La Reproduction Interdite (Not to be Reproduced), the Magritte print on the wall above the head of his bed, turns out to have been a warning. The typically anonymous Magritte figure stares into a mirror, but the reflection is of the back of the head which we see in the frame. Such intense self-reflection doesn’t reveal a true image of some essential core of being; just another blank surface, a short back and sided void. A more constructive direction lies perhaps in the unobtrusive image on a small postcard at the foot of the bed, neglected and incidental. It’s a portrait of the medieval scholar Erasmus. He serves as a symbol of contemplation, learning and curiosity, but also of a desire to travel, to share knowledge and to delight in the exchange of ideas in the company of others. To connect with the world, in short.

The film ends up as an essay in the dangers of falling into the illusion that the individual intellect is sufficient unto itself, that it can be a self-contained, monadic world. In the final shot of the film, the camera pulls back from the protagonist as he wanders lost and bewildered down a dark, sloping alleyway (bringing to mind those haunting late photos of Nick Drake on the pathways leading to Hampstead Heath). The city is now a maze inside his head, locked and turning endlessly in on itself. The camera steadily zooms out until we realise we are looking at precisely the same cityscape which opened the film. We have turned full circle and gone nowhere. The city remains as mysterious and unknown as it was at the beginning, as does our nameless protagonist. His explorations have, in the end, been shallow and self-deluding, revealing nothing. Now he must find help, a guiding thread to lead him back out of the labyrinth.

No comments:

Post a Comment