There have been two alternative post-catastrophe worlds on view in London galleries of late, both involving collaborations between writers and visual artists. Tacita Dean’s JG, inspired by the works of JG Ballard, was on show in the Soho Frith Street Gallery (confusingly not in Frith Street itself, which became apparent after a fruitless stroll along its length). Once found, in the wonderful 17th/18th century environs of Golden Square, it offered a rather imposing façade, with a front entrance seemingly designed to give the impression that the gallery was closed, as if to put off the uncommitted visitor. The basement bunker would have been a fittingly Ballardian place to project the film, with its achingly cool exposed concrete, but it was in fact shown in the street level gallery, just to the side of the busy office space. Memory Palace at the V&A was a visual realisation of a science fiction story written by Hari Kunzru, set in a de-technologised future in which a new form of fundamentalism has become dominant. It took place in a specially partitioned off area whose darkened spaces with their high dividing walls were designed to usher the visitor into this newly created world, shutting them off from the familiar one beyond.

Tacita Dean’s meditative film JG has its origins in her correspondence with JG Ballard, and particularly with their mutual fascination with Robert Smithson’s renowned work of land art Spiral Jetty. The film acts both as a reflection on Ballard’s work and as a personal valediction for her friend. It depicts a Ballardian landscape of rich desolation, a surrealist plane onto which significant objects can be placed or into which geometrical patterns can be carved. Both carry meanings which communicate directly with the subconscious. Dean uses digital superimposition and split screen techniques to achieve the effects which Ballard and his beloved surrealists created through prose, paint and various forms of collage. She found the perfect landscapes in Death Valley, Great Salt Lake, Utah, Monolake, California and other places in the US. Signs of human habitation are few and far between. We see industrial machinery, slow-moving trucks and trains on the horizon or a worksite hut with a light on suggesting recent habitation. But there are no actual human figures. Salt deposits, dessicated and rock-strewn vistas, milky rivulets and lakes tinted an unnaturally royal blue by mining deposits suggest the transformed planets of The Drowned World, The Drought, The Crystal World and Vermilion Sands. Swollen sunsets hanging above crumbling cliffs beyond the edge of the lake are suggestive of The Terminal Beach and other stories in which entropic scenery anticipates the winding down of time and human consciousness.

There are brief readings by Jim Broadbent (chosen for his initials?) from two early Ballard stories, The Voices of Time and Prisoner of the Coral Deep. They are sparse and spaced widely apart, reflecting the primacy of landscape (be it inner or outer) over dialogue and character in Ballard’s work. Both stories involve an altered temporal perspective – an entropic winding down of the evolutionary process in The Voices of Time and a shift into geological scale in Prisoner of the Coral Deep, which takes place on the Dorset shore. The image of the spiral is a recurrent one in Dean’s film, superimposed over water or rock. It makes reference both to the fossilised shell which acts as a trigger for the interior timeslip in Prisoner of the Coral Deep, and to Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. Ballard wrote about this work, which fascinated him so, in his essay Robert Smithson as Cargo Cultist from 1997 (unfortunately just too late to be included in his essay collection A User’s Guide to the Millenium). Smithson’s rock spiral, extending out into Salt Lake in Utah, was deliberately constructed at a site in which the waters stilled within its coils would be turned red by algae, contrasting with the vividly unreal colours surrounding it, the legacy of effluent from the abandoned industrial plant. Robert Hughes writes about it in American Visions, his history of American art. He notes how ‘Smithson had been preoccupied with entropy’, and that his ‘imagination had a strong component of the higher sort of science fiction, such as the apocalyptic, time-drenched landscapes of JG Ballard, whom the artist read avidly and admired’. The admiration was mutual. In his brief essay, Ballard hitched Smithson’s works to his own perennial concerns. He wonders ‘what cargo might have berthed at Spiral Jetty’ and imagines a ‘craft captained by a rare captain, a minotaur obsessed by inexplicable geometries’. He suggests that ‘his structures seem to be analogues of advanced neurological processes that have yet to articulate themselves’ and that ‘his monuments… (are) the ground plans of heroic psychological edifices that will one day erect themselves and whose shadows we can already see from the corners of our eyes’. The jetty has long since been washed away by the geological and tidal forces of erosion. It was always intended to be a piece which lasted little longer than a handful of years, offering a condensed vision of the processes of deep time. Dean resurrects its spirit in the place where it was briefly a curious feature of the landscape, a mystery which Ballard suggested she might try to solve.

Robert Smithson - Spiral JettyThe colouring of the pools in Dean’s film by mineral extraction and the outflow of industrial processes echo this transformation of the environment by a mixture of human and natural agency. We also see a digger at the start of the film scooping out geometrical channels in the rocky desert plain. This relates both to Smithson’s extraction of materials for his spiral, and to the compulsion which drives Ballard’s characters to make patterns, abstract markings in the landscape which express some interior symbology. In The Voices of Time, the protagonist expends some of the last of his dwindling energy on customising the concrete bunkers, towers and targets of an abandoned Air Force weapons range into a monolithic mandala in which he can take his own insignificant place. Another character carves patterns in the floor of an empty swimming pool ‘to form an elaborate ideogram like a Chinese character’. The empty swimming pool is another favourite Ballard image, which his autobiographical novel Empire of the Sun suggests may derive from childhood memories. The blue rectangles of water superimposed on desert and lake backdrops can be seen as Dean’s recognition and adoption of this motif. The spiral is sometimes set against geometrical landscapes, curling, natural forms contrasting with the rectilinear patterns of human design. It also depicts a journey inward or outward, furling or unfurling, It connects the inner to the outer landscape, the body of water to the land, and also hints at a nonlinear or vastly expanded view of time. The film’s narrative quotes from Prisoner of the Coral Deep, the protagonist of which contemplates a fossilised shell and comments ‘if only one could unwind this spiral it would probably play back to us a picture of all the landscapes it’s ever seen’. It would be like an unspooling reel of mineral film.

This is one reason why Dean makes the film strip visible in several scenes, giving it a sense of non-digital materiality, of time unwinding as a reel of film does. And, of course, a film can be rewound onto its spool, time stored in readiness for another cycle. The visibility of the film strip also alludes to the watchers and observers, directors and conductors present in many of Ballard’s stories. Their presence beyond the frame is also hinted at by the occasional click of a shutter or whir of running film. Gurus and psychopaths are often on hand to guide the protagonist along inward paths, helping him (and it is always him) to find his true place at the heart of the catastrophe, or to realise his own unique psychopathology to its fullest extent. The screen is split at times, images competing for our attention, forcing us to splice our own coherent pictures together. This makes us aware of their mediated nature, and points to the media landscape which was increasingly central in Ballard’s late 60s work. The split screen and sudden edits also create something of the feel of the fractured narratives in his ‘condensed novels’ of this period, many of which were collected together in The Atrocity Exhibition. Creatures making scurrying or scuttling appearances make further reference to the two source stories. A lizard alludes to the transformation of the siren of geological time at the end of Prisoners of the Coral Deep: ‘on the ledge where she had stood a large lizard watched me with empty eyes’. An armadillo, meanwhile, stands in for the desert animals in The Voices of Time who are mutating in anticipation of a steady increase in solar radiation, growing hardened, lead-lined shells. Dean’s film has a dreamlike quality all of its own, but also acts as a carefully and lovingly compiled compendium of Ballard’s themes and concerns – his grand, intoxicating obsessions.

The Memory Palace exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum derived from a new story by Hari Kunzru. He has created an post-catastrophe science fiction world whose key attributes, both in terms of significant differences from our time and of a future historiography which recasts the present, with ironic or satirical effect, are outlined under clearly delineated headings – proper verb nouns which make the newness of an invented reality readily and swiftly comprehensible. This is often a fault of non-genre authors attempting to write SF or fantasy who take an overly schematic approach which leaves the plans to their thinly constructed worlds plainly visible. Kunzru is no literary arriviste on genre terrain, however. He first came to my attention through an interview he conducted with Michael Moorcock for The Guardian some time ago, in which he revealed his youthful love of New Worlds and the new wave SF of the 60s and 70s. This was a prime period for post-apocalyptic scenarios, which ranged from Angela Carter’s Heroes and Villains and Samuel Delany’s city-based Dhalgren through to some of Moorcock’s Jerry Cornelius stories, Keith Roberts’ dark pastorals The Chalk Giants and Pavane; from JG Ballard’s inner landscapes, cleared of all the inessential clutter of civilisation to M.John Harrison’s savage The Committed Men and John Crowley’s bucolic Engine Summer. The latter provides an interesting contrast with Kunzru’s world in that it is set in a post-literate and post-technological but essentially peaceful and civilised future; a future in which our present is a barely remembered dream. Kunzru reverses the ecotopian trend of the 70s (also to be found in Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time) and presents a green theocracy as a new inquisitorial force of oppression and tyranny in a post-disaster world long stripped of its former technologies.

The schematic outlining of the future world works in the context of the exhibition. Its basic contours need to be clearly and concisely presented in a few easily absorbed phrases. Familiarity with the accompanying story certainly cannot be assumed (I hadn’t read it, for a start). Thus, three ages are swiftly laid out: The Booming, which is our time of globalised capital and lightning communications; The Withering, the period of chaos and collapse in which the story is set; and The Wilding, the deep green future envisaged and worked towards by the ecotopian council known as The Thing in which humanity will diminish and become absorbed into the natural order once more. This will involve a surrender of all knowledge harboured from the time before the Magnetisation, the name for the devastating magnetic storms which brought our technological era to an end. Reading, writing or any form of representation or recording of the world, past, present or future, is outlawed. The Thing wish to create a post-literate world in which humanity returns with dumb humility to take its place in the recrudescent wilderness. But there is opposition.

The protagonist whose progress we follow around the various points of the exhibition space, and through whose perspective we piece together a picture of the world, is one of a rebel band of intellectuals who defy this retreat from civilisation by reviving the old idea of the memory palace. This can be used to create and foster libraries of knowledge within the seemingly unassailable spaces of the mind. The memory palace was a system for remembering facts and ideas by building up a mental architecture, perhaps replicating a well-known building from the external world. Each brick or window or piece of furniture would be associated with a particular node of knowledge, and all would be carefully arranged in categorical order. John Crowley depicts the use of such a system by the Renaissance scholar, scientist and philosopher Giordano Bruno in the 16th century. It leads to his persecution and eventual execution by Inquisitorial forces. Kunzru’s narrator follows a similar path, the knowledge accumulated and stored within his interior architecture a challenge to a different idea of divine order, and by extension of the authority of the priestly hierarchy which propounds it. Our narrator is arrested and imprisoned from the outset of the story. We see his pentangular cell (made here by artists Frank Laws) and peer through the gaps in its walls to the confined space which he expands into his own memory palace. A meagre mental canvas whose every crack and splinter he makes use of. We glimpse some of the pictures which he has begun to project on the dismal, dimly lit brickwork of his prison.

The exhibition space itself was constructed around the idea of the memory palace, with ghost outlines of arching rooftops and windows rising above the partition walls. There was also a kind of junk memory palace in the far corner of the last ‘room’, a church-like bunker built from baled-up breezeblocks of recycled papers. This is a construct of unfiltered information, a conglomerated mass of newsnoise in which anything of value gets drowned out in the undifferentiated torrent.

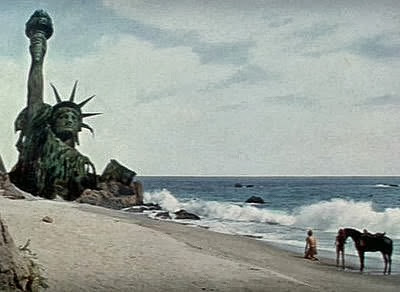

One of the great pleasures of post-apocalyptic stories is seeing or reading about familiar buildings or monuments which have been transformed in some way. Either they have fallen into ruin or they have been used for some purpose utterly at odds with their original function. The Statue of Liberty was always the most popular choice to mark the fall of us all, so much so that magazine covers depicting it half submerged by a great deluge, with shattered crown or lying toppled on its side became something of a cliché. In this exhibition, it is London landmarks which are subject to picturesque ruin and the invasion of the London cityscape by a resurgent wilderness. Nemo Tral’s lightbox prints present these scenes as sacred stained glass images, the new religious order celebrating the disintegration of the steel and glass monuments of the old metropolitan age. Further images of the city overrun are presented in Isabel Greenberg’s digital prints which, like the stained glass, resemble black and white comic book illustrations. The Shard is shattered (hooray), vines entwine the trunk of the Post Office Tower and enmesh St Pancras station, shanty towns cluster in the shadow of the Olympic Stadium and the Barbican flats and walkways rise above a central lake.

A museum cabinet by Abäke contains semi-abstract objects of transparent Perspex which seem to have been denuded of meaning and are on the verge of dematerialisation. It’s reminiscent of the abandoned museum the traveller in HG Wells’ The Time Machine comes across in the future, whose exhibits are all dusty and disintegrating through the neglect of centuries by the intellectually enfeebled Eloi. A later sculpture, which resembles a 3D comic image in boldly outlined black and white, allows us a close-up look at a NHS wagon. Drawn by four foxes, it looks more like a funerary hearse. The stacked up boxes and bottles of snake oils and quack cures on offer, all with voodoo brands offering instant salvation, betoken a retreat from empirical rationalism into magical thinking. Any idea of universal care has long been abandoned, and the NHS letters are nothing more than a totemistic remnant from the past. This is Death’s wagon, spreading the plagues it loudly claims to ward off. It was made by Le Gun – hmm, just an ‘i’ off from Ursula K.

Henning Wagenbreth builds up his view of the old metropolis from brightly coloured wooden blocks. It’s a childlike construct incorporating distinctly unchildlike subject matter. It suggests both a simplified view of the past and a technological tower of Babel which is all too easy to sweep aside into a rubbled heap. Several walls are covered with comic strip panels in austere black and white, resembling Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s V for Vendetta (as originally published in monochrome in Warrior) and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. These told the story of our narrator’s arrest, trial and interrogation, during which he comes face to face (or hood) with his own version of Winston Smith’s O’Brien. The Inquisitorial figures which confront him look like something out of Goya’s Los Caprichos adapted for a British mythos. Perhaps the most impressive work in the display was Jim Kay’s sculpture, a hybrid of altarpiece and museum cabinet of curiosities. The two doors opening out from this wooden cabinet formed a diptych, the first panel depicting the violent collapse of civilisation and the second the post-apocalyptic world. A small drawer, pulled out in front, contained a variety of simple objects sorted into tiny individual trays, the humble beginnings of a curatorial mindset. The centre of the altarpiece was taken by a branching tree of gold, upon which tokens with images of birds were dangled. The difference in the shapes of their beaks made this a sacred tree of diverging evolutionary variation. It alluded to Darwin’s observations of the variations in the beaks of finches made on his world travels which contributed to the formulation of his evolutionary theories of natural selection. Hung on golden boughs, they have become symbols of a new worldview which is more in tune with Charles Frazer’s survey of primitive mythological beliefs than with The Origin of the Species. On the top of it all perches a large crow, a death’s head token held in its beak.

Not everything here worked, but the central idea of artworks bringing an extra dimension to a story was a good one, ripe for further exploration. At the end (and stop now if you intend reading Kunzru’s story) our narrator’s life fades away. But before he dies, he is contacted by the resistance, who speak to him through a tiny crack in his cell wall. They tell him that he can leave one sentence behind for them to take out into the world – one brick from his memory palace. The final panels fade to black. No matter how elaborately constructed, the memory palace fades into nothingness once the mind which has so painstakingly planned and built it ceases to exist. This exhibition memorialises one such imaginary palace with its various works, and thereby points to the way in which art can immortalise aspects of an individual’s unique consciousness, their particular way of seeing the world. At the end, the blank panels morph into a series filled with messages, doodleboards onto which the visitor has been encouraged to add a memory precious to them. The present, with all its Babel of voices, its obsession with constant communication and occult finance, is ultimately seen as a time in which there is still much joy and happiness. This is one of the lessons of the post-apocalyptic tale. We see the seeds of its creation in our own world, but it also makes look at what’s good in that world, what we would miss if it was gone. At the heart of the imagined catastrophe lies an utopian urge.