Richard Ayoade’s film The Double draws on a long tradition of stories which confront the protagonist with a shadow self which threatens to usurp, undermine or derail his or her life. These include Edgar Allan Poe’s William Wilson )filmed by Louis Malle in the 1968 Poe anthology film Spirits of the Dead), Hans Christian Andersen’s The Shadow (1847), and the novel which Ayoade freely uses as source material here, Dostoevsky’s The Double. The double in fiction is often a manifestation of a part of the self which has been repressed, or which fills out a lost or undeveloped aspect vital to the integration of the whole person. The splintering apart of warring halves of the persona can also give literal embodiment to a state of state of mental crisis, projecting a conflict raging across the internal landscape onto the external world.

John Clute, in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, draws a fine distinction between the double and the doppelgänger. A double may be unrelated to the protagonist, unattached physically or spiritually, whereas ‘a doppelgänger is always intimately connected to the person in whose footsteps he walks’. It ‘may be a projection of the original person whose likeness it takes or mocks’. Given that Simon James’ double, James Simon, presents him with a mocking version of the outgoing person he cannot be, as well as growing evidence of his own invisibility and status as a non-person; and given the physical link which is revealed between them towards the end of the story, they can perhaps be thought of as subject and doppelganger than as doubles.

The urban world of Ayoade’s film is an indeterminate zone, with no specific geographical or historical locus, or defining characteristics of any sort other than a vague latter half of the twentieth century timeframe derived from the background technology. Its expressionistic set design, cinematography and sound push it beyond the authentic replication of real place or mood and takes us into the territories of psychologically resonant architecture and interiors. The characterless city in which Simon James lives and works is shaded in drab, muted colours, with a tendency towards chiaroscuro shades of grey. There is no enlivening brightness. The daylight is smeared, as if having to penetrate through a grimy glass dome. The interiors have the sickly yellow glow of striplighting, which makes everybody look sallow and jaundiced. The sky is occluded, shuttered off in the windowless labyrinth of the office or swallowed up in the shadowed canyons between the brutally monumental slabs of the housing blocks.

Simon witnesses, with mute horror, a bird being spat out of a duct mouth to land with a wet thud on the upper shelf of an inaccessible, glass-fronted storage cupboard. It has presumably been sucked from the sky by a vent on the roof somewhere far above. There it lies, an eviscerated lump displayed like an anatomical specimen. Simon glimpses it again later in the story, untouched and slowly rotting away, roughly filed in its sealed-off stationery mausoleum. It serves as a stark symbol of the death of the soul in this deadening environment, left to wither and decay in airless confinement rather than soaring in expansive flight.

Office technology is monumental and domineering, photocopying machines great glowing hulks which judder and shake into threatening motion as if powered by small nuclear plants. Individuals are hived off into dim wooden pens like so many productive farm animals, faces wanly illuminated by the dull green radiance of computer screens, the bulky extension of the encased tube at the back adding to the air of suffocating claustrophobia. This is a place in which people are a component of an overarching machinery, subservient to the unquestionable logic of a mechanised system the output of which has become almost irrelevant.

The expressionistic tenor of the film extends to its sound design. The office is filled with subterranean rumblings and the incessant grind and chatter of overcharged and unstable technology makes it sound more like an industrial plant in which heavy machinery rolls and booms through its violent processes. The space between the housing blocks is scoured by a bleak wind, which sounds like it has blown in from some chasmic void. It makes of it a blasted no-man’s land, to be hurried across with as much haste as possible.

Is this the drear, depersonalised world which has shaped our hapless protagonist, or is it an expressionistic projection of his inherent nature, a subjectively distorted perspective. Perhaps a little of both. Simon literally projects a long, angular shadow behind him when he pauses before entering his building one night, sometime after his double has set his life on its downward trajectory. It’s almost too perfect an image, reproducing the impossibly jagged and distorted black and white shadows of the German films of the 20s which established the cinematic language of expressionism. It could have been designed for use on the poster. The subjective , self-conscious nature of this imagery is also made clear when Simon walks down his apartment block corridor with a spring in his step, filled with the sudden and surprising possibility of happiness after his meeting with Hannah. The lights fizzle and flicker above him, bathing him in brief pulses of bright, primary colour.

In such a drearily entropic, drained world, imaginative escape of some sort becomes necessary for survival. Simon zones out to the arpeggiated synth soundtrack of a ridiculous space opera. He drinks in the tough guy heroics, and the simplistic life or death choices which the silver-suited, ray gun wielding lead character makes as a matter of course, always accompanied by some macho epithet. The gulf between the life of a downtrodden nobody (or ‘creepy guy’) and the action hero he dreams of is as painfully gaping as it always is in such wish-fulfilment fantasies. It’s the kind of vapid escapism which, in the end, only serves to make the real world that little bit more unbearable.

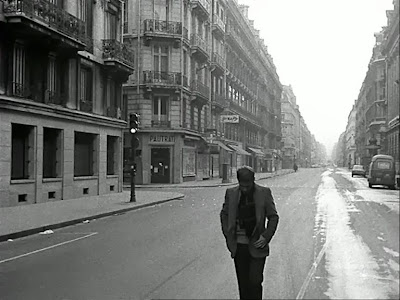

Hannah escapes through art, drawing sketches which she then tears into scraps. She gazes at the fragments which adhere to her fingers as if they were precious mosaic bricks, before brushing them of into the rubbish chute. This furtive practice suggests that art and creativity is seen as a shameful impulse in this world, unproductive, self-indulgent and useless. Simon rakes through the rubbish bins beneath the mouths of the communal chutes and collects these paper fragments, pasting them back together again in a scrapbook he devotes to the reconstructed pictures. It’s a scenario reminiscent of one of the plot strands running through Georges Perec’s absurdist novel Life: A User’s Manual (La Vie Mode d'Emploi in the original French), first published in 1978. A hugely wealthy Englishman named Bartlebooth learns to paint to a high standard and travels the world producing landscapes at various ports. He sends his paintings back to an apartment in Paris where they are cut into challenging jigsaw puzzles by a master craftsman. He then reconstructs them, and when they are finished sends them back to the place where they were created. Here, the watercolours are washed off, leaving a blank, scarred canvas which Bartleby claims as his own. Another Perec link is made through the first of Hannah’s sketches which Simon puts back together. It’s a view of the back of a head, a figure looking at itself in the mirror. The reflection is not of a mirrored face gazing back at itself, however, but a reproduction of the back of the head which we see. This is a conceit which Rene Magritte used in his painting La Reproduction Interdite (Not to be Reproduced). A poster of it is stuck to the wall of the room in which the protagonist of the 1974 film Un Homme Qui Dort (A Man Asleep) lives. It was a film which Georges Perec worked on with director Bernard Queysanne, adapting his own 1967 novel. Like The Double, it is about a young man falling further and further out of sync with the world around him, slipping into a shadowy state in which he becomes like an insubstantial ghost drifting through life. The narrative progression of both films charts a descent into escalating mental disintegration and despair.

Magritte's painting in Un Homme Qui DortAnother very obvious literary influence is Franz Kafka, who might as well share a screenwriting credit as spiritual advisor. The Kafka characteristics are all present: the crushing bureaucracy; the blandly indifferent figures of petty authority who operate according to abstruse yet immutable laws; the concern with the fine detail of hierarchies and of power within relationships, and the unceasing struggle to gain recognition or a degree of self-determination; the absurd dialogue which can turn logic inside out and switch from innocuous pleasantry to undermining attack within the turning of a phrase; and the subjection of a powerless individual to the arbitrary dictates of an incomprehensible system, or merely to the chance operations of the uncaring universe at large. The presence of a little Kafka lookalike (played by Craig Roberts, the lead actor in Ayoade’s first feature, Submarine) is a nod to his pervasive spirit. Ayoade has also talked about the influence of Orson Welles’ Kafka adaptation The Trial (1962) on the mood and look of his film.

Other film references seem to adorn The Double, Ayoade’s cinephiliac side bubbling irrepressibly to the surface. Hannah has a blue glass mobile similar to the one which Juliette Binoche gazes at in Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Three Colours: Blue. It’s a visual echo which draws a comparison between the two women leading lonely lives in their solitary flats. The periodic rumbling in the café, presumably indicative of subway trains passing directly underneath, is reminiscent of the shuddering passage of the heavy trains which sets furniture and glasses rattling in the bar in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (and later accompanies the telekinetic shifting of the glass along the table by the damaged young girl). It’s a film which shares, for the scenes set outside of The Zone, The Double’s oppressively colour-drained palette. Simon’s use of a telescope to spy on the life on display through the windows of the apartments opposite, and at Hannah’s in particular, inevitably recalls Rear Window. But perhaps a more appropriate comparison, given the Eastern Bloc drabness of the housing, would by Kieslowski’s A Short Film About Love.

Terry Gilliam’s Brazil shares similarities in its building of an exaggerated, absurd architecture of bureaucratic oppression. It’s also similar in its depiction of a society in a state of dulled, stupefied inertia, lumbered with antiquated systems and baroque. barely functioning technologies; and in its general air of pervasive grubbiness and corrosion. There is none of the brightly brittle emphasis on the artificial promise of escape through consumerism found in Brazil’s mutated post-war Britain, however. The world of The Double builds more upon an Eastern Bloc variety of austerity. There seems to be a lot of unspoken emptiness and absence, a fearful quietude which has settled over everything. Vast importance is attached to work and position, and the moral backbone which their diligent pursuit provides. But this work has no readily apparent purpose. A militaristic authority figure, the Colonel, is presented as a gleamingly spotless, airbrushed icon, imbued with an almost spiritual power of redemption. To gain his blessing means attaining a higher state. James Fox lends him a suitably aristocratic bearing, vaguely benign but detached and unapproachable.

Such influences are used lightly, however, and with conscious application. They build up layers of resonant association which add further depth to particular scenes. Ultimately, The Double creates its own world, visually self-contained, shot through with bleak absurdist humour (just as Kafka can be) and full of idiosyncratic and finely observed detail. It is, I feel compelled to conclude., a singular achievement.