Friday, 29 August 2014

The Dragon Griaule Stories by Lucius Shepard

Lucius Shephard’s sequence of linked but discrete stories featuring the Dragon Griaule originated in a Clarion Writer’s Workshop in the early 1980s. Seeking inspiration, Shephard went outside, sat under a tree and smoked a leisurely, contemplative joint. As he relates in the 2013 Gollancz Fantasy Masterwork collection of the Griaule stories (which sadly can now be considered complete since Shephard’s death earlier this year) he was visited by the dope-genius revelation ‘big fucking dragon’. And Griaule is indeed gargantuan, the mother of all fantasy dragons, more a mythic alpine landscape of the terrifying sublime than a living creature. From this unpromising seed grew one of the greatest sustained works of fantasy literature of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

The Dragon Griaule is a central presence throughout the stories, but also a significant absence. It is almost wholly quiescent since a duel with a wizard in a past distant enough to have been obscured in the distorting haze of layered myth and history. The traditional elements of heroic fantasy are here reduced to remote memory, twice-told tales and rote superstitions. The dragon is a landscape feature – it’s almost as if it’s been read into the landscape, ridges, rock-faces and caverns given animal form and animist soul. It is a scaled mountain range with forests bristling its back, its head a craggy outcrop and its gaping mouth a dark cave leading down into the labyrinth of its internal system. This sluggishly vital underworld, along with its unique ecosystem, is extensively explored in the second story, The Scalehunter’s Beautiful Daughter. Shepard has a fondness for such vast, enclosed worlds. His novel The Golden is a vampire tale set in an immense, Gormenghastly castle whose endless spaces form a many-levelled gothic universe, towering and hermetic.

The attempts to understand Griaule and the power it continues to exert, and finally to destroy it completely, forms a subtext which runs beneath all the stories. It is subjected to scientific analysis, cultural criticism and historical interpretation, but remains ultimately elusive – the unanswerable question and insoluble enigma. These studies are expressed through extracts from biographies, histories, memoirs, religious texts and art critiques, all of which make clear the multivalent impact such a manifestation of the sublime, an invasion from the fantastic other, has upon the mundane world. The actuality of this astonishing being is never in doubt. But it is something which is difficult to define and quantify. Its presence in the world pushes at and warps the boundaries of the possible, mockingly redefining humanity’s understanding of the fundamental nature of the universe. In the extraordinary opening to the 2004 story Liar’s House, Shepard writes a Genesis myth in which the dragons are held to have flown through the first fires of creation. As a result, they embody a metaphysical duality, an uneasy division of soul from body, which reflects the true nature of Creation. Their souls surround them like a cloud and affect the material body from without. Shepard concludes that ‘of all their kind, none incarnated this principle more poignantly, more spectacularly, than did the Dragon Griaule’.

Griaule becomes a mutable metaphor .The externalised soul is commonly perceived as a baleful influence exerted by the spellbound leviathan. The lives of those living in its shadow are characterised by a dour heaviness of spirit. They are afflicted by it as by a dull, background headache which won’t go away. It is thought to impose its will indirectly, guiding men and women’s actions as part of some greater plan. The ends to which it is working remain obscure, but it is assumed that they are destructive, vengeful and fuelled by hatred. It is bent on reasserting its dominance and ultimately revivifying its earthbound carcass, breaking free from the long rhythms of geological time to which it has been bound. It is a terrifying god, then, requiring constant appeasement an obeisance. Or it is a violently oppressive political force, thought vanquished and banished; a dangerous ideology driven underground but regathering its strength and coherence. Its continuation as part of the local landscape symbolises in solid form the drag of the dead, anchoring weight of the historical moment. This is a history which has been transformed over time before ossifying into a delimiting set of beliefs and assumptions. It also represents the arguments for and against the idea of free will within the human soul. And it is, above all, an inescapable genius loci, an overpowering spirit of place. A landscape which lives and breathes, and whose great, golden eyes occasionally blink open and stare blankly out from the beneath the bony overhang of its occipital brow. All of these possible aspects, these potential meanings, are explored in the Griaule stories. Indeed, they are themes Shepard has iterated in much of his fiction over the years. But here, they find their perfect, readily adaptable context.

Religions based on the fear (and secret hope for) wrathful reprisal are built up around the dragon and its mythology. Artists are inspired and consumed by the spirit of place, and those who don’t consider themselves artists feel compelled to create images of the dragon, or to collect relics associated with it. Ideologies and power bases grow up around its most significant relic in the remarkable final story, The Skull. This returns Shepard to the politicised territory of Central America which he mapped out with searing ferocity in early stories such as Salvador, Mengele and in the novel Life During Wartime. Shepard’s rootless, drifting characters, lacking moral compass or inner resolve, are the natural vessels of Griaule’s subtle manipulations. Or is it their own weakness, their inability to locate a firm centre of self or to form a solid sense of purpose, to find meaning in the world, which leads them to fall into reflexive behaviours which are then blamed on an external, demiurge force. As is often the case with Shepard’s characters, a hard-nosed, world-weary attitude prevails. Corroded romanticism, sexual obsession and a recklessness born of ennui lead to self-destruction, but also occasionally to the possibility of the salvation which is subconsciously yearned for. This may or may not be found in The Skull, which remains necessarily ambiguous. It is a political fantasy of extraordinary power and moral force. The spirit of Griaule becomes the template for all oppressive dictatorships, his dissipation into myth and the associated ideologies which the matter of myth breeds allowing for his rebirth in other forms. As Snow, the protagonist of The Skull, says about Jefe, the charismatic leader of the Temalaguan PVO (Party of Organised Violence) who is the reincarnated spirit of Griaule, ‘that prissy little fuck’s going to make Hitler seem like a day at the beach’.

In all the stories, the awe-inspiring, passively aggressive presence of Griaule is seen as an intrusion into the world, an invasion of the fantastic. This is a fantasy series in which the singular, dominant fantastic element represents control and oppressive, limiting power. As such, it is an anti-escapist fantasy, a quality it shares with M.John Harrison’s Viriconium tales. Whatever vague anti-heroism is to be found in Shepard’s Griaule stories is aimed at destroying the dragon. The erasure of the fantastic from the world, thinning its possibilities and reducing it to the mundane, is the ultimate goal. Fantasy, and the need for escape which it feeds, can be a dangerous force. It can breed monsters which grow in size and influence until they control our lives without our even being consciously aware of it. Perhaps it is significant that the dragon is finally rendered into a ruinous rubble by the power of art. We see how the obsessive, all-consuming art of the very first story, The Man Who Painted the Dragon Griaule, comes to fruition many years later. Representing the monstrous, detailing the mechanisms of its power and bringing its depredations to light can, incrementally over time, lead to its destruction. The Griaule stories are a handbook to the dispelling of damaging fantasy, to killing the dragons in the unwary mind and in the hard, unforgiving world. Their cynical surface is a necessary part of the process of dis-illusionment. What they ultimately offer is fantasy in the service of the real.

Labels:

Lucius Shepard

Monday, 25 August 2014

The Spectral Book of Horror

The Spectral Book of Horror is an instantly attractive volume. The cover is graced by a gorgeous painting by Vincent Chong showing two boys and a girl standing against a cracked and peeling wall, illuminated by a sickly yellow light. The girl clutches a standard issue creepy, porcelain-faced doll to her chest, whilst a large, bloodied knife hangs loosely from the hand of one of the boys. They wear animal, skull and Cthulhoid masks, and cast monstrous and devilish shadows, projections of their dark animas. It looks as if they are preparing to enact some ritual invocation, or are taking a break from one which is in progress. An invocation designed to raise those shadowy outlines in bodily form. Can we judge the book by this cover? To a certain extent, yes. It suggests that the terrors within will be of a largely domestic variety, and that whatever supernatural elements are present won’t be made overtly manifest. Rather they will be half-glimpsed, distorted shapes momentarily caught in the periphery of vision, or wraiths suggestively coalescing from the darkness in the farthest corner of the room. There may also be hauntings from the spectres of the intense childhood imagination which are never wholly exorcised, even if they are eclipsed by adult preoccupations. Both of these presumptions prove to be accurate.

The introduction by the collection’s editor, Mark Morris, recalls the days of the Pan, Fontana and Armada paperbacks of the 70s; a halcyon period of plenty for the short story in all the genres of the fantastic. These collections, the Pan Books of Horror Stories in particular, mixed old classics of terror and the supernatural with modern nasties, contes crueles which were sometimes little more than set-ups for gruesome fates, described with lingering relish. The Pan series was edited by Herbert van Thal, a man with a name eminently suited for the task. It looked great on the covers, and conjured an image of a Peter Cushing Van Helsing type, a smoking-jacketed connoisseur of the grim and ghoulish commenting urbanely from his walnut-panelled, book-lined study whilst drawing on an ornately curving pipe. Morris fondly summons up a childhood picture of reading torchlight under the covers on stormy winter nights, a memory which invites smiling nods of collective recognition. It envelops these anthologies in a warm, blurry haze of period nostalgia, and posits them as a strange form of comfort literature. My experience was rather different. The bleached photographic covers disturbed me, particularly the one with the half-buried head the colour of a swede, half-human, half-root vegetable. There were a couple of nasty stories which gave me bad dreams for a good many nights, and which I tried vainly to cleanse from my mind.

Morris seems to have the long-running Pan Books of Horror in mind when voices the hope that the Spectral Book of Horror may be the first in a regular series. Times have changed since van Thal churned out his increasingly tawdry selections, however. Newsagents no longer have revolving wire racks of mass-market paperbacks for people to pick up as casually as the daily paper. The market for short stories has shrunk drastically, spurious notions of value for money leading to ever-more bloated mega-novels, the increased wordage designed chiefly to expand the breadth of the spine and occupy a more prominent proportion of the display shelf. Concision is a largely lost novelistic art, and the short story is an increasingly rarefied and endangered species, protected by a few dedicated conservationists. Gene Wolfe wryly commented on the situation back in 1989 when he actually entitled his latest short story collection Endangered Species. A regular anthology from Spectral Press would by hugely welcome, then.

I think the first Spectral Book of Horror is a bit classier than the Pan books, however. Firstly, there’s that nightmarishly beautiful cover of everyday Lovecraftian terror. True, there are a few stories within which might have taken their festering place within the musty Pan covers. Anecdotal squibs like Tom Fletcher’s Slape, Michael Marshall Smith’s Stolen Kisses and the initial stages of Brian Hodge’s Cures for a Sickened World, which are essentially set-ups for gross pay-offs. All they need is an afterword from a cackling, corpse-faced crypt keeper cracking off-colour quips to complete the feel of an EC comics vignette. The other stories are far more substantial, however, with a refreshing lack of hastily scrawled tableaux of intricately agonising death (or worse). These stories are, dare I say it, more literary. They veer towards what was once defined as dark fantasy in an attempt to distinguish it from the splatter of the more visceral body horror emerging in the 1980s.

The majority of the writers are British, and the settings of their stories largely portray a determinedly de-romanticised view of the country. The stories of M.John Harrison and Robert Aickman, set in the dank, dilapidated no-spaces of unglamorous provincial towns and cities, are a touchpoint here; Harrison’s Egnaro, A Young Man’s Guide to Viriconium, The Incalling and his novel The Course of the Heart in particular. So too is the clammily creepy episode from the Amicus portmanteau film From Beyond the Grave in which Ian Bannern’s frustrated city commuter visits the drab home of ex-serviceman Donald Pleasance, from whom he has been buying matches, and meets his eerie, ghostly daughter (played by Pleasance’s actual daughter, Angela). This certainly came to my mind when reading Helen Marshall’s Funeral Rites, in which a Canadian post-grad student comes to lodge at the dingy Oxford house of the morose Mrs Moreland and her two palled, hostile nieces.

The Spectral Book of Horror is bookended by two well-known and highly respected genre writers, Ramsey Campbell and Stephen Volk. Volk’s novelette Whitstable, an affecting tribute to Peter Cushing in the form of a fictional portrait of the actor in his later years, some time after the death of his beloved wife Helen, was published by Spectral Press to great acclaim last year. There is a judicious mix of well-established writers and new voices (new to me, at least) throughout. I was particularly pleased to read something new by Lisa Tuttle, a writer familiar to me from her superb 1986 collection A Nest of Nightmares, along with subsequent novels and stories. Other familiar names include Robert Shearman (who re-introduced the Daleks to the revamped Doctor Who, and is a particularly fine exponent of the short story), Steve Rasnic Tem, Nicholas Royle (forming a connection with the early days of Interzone, and thereby indirectly with New Worlds, whose experimentalism it initially carried on), Conrad Williams, Michael Marshall Smith and Stephen Laws. But newer or less established writers provide material of equal power and accomplishment here. The Spectral Book of Horror serves a vital (and increasingly rare) function in this respect, providing new stories from familiar names, which will attract the attention of the discerning genre reader, whilst also building a nurturing environment in which a fresh generation of talent can be fostered.

Ramsey Campbell’s story On The Tour opens the collection and to a great extent sets the tone. Its portrait of Stu Stewart, former drummer of Merseybeat also-rans The Scousers, finds Campbell back on home, Liverpudlian territory. Stewart’s is a life eked out on the thin, dusty sustenance of worn and threadbare dreams, confined within the grooves of the record stacked amongst the seldom-browsed LPs of Vin’s Vintage Vinyl, the shop where he works. The mirthless humour of the exchanges he has with his boss Vin, dialogue underscored by indirect power play, together with the sense of a life staged as an increasingly desperate performance for an imaginary audience (the rock nostalgia tour bus which purportedly includes his house on its programmed route) puts this in the absurdist territory of Pinter and Beckett. The horror here is of mental breakdown, of sustaining illusions being dispelled. We are caught unsparingly within the subjective viewpoint of a life and a mind unravelling, following Stu’s steadily accelerating descent. The ironic juxtaposition of this narrative perspective with our comprehension of its increasing illogic and delusory disconnection from the real is reminiscent of the psychological sketches of the inner life Katherine Mansfield drew in her short stories. Campbell’s subtle direction of events towards a point where they go very badly out of control is what pushes this in the realm of horror, although the terrain is not established with any obvious generic markers. The suggestive final paragraph is a classic case of allowing the reader’s imagination to fill in detail, creating manifold horrors from the shadowy substance of their own fears.

Further excursions into the absurd can be found in John Llewellyn Probert’s The Life Inspector, in which the right to continued existence is weighed up according to the hermetic illogic of a relentless and briskly efficient bureaucrat. Nicholas Royle’s This Video Does Not Exist is a self-interrogating story, pitching a surrealist piece of absurdism involving a man who wakes up to find his head is no longer visible in any reflections against real world horrors read about in the papers and seen online and in the news in which people genuinely lose their heads. National and international events mirror each other, and the whole world seems to have descended into absurd drama, staged for a ready audience plugged into diverse media. In the face of this new, terrifying reality in which globalised, digital technology goes hand in hand with barbarous savagery, the main character’s personal crisis of identity comes to seem like an indulgence, and the story ends abruptly with his inner narrative being abandoned. The existential headless man scenario might be seen as typical of Royle’s thematic and stylistic territory, and as such there’s an element of auto-criticism here. I can imagine the story’s initial conceit being inspired by a Magritte painting, just as his novel Saxophone Dreams was inspired by the surrealist paintings of Paul Delvaux. Indeed, Magritte’s painting La Reproduction Interdite (Not to be Reproduced), depicting a man looking in a mirror which reflects the perspective we see of the back of his head, is described in the story, suggesting a probable point of inspiration. It was also used in the 1974 film Un Homme Que Dort (A Man Asleep), based on a short novel by absurdist writer Georges Perec, who also worked on the adaptation. This tale of existential drift and disappearance in Paris has definite affinities with Royle’s work (as well as dovetailing with his cinephile side), and I wouldn’t be surprised if he was familiar with it.

Magritte - La Reproduction InterditeOne of the pleasures of an anthology which has no explicit linking theme or subject lies in creating your own connections. Certain similarities or correspondences reveal themselves, and conspicuous differences in style and approach also become apparent. The subjective realism which Campbell establishes is further explored by a number of writers here. The fear of aging, and the attendant sense of life’s possibilities diminishing - of watching your life slide out of view, as Jarvis Cocker put it – is present in Michael Marshall Smith’s Stolen Kisses, Angela Slatter’s The October Widow, Conrad Williams’ The Devil’s Interval, Nicholas Royle’s This Video Does Not Exist and Steve Rasnic Tem’s The Night Doctor. A number of stories also feature lonely characters who are disconnected from society, for whom the prospect of mental disintegration is an everpresent and very real terror. Nora Higgins, the socially withdrawn protagonist of Helen Marshall’s Funeral Rites, conspires in her own fate, almost welcoming the oblivion of its cold embrace. Cecil Davis, in Angela Slatter’s The October Widow, is an aging, isolated character leading an enervated, bare bones life dedicated with van Helsing purity of purpose to the pursuit of a Pagan seasonal spirit, one of whose sacrificial victims was his son. The central relationship of the protagonist of Conrad Williams’ The Devil’s Interval, an aimless office drifter, is with his guitar, which becomes a dangerously uncontrolled channel for his suppressed emotions and banked up anger. And Ramsey Campbell’s Stu Stewart, trapped in a moment of eternally recycled nostalgia, is another aging loner cut adrift from the here and now.

Family life is another common thread, but few comforts are offered to counterbalance the hollow loneliness and mentally fraying isolation found elsewhere. Instead, it is shown at its most claustrophobic and controlling, swallowing up and absorbing individual identity and endeavour. This is the family of knotty Freudian entanglements, the unspoken subterranean roots dug up and exposed to the withering light. In Gary McMahon’s Dull Fire, the couple tentatively beginning a relationship carry the ghosts of their abusive mother and father with them on their rootless travels. The story contains a sentence which encompasses the generally downbeat tone of the collection, a Philip Marlowe-esque observation that a rundown hotel room is ‘the kind of place lonely suicides might come to end their miserable days’. It is, instead, the place where the protagonists try to start something which will ease their loneliness and misery. Robert Shearman’s Carry Within Some Sliver of Me (a poetic title with echoes of Ray Bradbury and Harlan Ellison) is full-on Freudian horror, describing a monstrous, devouring mother with repulsive literalness. As with McMahon’s story (with its equally monstrous father), the fear (or dull acceptance) of inheritance, of growing into the monstrous parent, is foremost. Monstrous fathers also turn up in Rio Youers’ Outside Heavenly and (to a lesser extent) Stephen Volks’ Newspaper Heart, while Helen Marshall’s Funeral Rites has a monstrous mother-in-law by proxy.

South coast modernism - the De La Warr Pavilion, BexhillAlison Moore’s Eastmouth is about being absorbed into someone else’s close-knit family, and the anxiety of the isolated individual over loss of self-identity. The protagonist, Sonia, sees her dreams of a showbiz life wither and fade, reduced to the antediluvian end of the pier attractions of a southern seaside town caught forever in a mid-century stasis. The description of a ‘modernist pre-war building’ suggests that Moore may have had Bexhill in mind. The amazing De la Warr Pavillion, built on the seafront in 1935, is one of England’s finest buildings in the modernist International Style. It’s actually been recently restored to its former glory in a 2005 refurbishment and hosts a fine programme of art exhibitions and concerts. But I know what Moore has in mind – the tattered, dilapidated remains of pre-war utopian dreams. The story contains a sentence which perhaps contains the purest distillation of horror in the whole collection, when the man whom Sonia seems fated to marry boldly declares that Cannon and Ball, who are appearing at the theatre, are his favourite act of all time. She should have run screaming at that point. Moore’s evocation of out of season melancholy and grubby memories of childhood excursions to the seaside exemplify the seedy scenarios of a good many of the stories in the collection. It’s a place where ‘nothing changes’, where you are stared at by ‘dead-eyed gulls’ and the front is weakly illuminated by ‘sunlight the colour of weak urine’. An entropic environment redolent of personal and national inertia and decay. The view of the family as an oppressive, constraining force is here extended to the whole town; a closed community monomind, just a few shambling steps away from agglomerating to become a gesticulating zombie horde. There’s something a little reminiscent of an English variant on Shirley Jackson’s classic short story The Lottery here.

Ironically, the only positive take on the family as a supportive, encouraging unit is offered in Stephen Laws’ Slista; and the family here is monstrous, murderous and possibly not even human. Alison Littlewood’s story The Dog’s Home plays on the reluctant obligations and financial wheedling attendant upon relations with more indirect, spiky branches of the family tree. It’s also one of a number of stories whose first person narrative voice gives a misleading initial impression of balance and reason. Scary Aunt Rose is the dragon of the family, whose thorny harshness is tolerated and indulged in the hope of charming or inheriting a share of her hoarded wealth from her. Her hardness in the face of the family’s penury is contrasted with the unconditional love and loyalty of her dog. This dog becomes the emotional focus in a tale of betrayal and cruelty. Again, it is madness, the loss of rational control, which is seen as the ultimate horror here.

The family stories culminate in Stephen Volk’s Newspaper Heart, the Spectral Book of Horror’s final tale, a powerful piece firmly rooted in a specific time and place (October 1970 in the Welsh Valleys). As he did in his intense scripts for the Afterlife series, Volk unearths the fears inherent in family life, bringing them to life and examining them unflinchingly but with great compassion and empathy. The story is partly a variant on the creepy ventriloquist’s dummy tale, the dummy in this case being a baby-faced bonfire night guy rather than a tux-clad wooden-head with fixed grin and ruddy cheeks. It’s also a descendant of the old changeling folk tales, an acknowledgement of the ancient roots of late October and early November fire festivals. The horror elements here are a way of exploring any number of emotional and psychological subcurrents within the family. Parental anxiety over the child’s safety; the effect of economic depression on a marriage, and of marital drift on a child’s mental stability; the slowly corrosive effects of class-selfconsciousness and division; the thin boundaries between childhood and adulthood, with the marital home compared with the school playground; and a mother’s guilt at the unutterable suspicion that they might not love their child as much as they’re supposed to – or even that they might wish that they’d never had them. The familiar litany of period TV favourites are intoned (Blue Peter with Val, John and Peter, the Vision On gallery music), along with the more conservative end of the pop spectrum (Elvis, Mary Hopkins and Smokey Robinson). But rather than a prompt for nostalgia, these are used more to suggest stultifying routine and narrow limitations. This counter-nostalgia is re-enforced by the simultaneous citation of news stories about Vietnam, Biafra and Northern Ireland. The mention of the Mexico 70 World Cup also summons up retrospective feelings of disappointment, an ‘end of the 60s’ come down. Newspaper Heart demonstrates just how multi-layered and complex the short story form can be, with a dense pattern of allusion, metaphor and symbolism combining to crate potently suggestive and multivalent meanings. Importantly for a horror story, it’s also very scary, with a few of those moments of chill frisson which masters of the supernatural expertly engender. This is undoubtedly one of the highlights of the collection, and I can see why it was chosen as the closing story.

Two authors provide variations on the theme of the performer becoming confused with their signature stage or screen role, either in their own minds or that of their fans. Brian Hodge’s Cures for a Sickened World is a third story of warped and delusory rock dreaming, of the spurious power which its self-mythologisation confers, to add to Ramsey Campbell’s On the Tour and Conrad Williams’ The Devil’s Interval. It begins as a sick revenge on the critic tale, with a snide, destructively negative online reviewer’s hyperbolic figures of speech, used comparatively to delineate what he’d prefer to do rather than listen to the music of a costumed shock metal band called Balrog, taken at face value by its lead singer, Ghast (aka Tomas Lundvall). Cue Saw-like punishments designed s morally corrective lessons. The story develops beyond such limited, mechanical parameters, however, going on to explore notions of moral culpability, the relative nature of evil, the delicate balance between a performer’s stage persona and his or her real self, and the corrupting effect of the urge to use shock-tactics to gain attention in a media-saturated world.

The disjuncture between real and media selves is also the subject of Lisa Tuttle’s alliteratively titled Something Sinister in Sunlight. It features an English actor, Anson, who has become shackled to the role of a serial killer called Cassius Crittender, a character who has become increasingly charismatic as his popularity flourishes, gradually completing the transformation from cold-blooded psychopath to agonised romantic. It’s a moral metamorphosis which many fictional monsters undergo as they become familiar to the point of becoming de-fanged and -clawed. Now it’s the turn of the mythologised serial killer, that very modern monster, to be romanticised, as we have seen in the later Hannibal films and the TV series Dexter; the good serial killer thwarting the bad. Tuttle’s story plays upon this romanticisation and all that it implies – the old connection between sex and death familiar from Freud and French decadent writers and poets. The fact that Cassius’ attraction is mainly felt by women whereas Anson is gay adds another level of play-acting complication between performer, role and obsessive viewer. When Anson accepts an invitation to dinner at a female fan’s house, the tensions which these layers of illusion create come to the surface, with alarming results. Tuttle’s stranding of an English actor in LA in this role is a wry comment on the way that British stage gravitas translates into villainy in Hollywood. There’s another allusion to the weakness of the English sun. But whilst it was a symbol of provincial dullness in Alison Moore’s story Eastmouth, a dim spot from which the main character dreamed of escaping, heading for the bright lights of America, for Anson the opposite is the case. He yearns to return home to his partner, to fly away from limiting fame and from the bleached out light of California to get back to the grey, rain-heavy skies of Blighty. It’s a neat reversal of the more common location of Hollywood as the locus of dreams of escape.

Two stories make play with language to create narrative perspectives removed from the norm. The first person narrative of The Slista by Stephen Laws is written in a phonetic language whose stunted words suggest a devolved version of our world. The basement dwelling family hints at first at a post-apocalyptic scenario, with the simplified spelling similar to that in Russell Hoban’s novel Riddley Walker. But is soon becomes apparent that whoever is speaking in this strange, slurred tongue is part of a group of shadowy wainscot dwellers looking out on the contemporary world from the spaces in between. The Book and the Ring by Reggie Oliver is written in formal Elizabethan English, the language conveying historical antiquity with first person immediacy. It reminded me of the 16th century narrative of David I Masson’s 1965 tale A Two Timer, first published in New Worlds. The Book and the Ring is an M.R.Jamesian tale of ancient books uncovered during scholastic researches in ecclesiastical surrounds which bring to light strange and troubling stories of long-buried occult encounters. The devil which is summoned by the Elizabethan composer Jeremiah Starcky from the usual tome of dangerous lore acquired from a local witch takes the standard passive aggressive Satanic approach of giving human greed, lust and attendant paranoia space to fashion their own irrevocable damnation. It’s a tale told with great gusto, taking particular delight in period cursing and swearing. With its full panoply of witches, devils, books of the damned and souls in mortal supernatural peril, this is one of the most purely pleasurable stories in the collection.

Oliver’s story is atypical in its traditionalism. The Spectral Book of Horror withholds many of the traditional pleasures of the genre. The classic gothic bestiary is extinct here, perhaps because it currently thrives in terrain purists disdain. There are few manifestations of the supernatural or intrusions of the exobiological (ghosts and monsters). And what devils do appear are at least partly demons of the mind. The writers mine the dark caverns of the human spirit for their fears and terrors. Newborn monsters are present at the edges of some tales, however. The torturous, vampiric relationship between rock star and journalistic parasite in Cures for a Sickened World gives birth to a new breed of demon, waiting in the shadows to be fully defined by human appetites. And the title creature of Steve Rasnic Tem’s The Night Doctor is a spectral figure with an inhuman, faceless head and a dark, leathery bag who appears when you are sleeping to offer dubious cures which may ultimately be worse than the illness itself. It’s an embodiment of fears of aging, physical decline and death, either of oneself or of those one loves.

Older forces are summoned up in Angela Slatter’s The October Widow and Rio Youers’ Outside Heavenly. Slatter’s tale is a piece of modern Pagan horror, bringing sesasonal sacrifices into the contemporary world. Inevitably, there are some echoes of The Wicker Man here. Very faint ones, though, perhaps more from its endless citation as a point of comparison. Outside Heavenly is a piece of Midwestern gothic which also incorporates elements of the police procedural. Police Chief John Peck is an inadvertent occult cop, as opposed to the more traditional occult detectives such as Algernon Blackwood’s John Silence and William Hope Hodgson’s Thomas Carnacki. Demonic energies have destroyed a monstrous father with grim thoroughness. The devil here is a wish fulfilling avenger, but one which also represents the psychological (or even spiritual) damage the abused offspring inherits from the abuser, even (or especially) after they are caught and punished. It’s to Youers’ credit that he doesn’t pander to the easy release of the revenge fantasy here. The evidence which the Police Chief eventually uncovers is akin to the folktales of Lucifer over Lancashire – burning hoofprints left in a huge striding trail across the landscape.

This is a fine start for the Spectral Book of Horror. The stories tend towards the darker end of the spectrum, and the moral certainties of older gothic horror forms have totally disappeared. It makes for an uneasy read at times, perhaps even connecting with personal anxieties to disconcerting effect. This is not horror as escapist fantasy, but horror facing the fears and uncertainties of the modern age, and of the modern, embattled psyche. By thus confronting them, we can go some way towards dispelling, or at least controlling them. Let us hope that Mark Morris’ and Spectral’s plans for further volumes come to fruition, and that we are offered further caustic, homeopathic balms for our unconscious terrors.

Labels:

Lisa Tuttle,

Nicholas Royle,

Spectral Press,

Stephen Volk

Tuesday, 12 August 2014

Ben and Winifred Nicholson: Art and Life 1920-1931 at Ways With Words, Dartington.

Jovan Nicholson gave a talk about his grandparents Winifred and Ben Nicholson as part of the Dartington Ways With Words Festival in July this year. He has curated an exhibition of their work, Art and Life 1920-1931, which is currently on display at the Dulwich Pictuer Gallery in London. The show also incorporates three other artists with whom the Nicholsons were close in the 1920s and early 30s: Christopher Wood, Alfred Wallis and William State Murray. Nicholson was particularly enthusiastic about his inclusion of the latter. He hopes that this renewed exposure will go some way towards reviving the reputation of a potter whom he feels was one of the finest exponents of the art in Britain in the twentieth century, quite the equal of his contemporary Bernard Leach.

Ben and Winifred Nicholson in 1923Nicholson’s approach to his subjects in the exhibition and the accompanying book is a comparitive one, and this was the approach he took in the talk as well. He set particular works alongside each other, and thereby illustrated ho the artists influenced and inspired one another. They sometimes painted or drew the same landscapes in their own individual manner, initial similarities gradually diverging significantly as they established their signature styles and outlooks. Ben’s pencil sketch and Winifred’s watercolour of a rural hillside scene at Tippacott in Devon, where they went in 1920 just before their marriage (in fact, they got engaged during this trip), show a congruent, straightforwardly representational approach to the view. Trees, hedgerows and hillcrest contours are all present and relatively proportional in both pictures. At this formative point in their artistic development, their way of seeing the world was largely convergent. Later, and speaking in a broadly general sense. Jovan outlined the way in which their work would diverge: Winifred would concentrate more on colour, and Ben on form.

Winifred found her metier early on, painting some of her first threshold flowers in 1921, the painting Polyanthus and Cineraria being a good example. Its bright contrasts pointed to her future explorations of colour combinations, whilst the undulant brushstroke of blues above the brown flowers on the left side of the vase anticipates in abbreviated form the exuberant, canvas wide waves of her 1928 St Ives painting Boat on a Stormy Sea. Jovan drew attention to the metaphysical and symbolic elements of Winifred’s principal subject matter. The division between domestic interior and exterior landscape, with the nurtured blend of floral colours (and the stable forms of the vases, jugs or glasses from which they emerge) placed in between, represent the conscious act of seeing, of intense, aware vision.

Winifred's Chelsea roofscape on the cover of Christopher Andreae's bookBen took longer to explore and develop his feel for austere, simplified form, which eventually led him towards total abstraction. An early abstract painting from 1924 was shown here, but it was a tentative experiment which didn’t immediately lead anywhere. It was held back and worked on over a long period of time. It derived from a collage, and the ragged edges and superimposed rectilinear shapes were faithfully reproduced; in its own way, a piece of representational art. Jovan’s comparison with Winifred’s window-framed 1925 roofscape, Kings Road, Chelsea, painted from the same Chelsea studio in which this work was created, led you to see a similar arrangement of chimneys, brickwork, sloping roofs and squares of sky in Ben’s abstract.

Slides were shown in carefully chosen pairs, projected onto the white plaster wall of Dartington Hall, above the large mouth of the fireplace. This provided an interesting and generally highly appropriate additional element of medieval texture. Ben Nicholson’s 1925 still life Jamaique was shown alongside Winifred’s Flowers in a Glass Jar from the same year. It amply served to demonstrate how far they had diverged in their approaches by this point. But Jovan pointed out the clear correlation between the pink pentagonal base on which Ben set his flattened objects and the pink which Winifred used for the principal flowers in her composition. William Staite Murray’s elegantly shaped bowls, pots and vases with their boldly imaginative patterning and painted designs, and the unconventionally shaped boards which Alfred Wallis used, which often guided the compositional form of his paintings, were shown to have inspired Ben to be daring and intuitive in his own explorations of form. His instinct towards reduction, a preference for simplicity and a stripping away of extraneous detail, was encouraged by his exposure to Wallis’ work. The extent to which he began following through on this instinct was seen in the two drawings of the same Cumberland landscape made by Ben and Christopher Wood on a sketching trip they made together in 1928. Wood’s depiction of the scene is full, depicting all the elements he saw before him: outlined trees, a farmhouse, a river, a shaded hillside horizon line and a chimney smoke haze. It pointed to a richly detailed landscape which might later be produced. Ben, on the other hand, leaves wide expanses of empty space, with a few boldly outlined trees scattered singly or in tight clusters and the outline of the River Irthing sharply curving across the flattened foreground. The horizon is marked by a single lollipop-shaped tree, a darkly shaded marker beacon. The farmhouse has completely vanished, surplus to compositional requirements. Ben was now transforming what he saw to conform with his own rigorous artistic vision.

Jake and Kate on the Isle of Wight - Winifred NicholsonJovan talked about the work rather than the lives of his grandparents. Personal touches did come through, however. He confessed that he found it almost impossible to rad the recriminating letters they wrote to each other when the marriage was falling apart in the early 30s. Winifred’s 1931-2 painting Jake and Kate on the Isle of Wight, depicting two of their three children sitting at the table of the house she had rented at Fishbourne for the winter, dates from the period of their separation, after Ben had gone to live with Barbara Hepworth. Jake and Kate wear party hats, which suggests it might be Christmas. But as Jovan pointed out, they look bewildered and lost rather than excited. The disjuncture between the light colours and carnival hats and the children’s sombre faces is very poignant. Jovan evidently felt an empathetic connection with them as he described their expressions. ‘The one on the left is my father’ he added, almost incidentally.

He also showed his steel when a questioner at the end implied that there might have been an element of exploitation in Ben’s relationship with Alfred Wallis, and that he made a healthy profit from selling his paintings on to London dealers. Jovan took a deep breath before replying, paused significantly and acidly thanked the person in question for giving him the opportunity to put such myths to rest, which he proceeded to do with thoroughness and conviction. His grandfather’s honour was vigorously defended, and Wallis depicted as a sharp, highly self-aware individual. Not the sort to allow themselves to be exploited by anyone. He firmly stated that he had found no evidence of Ben ever selling any of the Wallis paintings that he had bought. Rather, he donated a good many to a wide variety of galleries and museums. This, together with his tireless promotion of Wallis’ work, raised (and indeed initially created) Wallis’ profile in the eyes of the metropolitan art world, and brought people to his door in St Ives, generating many commissions. For this, he was vocally grateful, and Jovan told us that he loved the attention which he received as a result.

He also countered the general perception that Ben could be doctrinaire and hardline in his promulgation of the artistic school of thought he happened to favour, his work ascetic and forbidding as a result. He emphasised the humour he found in his work. The trompe l’oeil play with perspective in his 1925 Still Life With Jug, Mugs, Cup and Goblet, for example, the white goblet on the left being simultaneously in front of and behind the adjacent slate grey vase. His animals display a certain childlike delight, too. Jovan found this sense of ‘fun’ in Wallis’ work, as well. The parallel array of pyramidal sails and icebergs in Schooner and Icebergs (1928) was highlighted as an example of Wallis’ lightness and humour.

Poster for the Kettle's Yard showing of Art and Life, with Ben Nicholson's JamaiqueHe was also fulsome in his praise for Jim Ede, the former Tate Gallery curator who set up home in four converted cottages in Kettles Yard, Cambridge in the 50s. He was also a long-term supporter of Wallis, and of Ben and Winifred. Kettles Yard housed a good number of their works which he had bought for his own collection. It still does to this day, as a wonderfully atmospheric house and gallery, the paintings and drawings taking their place amongst aesthetically arranged domestic objects and fittings (Wallises in the bathroom, Nicholsons above the bed). His use of the familiar diminutive ‘Kit’ when referring to Christopher Wood suggested a feeling of personal connection here, too.

Wood’s ravishingly sensual portrait of the aristocratic Russian émigré Frosca Munster, The Blue Necklace (1928) paints a picture of an emotionally complex man, as Jovan explained. Letters between the two, and from Winifred to Frosca, made the depths of Kit’s feeling for her plain. Her departure from Cornwall, and the British Isles, was almost certainly precipitated by her becoming pregnant by him, and he was left bereft by her sudden absence from his life. His primarily gay sexuality was frankly expressed in the 1930 interior Nude Boy in a Bedroom, which Jovan also showed us. It has a casual, relaxed sense of intimacy, with the subject half-turned away from our (and the artist’s) view as he dries himself with a towel. Picture cards are scattered on the bed as if they’d just been studied (the boy is looking at another small reproduction on the wall) and the shutters are half closed, letting in light whilst maintaining a sense of a private domestic world.

Christopher Wood - Zebra and ParachuteJovan showed us the last painting Wood finished before his suicide in 1930, Zebra and Parachute. The stark, white lines and masses of the modernist architecture in front of which the passive body of the zebra is posed have echoes of the white reliefs which Ben would produce in the mid-30s. They also anticipate Berthold Lubetkin’s introduction of European International Style modernism to London Zoo (and England) in 1933-4 via the gorilla house and penguin pool he designed for Tecton. But the hanged man limply suspended beneath the bright colours of the parachute in the background, along with the incongruously exotic creature in the foreground, hint at a possible turn towards surrealism belying the ascetic modernist backdrop. This would certainly have put him at artistic odds with Ben, widening the personal rift which his heavy use of opium had already opened up.

The period whose end was so tragically and drastically underlined by Wood’s death, and soon after by the break up of the Nicholsons’ marriage, saw the group of friends and compatriots who had been so close in the 1920s drift apart both personally and in terms of artistic style and intent. But during that intense decade during which they shared each other’s thoughts, homes and paints, they left a lasting mark on each other which continued to make itself felt in their work. The 20s were the years in which the seeds were sown, and the enriching cross-fertilisation took place. Jovan Nicholson’s talk, his book and the exhibition which he has curated ably and definitively traces the streams of influence and inspiration which flowed between them, and which kept them invisibly connected throughout their lives, no matter how far their outlook diverged, or how strongly their opinions were expressed. Some things just can’t be broken.

Friday, 1 August 2014

Theo Brown and the Folklore of Dartmoor - Devon Folklore Tapes Live at the Phoenix, Exeter

The Devon Folklore Tapes VI release Theo Brown and the Folklore of Dartmoor was brought to life in the Phoenix, Exeter last week, not far away from the terrain from which it drew visual, aural and even biological material. The sounds on the DVD, CD, vinyl singles or cassette (the Folklore Tapes folk are catholic in their use of media) are often ambiguous, both spatially and in terms of identifiable sources. The prospect of discovering how they went about building this soundscape, which invokes both the Dartmoor environment and the haunted spectres, legendary beasts and fey creatures which are conjured from it, and how they would go about projecting it into a small hall rather than a living room or headphone-space was an intriguing and enticing one.

N.Racker - with cover image taken from Juraj Herz's 1969 film The CrematorFirst up was N.Racker, aka Sam McLoughlin of Sam and the Plants renown, an old Folklore Tapes compatriot. I’d previously come across him at the late lamented LLAMA (Lynton and Lynmouth Arts and Music Association) festival, where he was utterly absorbed in striking coiled springs suspended from the frame of the small marquee tent which canopied his antediluvian electronic equipment. There seemed to be a good deal of wooded casing, and it looked as if it might have been salvaged from a WW2 radio communications HQ in the post-war period. This produced a pleasing visual analogue to the springy, metallically glinting radiophonic sounds he coaxed from his hands-on box of tricks. It was music for crackling campfires or starlit summer skies streaked with the occasional meteorite trail.

Tonight, he explored darker realms, and kept the lights down low. He sat in the midst of a modest array of small synths, electronic circuitry and home-made or modified instrumentation, lit only by the green glow which casts its heart of the oakwood radiance through a hexagonal box (a defunct bass drum?) at the front of which a dessicated frond of bracken was silhouetted. Sam scraped and struck and plucked whatever came to hand: zithers, lyres whose strings were metallic rods embedded in a length of wood (Les Sculptures Sonores and Harry Bertoia came to mind here), and an electric hand fan whose blades served as whirling, whirring plectrums. Everything seemed to be mic’d, so an object dropped to the ground produced a clangourous thump. This could then be looped and incorporated into the organically expanding soundmass.

There was a definite improvisatory, aleatoric feel to the proceedings, with chance and accident welcomed as cues and ideas for intuitively exploring new directions. The vaguely ominous ambience suggested supernatural scenarios, with synth lines brewing up John Carpenteresque Fogs. Sam even essayed the dextrous Rick Wakeman stunt of playing two instruments simultaneously, arms bridging the right-angled span between keyboards (or synth and zither in this case). Conspicuous virtuosity was not at issue here, however. The instrument banks were many degrees smaller than Wakeman’s monumental podium-mounted edifices, and far from requiring their own articulated lorry to transport them, could probably comfortably fit in a hatchback boot. Besides, Sam wore a self-effacing white t-shirt rather than a glittering cape, making his lack of interest in such showmanship quite plain. This was more a question of contrasting textures, the plucked string electro-acoustically transformed and the synthesised sine-wave.

The music came to the end of its natural lifespan, expiring after Sam had looked around for the next object to pick up and decided that, no, he had nothing further to add. He modestly suggested that we could repair to the bar now if we wanted, while he embarked upon a further sonic expedition. Perhaps it was a friendly warning. Because he proceeded to unleash a howling jungle of sound from his synth, harsh hissing, stridulent screeching and squelchy croaking. Several people did indeed decided it was time to refresh their glasses. I found it an exhilarating storm of noise, however. It reminded me of Henning Christiansen’s Symphony Natura, which I heard as part of the At the Moment of Being Heard sound art exhibition in the South London Gallery in Peckham last year, and whose sounds were recorded in Rome Zoo. It also brought to mind Bernard Parmegiani’s De Natura Sonorum and Pauline Oliveros’ early 1967 electronic piece Alien Bog. The latter is a marvellous title which could equally have lent itself to this unleashing of the untamed forces at the wilder edges of the synth spectrum.

David Chatton-Barker and Ian Humberstone commune with the spirits of DartmoorThe two artists behind Devon Folklore Tapes VI (and the whole Folklore Tapes project), David Chatton-Barker and Ian Humberstone, came on to introduce their performance. Besides being musicians and sound artists, Barker is a visual artist and graphic designer and Humberstone a writer and librarian. These professions and talents combined in the first half of their programme, as words and images were harmoniously combined. They told us of the life and remarkable work of the folklorist Theo Brown, who was herself a talented visual artist. Photographic portraits and examples of her striking, dramatic woodcuts were shown on a small screen to the right of the stage. After this eulogy, they took it in turns to read out a selection of the tales which Theo told. We heard of the Sow of Merripit and its pitiful plaint; of the siren call of Jan Coo and the dangerously capricious moods of the Piskies; of the demonic invasion of the church at Widecombe-in-the-Moor by hovering and prowling ball lightning; the hunting down and eradication of the last wolves in the Dartmoor forests; the grimly humorous anecdote about the death of the Warren House Inn publican and winter preservation techniques in the remote heartland of the moor; and of the sad isolation of Dolly Copplestone in her lonely moorland stone cottage. All of these legends were told in David and Ian’s soft, mellifluous Mancunian and Edinburgian tones, which gave them a storyteller’s distance from their source. There was a delightful air of Jackanory about the whole thing. A zither provided the odd emphatic flourish, underlying a dramatic moment or bringing things to a conclusion, as if turning a page or firmly closing a cover. It was a touch which made a connection with older oral storytelling performance traditions; traditions superbly brought to life by Benjamin Bagby in his wonderfully atmospheric telling of the Beowulf tales, his cradled lyre providing the dramatic musical interjections.

The young TheoThe reading were lent an accompanying visual poetry by projections cast onto an adjacent screen. Whoever had ceded the storyteller’s chair crouched down over an Overhead Projector laid on the floor to the rear of the stage and sifted through a jumble of transparencies. These were slid onto the illuminated table and the sometimes rapid progression of images making their momentary appearance on the screen gave an impression of basic yet evocative and effective animation. They offered prompts for the imagination. It was somewhat reminiscent of the Eastern and Central European animations of the mid 20th century, with their cut-outs and silhouettes. This was the kind of hands-on device (and hands were indeed visible on the screen from time to time) which the duo favour. An OHP is an old-fashioned and readily graspable mechanical apparatus which you can manipulate and tinker with, a more personal level of technology than that which we are confronted with in every aspect of life today. One noticeable advantage of using an OHP rather than some modern digital affair is the absence of the lengthy prelude during which a procession of people try to figure out just how you magic your meticulously prepared and catalogued laptop pictures onto the projector screen. Here we’re back to the old days of simply pressing the on switch. There was a certain element of randomness and the chance moment to the rough order from which images were selected; an openness to the happy accident similar to the musical approach taken by Sam in the first half.

Simple means were ingeniously employed to create OHP special effects. A semi-opaque circle within a black square of masking card framed a picture of the Widecombe-in-the-Moor church tower, enveloping it in a sulphurous brimstone haze. Moorland matter – leaves and twigs and bracken – was scattered onto landscape photos to produce branching, brachiate silhouettes which invoked the Matter of the Moor. Red sweetwrapper cellophane smoothed out over the Warren House Inn sign cast it in a hellish glow. Dark inkdrops splashed onto a woodcut of a wolf were smeared out to reveal their blood red pigmentation. It could almost have been an homage to the ominously portentous opening scenes of Nicolas Roeg’s film Don’t Look Now, in which Donald Sutherland’s characters spills something on a slide of a church he is studying, causing a red stain to spread across it like an expanding pool of blood. It was a very effective moment. There was something inherently refreshing and involving in watching the performers busily sorting through and playing with the images in the background. The process was made transparent. It re-connected us with the materiality of art, with the palpable feel for the way in which images are created. There seemed to be a deliberate rejection of the kind of digital sophistication which can remove us from any sense of human agency or individual artistic signature. Long the defiantly Luddite amateur, the inspired tinkerer, their actions silently cried.

Such an ehos was carried through into the second half, when they picked up their instruments, and were joined by Sam, who returned to the stage. This trio provided a soundtrack to the super 8 film they had made on their travels through the Dartmoor landscapes and villages. The film itself veered towards flickering ochre abstraction, its bracken, heather and granite colours partly the result of the biochemical processes of decay caused by its burial for a period in soil and organic matter brought back from the moor .The film material itself embodied time and erosion. As images of tors, ponies and rivers, churches, bridges and inns manifested from the kinetic play of transformative colour and nebulous form, memory (personal and cultural) and the elusive spirit of place was poetically evoked. The music incorporate field recordings, along with effects-blurred guitars, bowed objects, electroacoustic zithers and home-made instruments and electronic wizardry and gimcrack inventions of diverse and mysterious variety.

It formed a continuous, evolving suite, with moods shifting from the haunted and sinister through the devilishly playful to the plaintive and melancholy. Hints of Radiophonic soundtracks to supernatural children’s TV series came through – think the Moon Stallion and The Changes (out this month on DVD!!) There was a touch of spacy dub to the Widecombe section, tracking the floating balls of lightning across the pews, and a Ghost Boxy ambience to some of the more melodic passages. There was also a good deal of abstract soundscaping, which suited the constant transformations hypnotically flickering and flaming across the screen. It was a highly effective translation of the atmosphere of the DFTVI recordings into a live context. For a short period of time, the spirit of Dartmoor’s landscape was raised in the Phoenix. And who knows, a part of it may remain there still.

Labels:

Devon Folklore Tapes,

N.Racker,

Sam and the Plants

The Re Interpretation Exhibition at St Olave's Church, Exeter

Six artists occupied St Olave’s church at the to p of Fore Street, Exeter last week for a short residency organised through the auspices of the Methodist Venture X project. St Olaf himself was a far from peaceful man, being a fairly typical Viking chief and king. He is depicted atop the altarpiece with two-headed axe firmly grasped in his fists, with evident intent to use it. This temporary artistic invasion was a wholly benevolent one, however. The artists questioned the role of religion in the modern world, certainly, but there was no crude iconoclasm or cheap attempts at blasphemous shock on display. This was, rather, a genuine and generous response to a sacred space hidden within the busy, noisy heart of one of the city’s prime drinking and clubbing zones, and to the sense of continuity which the building’s cenuries-old presence provides.

You brushed against art immediately you passed through the arched entrance. Judy Harrington had strung a kind of bead curtain across the doorway. But instead of beads, she had threaded together plastic strips of pill packaging. This was a foretaste of her pill crosses, which were suspended around the altar screen inside. These embedded medication and its packaging within translucent Perspex crosses. There was a simple aesthetic dimension to the objects. They caught the light streaming through the windows, and the colours, shapes and patterns of the carefully arranged pills were visually very pleasing. They resembled inlaid gems and jewels, the foil packaging beaten silver panels. There was a significant symbolic element too, of course, as there would be with any re-interpretation of the central symbol of the Christian faith. Her plastic crosses reflected, with some irony, the crosses and crucifixes which are a permanent fixture of the church. Judy’s crosses are also objects which symbolise suffering, offering salvation through chemical relief from physical pain rather than the spiritual solace offered by the Christian cross.

Judy also created the photographic tryptych Falling, which was propped beneath the gaily decorated pipes of the small church organ, and above its stops, keys and pedals – a place between. Each photo depicted the same pair of white feathered wings, but the quality degraded as they progressed from left to right. It was if the camera had witnessed the process of decay over a long period of time. An awareness of fragility, both of body and spirit, inhabits the photos. By placing them within brick gothic arches, Judy locates this knowledge of mortality and impermanence – of the Fall – at the heart of the structure of religious belief. The wings, like the crosses, resonated with objects in the church; with the statues and relief carvings of angels and memorial cherubs. They also represent the flight of the spirit or the soul, and its gradual encumbrance with the weight of time and wounding experience. Their location beneath the organ pipes conjured currents of air, and the soaring musical notes they can produce. Music seemed to be an implied component of the pictures in this context. You could supply your own inner soundtrack. William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops came to my mind. These haunting, melancholic pieces incorporate the degradation of lengths of oxide tape, and thereby of the sound recorded on it. They are the sonic equivalent of Judy’s photographic decay, and would provide a good aural backdrop.

Karen Tarr became fascinated, whilst researching the church, with the story of St Olaf, to whom it is dedicated. His sanctification was a post-mortem bestowal. There would have been little enough to justify it in his life. He was a Viking warrior king who attempted to unite (i.e. conquer) a divided Norway, before dying in battle in 1030. his body soon became the locus of a selection from the standard book of miraculous manifestations. A healing spring bubbled up from beneath the body, lights appeared in the sky, bells rang where no human hand was present to pull the ropes, and the corpse remained fresh and undecomposed (composed?). Indeed, the hair and nails continued to grow for years afterwards, which provided a ready source of relics, and thereby also pilgrims and a steady income for the church.

Karen presented a modern take on this exploitation of credulity, the thirst for the holy and the need for exemplary figures to revere. She set up a merchandise table such as you might find at a rock concert, and sold her own Olaf relics. Woven friendship bands resembled the blond braids of his hair (which mysteriously changed colour at some point during his posthumous sainthood), whilst axe-head badges represented the uneasy attempt to translate a weapon of bloody slaughter into a holy symbol. There were also T-shirts depicting a cloaked and armoured Olaf standing poised for action over the belly-up corpse of a freshly slain dragon. It’s an image which has far more to do with Norse mythology than Christian iconography, but accurately reflects the way in which he was represented in the medieval period. Karen writes that she drew on Marvel Comics and The Game of Thrones for inspiration. But is also very much resembles the kind of picture which might have graced a heavy metal album cover in the 70s and 80s. Printed on a T-shirt (black, of course), it became a piece of imaginary rock merchandise. This pointed to the way in which rock stars and their celebritocratic brethren have become the focus for latterday verneration.

Karen also hung her own panes of stained glass (actually semi-transparent paper in cardboard frames) from the altar screen. They formed a series of suspended rectangles which contrasted with Judy’s crosses and created a sense of balance. Brightly coloured, naively childlike flower petal patterns were boldly outlined over printed monochrome photographs of the church’s interior. The exterior view peered into the mysterious interior, the bright world of vibrant living forms contrasting with a rather cold, stony glimpse of a dimly perceived spirit world – a shadow realm.

Katie Scott Hamilton’s Friday Night Saturday Morning shifted Alan Sillitoe’s weekend ritual (and the film to which his novel gave birth) back a day. It reflected upon the church’s presence over the years, decades and centuries in a quarter of the city with a particular historical character. It’s in the upper part of the West Quarter, always a poor area, and now a nexus of clubs and pubs where binge drinking is the weekend sport. Katie arranged a tumbling cataract of images and objects down the narrow, spiralling stairs which disappear up into the tower. It was a torrent of memory and booze; a vomitous ejecta of historical continuity and momentary, ecstatic self-oblivion. The still, composed faces in faded black and white portrait photos found themselves adjacent to outlined heads whose features were entirely absent. The sacred and profane were placed side by side. Cider bottles rested on hymnals, wine bottles on hassocks, and further stencilled outlines of bottles and glasses were sprayed onto Communion pages and placed on the spread-out field of an altar cloth and the purple river of a priestly stole. Holy texts were rolled up and rammed into bottlenecks, messages to be cast adrift with desperate hope (or alternatively a preparation for Molotov cocktail mayhem). Phrases and buzzwords from the modern lexicon of subtle enticement and direct inducement were stencilled in bold, shouting letters over more torn-out biblical pages: BOGOF, Drink Up, Happy Hour. A picture of a memento mori skull stood out starkly amidst the general jumble, reminding us of the end which we all have in common.

There was a further fall of pages at the back of the church, fluttering in a frozen instant down the length of a column from the top of which a brightly painted angel surveyed the dispersal of words. The white pages fanned out towards the bottom, as if they were a spray of crashing foam at the end of a torrential waterfall, or had just been blown and scattered by a sudden gust of wind. Simple modern phrases offered a reductive headline version of the texts below, diluting the moral and philosophical complexities of religion into bland self-help homilies, egotistic declarations of personal divine love and self-protective accusations thrown at the non-believer. It’s a palimpsest which marks the withering of language and spirit.

Steve Brown set up a couple of prayer boards towards the back of the nave. He was intrigued by the messages pinned to the church boards, and the glimpses of personal crises, loss and longing they afforded. His work was a pop art altarpiece diptych, a collage of photos, record and tape covers, lyrics and associated ephemera, combined with more distressing material reflecting suffering in the present moment. The panels centred around two very different pop stars, who stand here for contrasting and largely opposed views of religion and the nature of belief, as well as the nature and purpose of art. On the left is John Lennon in his post-Beatles Plastic Ono Band phase. An unglamorous, roughly-bearded photographic portrait was pinned up adjacent to printed chords and lyrics and a reproduction of the Ono Band LP. The cover shows John and Yoko reclining together against the trunk of a broad-branched oak tree. It’s a paradisal image of peace and repose which belies the torment and self-excoriation of the record itself – or which is, perhaps, the outcome of its cleansing catharsis. This is the early 70s Lennon of primal screaming and systematic demythologising, of naked revelation and a striving for raw, unornamented honesty. Steve quotes Lennon’s definition of the divine in the song God, taken from the Ono Band record, which best embodies the qualities mentioned above: ‘God is a concept by which we measure our pain’. Lennon becomes an icon of suffering, his own exposure of his scarred and bleeding soul giving soul to others experiencing torments of their own. Steve includes images of self-harm, along with alarming statistics about its rise amongst the young; and also images and statistics from the current conflict in Gaza. These encompass suffering on a very personal, psychological level (an interior suffering) and on a communal scale, the latter the result of intractable political processes with religious beliefs at their core.

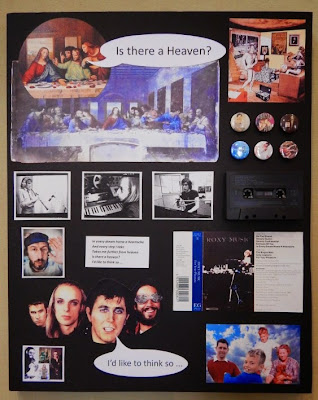

The second panel moves away from the slightly messianic tenor which rock adopted in the wake of the sixties, and returns to pop as an arch construct of colourful surface and bright artifice. Bryan Ferry (and early Roxy Music) was the central icon here. As a self-consciously auto-manufactured pop star, he becomes a natural component of a pop art collage. Steve gave a nod to the visual origins of British pop art by including a photo of Richard Hamilton ( a personal icon?) and a cut-out of his seminal pop collage ‘Just What is it That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?’ Three are parallels with Karen Tarr’s merchandise stall, with a row of pop group badges presenting the rock star as the contemporary object of veneration, with a relentlessly marketed production line of relics and sacred ephemera to supply the demand for signs of devotion. Da Vinci’s Last Supper was co-opted into the collage, placed near the top of the board. One of the disciples leaning over towards Jesus asks ‘is there a heaven?’, the question circled in a comic book speech bubble. The answer comes from Ferry, standing at the head of his own disciples, the Roxy Music band, a knowingly artificial pop star smile fixed on his glam-painted face. ‘I’d like to think so’ he replies non-commitally, in like pop comic speech-bubble fashion. (a Lichtenstein link). The religious representations of Renaissance art are superseded by pop iconography, its divinities, saints and angels by pop demigods. It’s here that people are as likely to look for comfort and answers now, Steve suggests. A Roxy cassette is present as a resonant object. A defunct medium (well, maybe not quite), it becomes a repository of memory, of remembrance of things and people who have passed from the world. Steve adds a touching personal note by attaching a family photo and echoing Ferry’s breezily agnostic response to the question of the afterlife and the persistence of being. Ferry is made to represent a bright pop optimism which deliberately chooses not to delve too deeply into troubling matters, spiritual or worldly. Rather it revels in elaborate artifice and colourful surface appearances. He is set against Lennon’s spiritual disembowelment, his early 70s puritan aesthetic of art as unornamented self-revelation. In some ways, then, Steve is replaying the Reformation; and this pop dialectic demonstrates how much the eternal questions which religion addresses still matter.

Ruth Carpenter placed a series of studies of heads above a pew at the back of the church. Each drawn in a monochrome shade (white on black, yellow, ochre), they took on a spectral aspect, dignified and attentive ghosts returning to a place which was central to their lives. They joined and became a part of the religious iconography which surrounded them, and reminded us that the church is the congregation, the building merely a shell to house it. Name plaques written in different typographies rested on the back of the pew beneath the portraits. They indicated title and position, either in the family or the community: son, esq., parent, daughter, worker. The hierarchies implied by these definitions were fixed, and the regular reserved pew position was a mirror of status in the world beyond. These titles, with no individuating names appended, stand for the anonymity which clouds so many lives throughout history. None were worthy of the memorials which line the walls and floors of the church. Ruth gave them a face in her work, providing an imaginative memorial to the legions of the unknown and forgotten.

Katie Scott Hamilton also presented a series of portraits which reflected upon the generations who have passed through the church. She quoted a comment left in the visitor’s book: ‘thousands pass by without heeding’. The obverse could also be true; thousands pass by without us heeding them. Most people we pass will forever remain anonymous and unknown to us. Katie arranged a large number of mainly standard-sized pages bearing the same outlined head, gazing upwards as if in veneration. A Vesalius anatomical icon, stripped to vein and muscle. The design was identical. We were seeing beneath the skin to the common corporeal basis of humanity. But this commonality was lent great diversity through the use of different media, different materials and different colours and techniques of reproduction. Some were outlined on tracing paper, giving them an evanescent insubstantiality; some were tapestries; some were stitched in bright threads; some were printed, some drawn. One was overlaid on a section of an Ordnance Survey map, roads forming blood vessels, contours giving dimensionality to the hollow head. Another was placed over a reproduction of part of a 17th century map of Exeter, the eternal spirit of the city. They were all the same, and yet displayed an infinite, endless variety.

Ruth Carpenter fixed further pictures onto the stone columns. Her small scale photographs inserted tiny windows into these solid structures, which bore the load of the roof, and made them seem less substantial. In the heart of the church, they looked inwards, but also out onto the world beyond. In the stained glass which she’d carefully framed in her photos, primary reds were prominent. This gave them a bloodshot look, a dully throbbing morning after haze. In one, a white pane was flushed with swirls of red, blood clouding in a glass of vodka slugged back after a punch up. Another incorporated a passing bus, which provided its own blocks of red livery. Ruth also added another photographic work, a Pieta Mary with sorrowfully downcast eyes. Masking streaks of light made it look as if she were submerged beneath crystalline water.

Clare Heaton drew on fairy tales and The Red Shoes in particular for her work, which bore the collective title ‘Our Moral Fabric’. Filmaking partners Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger used the story of the red shoes as a parable for the all-consuming nature of art and the sacrifices which it demands. The presiding spirit here seemed rather to be Angela Carter and her collection The Bloody Chamber, however, the stories in which explored the symbolism embedded within fairy tales and folk legends. Clare created a flat representation of a pinafore dress stitched together from pages of the Bible. Its prim collar was made from semi-circles of cu p-cake cases. This appeared to be some kind of communion dress. It was hung up on the wall adjacent to the font. It was a significant placement, the font having associations with motherhood and the expectations and duties which attached to becoming a woman in the traditional communities for which the church stood as moral arbiter and guardian of social propriety. Beneath the dress was a small row of smashed egg shells stuck to a wooden board. There was evidently some level of symbolism at play here, possible operating on many levels at once. They could represent the emergence of the individual self, the transition from childhood, or the desire to resist the pressures of convention and expectation and not have children. Colourful paper butterflies detached themselves from the black and white surface of the text patterned dress and settled on the wall around it. The idea of flight as a symbol of freedom, and of spiritual lightness, takes us back to Judy Harrington’s decaying bird wings. The butterfly is also a creature symbolising transformation and rebirth. Its emergence from the pupa signals a complete metamorphosis, and trace of the caterpillar it once was wholly eradicated. The butterfly is also associated with the soul and with metempsychotis, the transmigration of the soul beyond the mortal plane after death.