Solarference are a duo, Nick Janaway and Sarah Owen, who make electronic music which uses traditional folk song as its familiar source and emotional anchor. The resulting hybrid, which the name poetically evokes, successfully casts both forms in a new light. It reflects both the rural character of their Westcountry background and the experimental musics which they encountered in the course of an art school education in London. This blend of musical traditions follows an oral lineage back through the generations and introduces an exploratory use of new technologies, drawing on paths forged in the era of post-war modernism. Such a superimposition of old and new raises the spectre of hauntology, that awkward academic term which has been applied to certain kinds of music and graphic design invoking the ghosts of memory inhabiting a post war period which ended with the onset of the 80s. These ghosts are also often imbued with more ancient layers of time and folk memory, reflecting the fascination with the deep history of Britain which was prevalent in 1970s culture. It has to be said, the term often seems to function largely as a label which its supposed practitioners can reject or express bewilderment as to the meaning of. Whatever terminology is applied, however, the drawing together of the old songs, which seem to rise with uncanny familiarity from some collective strata of the unconscious, with electronic sounds and digital concrète manipulations redolent of an age super-saturated (and perhaps sated) with technological magic, produces a bewitching and very powerful effect.

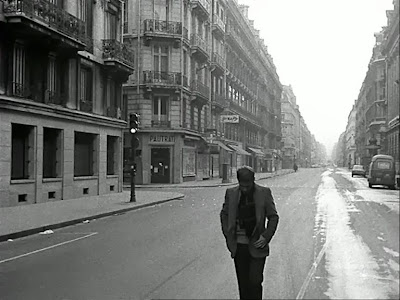

This fusion of old and new was lent a further dimension on March 9th at the Phoenix in Exeter when they provided a live, semi-improvised accompaniment to the 1920 film adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s tale of hubristic scientific alchemy and the duality of the human soul, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. The digital projection was taken from a poor quality print, the shadows and fog of the gaslit London street scenes rendered even more murky and obscure by the abrasion and chemical erosion of time. This made for an interesting disjuncture with the duo standing to the side of the stage beneath the screen, their studiously intent features illuminated by the megabyte glow of their lectern-perched laptops. The impression of eras facing one another across a century’s gulf, analogue and digital interpenetrating in some interstitial zone beyond normal temporal bounds, was reinforced by the Victorian/Edwardian casual garb which the two musicians wore for the occasion.

The film, with John Barrymore in the dual lead role, was the most prestigious of three versions made in 1920, and really served to establish the portrayal of the Jekyll and Hyde personae, and set the accepted tone of the story, in the popular imagination. Jekyll is upright and observant of conventional Victorian middle-class social etiquette; Hyde is bent into a devolved, simian stoop and is amorally intent on sating any of the sexual appetites of venting any of the violent urges which define his being. This idea of Hyde as the embodiment of the repressed side of the superficially noble and respectable Dr Jekyll which physically manifests itself as an ape-like monster was first put forward in J.R.Sullivan’s 1887 theatrical adaptation. It was not an interpretation which pleased Stevenson himself. But his creation was soon developing into something beyond his control. The film drew on this sensational and highly successful stage version, and the transformation scene became the central dramatic moment, a testing challenge for actor and special effects artist. There is a definite aura of the limelighted stage suffusing the 1920 film Another faultline between the ages is evident here – the grand world of the late Victorian theatre suddenly fixed on the screen in the new global medium of the movies.

In this instance, it is a rather less successful conjunction. Many of the drawing room scenes are stilted and dull, and John Barrymore’s broad gestural acting can come across as the most overcooked ham in the unforgiving close-up glare of the studio arc lights. His transformation scene in particular raised unfortunate titters and snorts of derision. He mugs frantically, grasps his throat and seems to throw himself bodily about before finally taking a spectacularly melodramatic dive onto the laboratory floor. His performance as Hyde is at times memorably flesh-crawling, however. His lank hair is clammily pasted to his temples and his skull disturbingly distended (a phrenologist’s dream, or nightmare) in the shape of a coconut husk or a bulbous spider’s abdomen. There is indeed one truly horrific fever dream sequence in which a giant, hairy spider with Hyde’s leering face at its head clambers stiffly up onto the four poster bed in which Jekyll restlessly sleeps, crawls over his body and settles down to merge invisibly into it. The figure who then wakes up is, of course, Hyde.

Solarference draw on the wide folk ballad repertoire which mournfully tells of false love and tragically thwarted romance to accompany the scenes involving the ‘pure’ object of Jekyll’s repressed affections and the musical hall artiste (played by Nita Naldi, the future co-star of Rudolph Valentino in some of his biggest pictures) who falls prey to Hyde’s unsubtle and ruthlessly calculating advances. Many of these ballads have appeared on the death-haunted late 60s albums of Shirley Collins (The Sweet Primeroses, The Power of the True Love Knot and Love, Death and the Maiden), on which she was often accompanied by the hauntingly fragile piping of her sister Dolly’s home-built portative organ. It’s possible that it was here that Solarference discovered the songs – a fine source if so. They certainly create a cohesive, melancholic mood which emphasises the female aspects of the story’s tragic trajectory. Barbara Allen and The Sweet Primeroses are both songs of false and violently opposed love. The latter has a verse which begins with the line ‘So I'll go down to some lonesome valley/Where no man on earth shall there me find’, which is used for some of the darkest parts of the story. The words are cut and repeated, creating a truncated echo which makes it seem as if we really have descended into that deep, desolate valley. Barbara Allen, a tale of love scorned and mocked by its object, is particularly appropriate for the scenes in which Hyde taunts and dismisses the musical hall artiste whom he has reduced to his domestic drudge, and whom he later encounters in the opium den. Go From My Window also has the highly apposite line ‘oh the devil’s in the man that he will not understand, he can’t have a harbouring here’. Solarference have evidently chosen these songs with great care and attention to detail.

Black Ships Ate the SkyThey also use the old Charles Wesley hymn tune Idumea to stunning effect. Its opening question, ‘and am I born to die, to lay this body down/and must my trembling spirit fly into a world unknown’, once again highlights the tragic nature of the story, its inexorable progression towards a fatal conclusion. But it also points to the spiritual anxieties which underlie Stevenson’s stories. The concern for the state, or even the existence of the soul in an age of scientific breakthrough – of the telescoping of time into geological millennia, and of psychoanalytical and evolutionary theories which began fundamentally to change humanity’s perception of itself and its position in the scheme of creation. The song was also incorporated into the eschatological worldview of David Tibet and his Current 93 project. It was sung by a number of people on the Black Ships Ate the Sky album, one of whom was Shirley Collins.

Much of the soundtrack was created on the fly from numerous ‘concrète’ sources, sounds recorded and instantly transformed by a powerful and swiftly responsive sound-editing programme. Comb teethe were thumb-raked, miniature music box handles cranked, the bodies of glass bottles chinked and their mouths breathily blown across, Chinese-sounding flutes piped, paper slowly torn and a dulcimer plucked. The resultant noises were expanded, multiplied and dispersed into rich and colourful fogs of sound. The principal source was the human voice, however, the vast potential of which was used to produce whispers, clucks, slurps, sighs, shhhhhs and grunts. These sometimes lent the sequences they accompanied an inner soundtrack, as if they were sounding out the film’s subterranean layers of meaning. For the scene in which Hyde enters the Limehouse opium den, for instance, the recorded voice was atomised, replicated and scattered. This expressed both the fragmentary, partial nature of Hyde’s persona, and the dislocated dreams drifting up from the squalid pallets of the dazed pipe smokers. For the dinner party scene in the Victorian parlour, we heard a layered swarm of sibilant whispers. They were somewhat akin to the susurrus of inner voices heard by the angels in Wim Wenders’ film Wings of Desire as they watch over the readers in the Berlin State Library. This parlour whispering was interspersed with slurping, sucking and the smacking of lips, suggesting that this was a milieu in which the appetites for food and gossip were indistinguishable.

Luciano Berio and Cathy BerberianThe extended vocal techniques, subsequent electronic transformations and their expression of inner states brings to mind the 1960s and 70s collaborations between Italian composer Luciano Berio and his then wife, the soprano singer Cathy Berberian. Her extraordinary vocal performances on Visage and Sequenza III take the listener on an intense, kaleidoscopically shifting voyage through a dizzyingly fragmented mirrorworld of psychological moods. It feels discomfortingly at times like experiencing a monumental breakdown from the deep interior of an individual psyche. Berberian also sang Berio’s more straightforward Folk Songs suite, which gathered together folk melodies from various countries (and included the modern standard Black Is The Colour of My True Love’s Hair), providing a further parallel with Solarference’s blending of the experimental and the traditional. Berio would have created his vocal collages through a thousand cuts and splices of tape, of course. A modern artist who has used less fiddly and laborious (although in their own way equally painstaking) digital means to make music from the isolated, compacted and stretched sounds of the human voice is Oneohtrix Point Never (aka Daniel Lopatin), whose latest album, R Plus 7, is another point of reference. The isolation and reproduction of fragments of human utterance also served to create syllabic rhythms, which provided a propulsive sense of momentum to some of the film’s more dramatic moments.

In the second part of the evening, Solarference returned in modern day civvies to play a small selection from their album Kiss of Clay (the chilly phrase deriving from the haunting graveside song Cold Blows the Wind). The record is, perhaps understandably, more solidly song-based, with the experimental elements restricted largely to creating background colour and atmosphere. Live, however, those elements came to the fore, and the songs were allowed to stretch out into more unusual shapes before returning to their melodic harbour. It was a genuinely thrilling and innovative balance of the traditional and the experimental. The harmonies were lovely in themselves, particularly on the bilingual Welsh song which they ended with, Ei Di’r Deryn Du. This is a fusion music which really works in exciting ways, without sounding remotely contrived or forced. It manages to unite the seemingly alien and irreconcilable worlds of Xenakis, Stockhausen and Pierre Henry with those of Martin Carthy, Shirley Collins and Anne Briggs. The folk tunes and the tales they tell form the human heart, the familiar core, but they are moulded into all manner of new and strange configurations, whilst never losing their essential character.

After the final song, we were invited to come and look at the technology involved, and ask any questions which might occur. Looking at the sound wave patterns and the shadowed sweeps which gathered selected splinters up to transform them, it became evident how intuitive and visually cued the process was (once thoroughly learned and absorbed, of course). This is sonic painting or sculpting in real time, a digital development of the ideas of drawn sound synthesis which Daphne Oram in Britain and Eduard Artemiev in the USSR experimented with in the 1970s. This invitation to come and talk and see how things were done pointed to a real desire on the artists’ part to reach out and communicate their own excitement about their music and the ideas behind it. It was an excitement and daringly exploratory spirit which came across forcefully in the committed and immensely enjoyable performances they gave at the Phoenix in Exeter.