Saturday, 26 April 2014

Soft Estate at the Spacex Gallery

Artist and academic Edward Chell has gathered together a motley band of explorers for the new Spacex Gallery exhibition Soft Estate. They are all set on venturing into the seemingly blank and barren spaces of urban edgelands and interstitial no-places, intent on unearthing unexpected riches and neglected histories from what at first glance might seem unpromising terrain. By focussing on the wildernesses of the automotive landscape and the monumental ruins of the modernist era, the exhibition positions itself at one end of a continuum which connects it with historical artistic and aesthetic tastes and moods. It’s notable that one of the artists here, Laura Oldfield Ford, also has work in the Tate Britain Ruin Lust show. Her pictures there are ambivalently placed in the Pleasure of Ruins section, near to watercolours of ruined abbeys by JMW Turner and John Sell Cotman, and parallel with John Piper’s large, semi-abstract 1961 painting The Forum. Perhaps significantly, her paintings of battered grey estates and portraits of their inhabitants are placed directly opposite Joseph Gandy’s hovering view of John Soane’s new Bank of England plans depicted, at the request of the architect, as future ruins.

Edward Chell’s own work sprouts up throughout the exhibition, like the hardy weeds and scrubland plants which he celebrates. This is the unglamorous species of vegetation which goes unprized, and is uprooted when it strays into land cultivated by cursing gardeners. But it is resilient and indicative of the profligacy of nature, its stubborn insistence on adapting to and colonising any environment, no matter how inhospitable. Chell’s work is concerned with the artificial landscapes created by man to accommodate the car economy. He is fascinated by the new possibilities this has afforded for nature to flourish in areas hostile to human presence. This principally means motorway verges. The title which he has chosen, Soft Estate, is a term which refers to such spaces. It recognises that they have become distinct habitats fostering a surprising variety of life.

Chell makes ironic play with the proximity of a uniform, mechanised and ruthlessly functional manufactured landscape, seemingly intent on sealing inconvenient nature beneath a hard coating, and the plant species which go wholly unnoticed by those speeding past in their aluminium and moulded plastic pods. Mantel Piece (2013) arranges a varied array of highly polished silencer boxes from the underbellies of cars end up, moulded onto stands. The open ends of connecting pipes give access to the hollow interior like the narrow mouths of flower vases. On the flat sides, silhouettes of tough, straggly plants are etched, giving them a sense of permanence and indestructibility.

This impression is further created in works displayed in the smaller upper gallery. Eclipse (2013) covers the wall with evenly spaced square plaques, which are lacquered to give them a hard reflective shine and make them look like Chinese porcelain. The outlines of plants found on motorway verges are painted onto the surface of the plaque, and the whole looks like a taxonomical collection, pressed into lifeless, memorialised permanence beneath the translucent varnish. Three large drawings on rough-edged paper use dust gathered from motorway verges as the basis for mixing together a new graphic medium. This is used to create more silhouettes of hardy roadside plants. The means of producing the pictures points to the impermanence of the hard manufactured hide layered onto the surface of the world by human agency, which is subject to the same forces of erosion as anything else on the planet. It will, in its turn, break up and be ground down to become part of the topsoil in which vegetable life will establish itself in its own slow time. The glowing granular gold with which these silhouettes are filled suggests an alchemical process, the base material of the motorway transformed into irrepressible, outspreading life. The large scale on which these plants, generally considered unworthy of attention, are rendered gives them a noble, heraldic aspect. Michael Landy has similarly rendered weeds and wasteground plants with a fine art precision. By the very effort expended and attention granted, this lends them a new and magnified importance, directing our attention to the neglected and disdained in the world at large.

Chell’s four large paintings in the main gallery also make a significant link between the medium and the subject matter. These depictions of motorway verges, with flowering banks filling the foreground and most of the frame, are finely detailed in buttery yellow oil paints. These are daubed onto a smoothly reflective surface of shellac, rolled out over the linen field of the canvas below, which provides a dark contrast to these two-tone compositions. This hard shellac surface echoes that of the built-up motorway environment depicted. But the main focus of the pictures, as mentioned, are the verges, which glow with a flowering yellow radiance, a soft surface which belies the brittle, chitinous backdrop upon which it lies. There is no sign of human presence in these pictures. The overexposed, bleached light hints at an intense solar radiation, the burning glare of a post-human future, or one in which humanity has been forced from the surface of the world. The spirit of JG Ballard inhabits these depopulated concrete and tarmac landscapes. Their linear regularity, softened by nature’s incursions, are suggestive of inner topographies in which all inessentials have been pared away. Ballard’s presiding spirit hovers throughout the exhibition, in fact. The clipped psychogeographical musings of Iain Sinclair (particularly in London Orbital) and the wanderings of Robinson in Patrick Keiller’s films are further literary and cinematic satellites orbiting the work here.

Other literary and artistic precedents and pointers are invoked by Chell more directly. William Gilpin, John Ruskin and William Wordsworth are given their own personalised custom car plates. Some kind of progression in the aesthetic view of the ideal landscape is traced in this roll call of worthies, and the manner in which they are presented. Gilpin formulated the notion of the Picturesque in the late 18th century. This moved away from the rigorous formality and order of classical landscapes, which martialled landscape features into carefully controlled patterns. Gilpin’s idea of the aesthetically pleasing landscape incorporated rougher, less linear and symmetrical natural forms (deciduous trees, for example). But it was still controlled and made hospitable to the presence of the human wanderer, if only through the careful framing and placement of the individual elements. Nature was subtly altered and improved upon.

Ruskin played a key role as a critic in the development of Romanticism in the early nineteenth century. This drew upon the Picturesque, but emphasized the more rugged elements. In its valorisation of the sublime, the mountainous, cavernous and chasmic, and the pleasurable terrors they inspired, it also set the individual against their surroundings rather than placing them comfortably within them. The landscape and its attendant weather became something against which to test the heroic soul. Wordsworth stands for the literary side of the movement. He is another bridging figure, developing the Romantic worldview in his poetry from the Picturesque tastes which preceded it. Both movements, and the work which they gave rise to, still exert a powerful influence on the way we think of landscape and nature, and what we find beautiful in them, to this day.

The different styles of lettering on the car plates symbolise changing tastes over time. They also draw parallels between the modern car culture, which has transformed the landscape physically and in the way we see it (generally framed in a windscreen or window), and the 18th and 19th century worlds in which these aesthetic viewpoints arose. Gilpin travelled in horse-drawn coach on his picturesque tours of England, at a pace which made discoveries of special places all the more pleasurable. Wordsworth could write about he coming of the railways and the steam age in his 1833 poem Steamboats, Viaducts and Railways, not without a certain measured optimism, or at least philosophical acceptance. Ruskin wholly rejected industrialisation in his later life, yearning for a return to human craftsmanship rather than machine manufacture. But his promotion and approval of the Gothic revival as the appropriate architectural style for the age certainly had its effect on the look of the world the rapidly spreading railways made. The car plates look forward from this world to one in which pre- and post-war Shell Guides pointed the way to Picturesque and Romantic views, with accompanying illustrations by some of the prominent English landscape artists of the time such as Paul Nash, Eric Ravilious and Graham Sutherland.

Chell further explores this link with more signs on the walls. These can be found in parts of the gallery not generally used for showing art – the inbetween places which the visitor usually walks obliviously through. Chell thus reflects the theme of the exhibition in the very manner of its display. His signs are even put up on the outside walls of the Spacex, originally competing with brightly coloured bill posters declaring Luke Haines Is Coming (he isn’t any more, alas). The aluminium plates use the blue background with white borders and the lettering which are the uniform graphic style of motorway signs. They employ the same reflective materials which make the message stand out with optimum visibility at a distance. Rather than distances or directions, however, these signs offer outlines of flowering verge plants (hemlock, ragwort and lady’s bedstraw), making roadside icons of them. These bring to mind the sign which Patrick Keiller keeps returning to in his film Robinson in Ruins, zooming in to pick out the detail of lichen which adds its own congruent element to the overall pattern. Another sign frames lines taken from a recent variant on Romantic nature poetry by Andrew Taylor, which is subjected to a modernist fragmentation of the regular metre. The instantly recognisable blue of the signs contrasts well with the red brick in which they are set. It was a good idea to have the exhibition spreading out to the exterior of the gallery like this. Unfortunately, it does have its hazards, and Songbird, the sign with the poem, appears to have been nicked.

Other artists respond to the idea of urban edgelands and automotive landscapes in varying ways, which contrast with each other in a stimulating and thought-provoking manner. In the lobby, several of Simon Woolham’s drawings and lithographs are hung, their white surfaces illuminated by the sun which pours through the windows in the mid-morning and early afternoon. These are like obsessive and very precisely scribbled doodles, tightly compacted and clearly delineated around the edges. They seem to depict mazes, pens and tunnels, confining structures and boundaries. To various degrees, these structures have begun to unravel in certain parts, as if worn by age, or pulled apart and kicked in. A ‘pop up’ book contains more of these expressive no-places, although the pop-ups and cut-outs seem to offer no ingenious structural delights or surprises rising from the page at you. They don’t pop up at all. The accompanying text evokes the world of enervated teenagers, boredom alleviated by sullen vandalism and ‘shagging’. The language and behaviour is vicious, wild and nihilistic. These are deserted borderlands which have been turned into occupied territories, in between spaces for in between ages. They are half reconstructed (with the cuts of superimposition still evident) through imagination and memory (which always leaves ragged, unfinished edges). There is presumably some irony intended in the requirement to don white gloves to turn the pages of Woolham’s book – another example of fine art techniques and associations lending nobility to the legions of the disdained and overlooked.

George Shaw also depicts the worlds of childhood estates where he grew up in his paintings, drawings and lithographs of the estates in the Coventry suburbs where he grew up. It’s the lithographs which are on display here. I first saw a number of them in an exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge alongside the Michael Landy ‘weed’ prints mentioned earlier. They show the borderlands where the built environment abuts areas of scrubby nature. It’s a messy, ill-defined boundary zone, with rectilinear and organic shapes and forms thrown into unplanned proximity, sometimes harmoniously, sometimes not. This could be seen as the incursion of a now shabby Picturesque into human territory, or as the pushing back of the Picturesque by the expansion of dense human habitation. In The Birthday (2012), a stand of trees gathers in the shade at the edge of a block of sunlit white buildings. I seems as if they are looking on, poised to shuffle a bit further inwards during the night, when nobody is watching.

Either way, incursion or pushing back, these are uneasy spaces. The Picturesque is no longer a comfortable, pleasurable place to inhabit or look upon. The absence of human presence becomes inherently threatening. A path curves like a stream towards the black cave mouth of an underpass. The title of the picture, The Gamble (2012) makes explicit the danger which might loiter within. In Playtime (2012), the rope raggedly dangling from an outstretched gibbet arm of a branch looks as if it might be the remains of a noose from which a pendant body has been cut.

Laura Oldfield Ford’s 2011 Walsall Drift series also depicts housing estates, high-rise blocks and their borderlands – canals overshadowed and superceded by flyovers, gaps of horse-gnawed scrubland, motorway footbridges and derelict breweries. Her pictures are, like those of Shaw, filled with inherent violence and despair, voiced in the writing which is scrawled and incised across them. This is a graffiti which is part observation and pyschogeographer’s field notes, part projection of inner states. The words are obscured by smeared washes of pink, the messy traces left by attempts to scrub out graffiti. A similar attempt at erasure surrounds the head of one of the rare human figures found in the exhibition with a bubblegum cloud. He is a man standing with his bicycle beside the motorway footbridge. The disparity between the two modes of transport, and the evident fact that he will have to (or has had to) heave his bike over the bridge, suggests that he is almost as out of joint with his age as Gilpin might be if he slipped through time and found himself riding through the modern Walsall landscape.

In Walsall Drift 4 (Tower Blocks), the graffiti is more profuse. Its surrounding pink miasma fails to occlude the urgency of the story it tells of a woman living in one of the flats, the ‘mother of a bright ten year old’. The reductive delineation of her room’s contents gives a sense of confinement, of having gazed at these furnishings too long and too often. It’s like a modern variant of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s classic story of domestic mental disintegration, The Yellow Wallpaper. The feeling here are so intense that they leak out like curling smoke, filling the air with half-heard murmurations. There is a fiercely moral aspect to Ford’s pictures. Ruskin, with his insistence upon the necessity for art to have a moral dimension, would have approved of the sentiment, if not necessarily the mode and tenor of its expression. Laura Oldfield Ford’s work is gaining a great deal of recognition this year. She was included in the Ruin Lust show at Tate Britain, and will soon be a part of the British Library’s exhibition Comics Unmasked: Art and Anarchy in the UK.

As previously mentioned, there is a good deal of potential overlap between Soft Estate and the Ruin Lust, the Tate Britain exhibition. Day Bowman and Robert Soden could certainly have been included in the latter. Bowman’s Gasometer 4 (2011) is a large, semi-abstract painting in greys and whites, the barrel shaped form of the subject filling the foreground, as if viewed in looming close-up. The spattered ‘spillage’ of paint is akin to industrial spoil. Two smaller pictures from the 2012 Weymouth/Portland series combine painting and collage, and studiously avoid the attractions of the picturesque offered by the Dorset coastal locales. The Weymouth here is more like the secret militarised landscape portrayed by Joseph Losey in his 1963 Hammer film The Damned. The razor wire topping a security fence is outlined against a fierce orange sky, with explosions of cut-out purple flowers overlaid. Another gasometer is situated in a barren space bordered by chain fence links and blearily burnished by the unsparing sodium glare of night streetlighting. The picture is divided foursquare into discrete sections, which both complement and contrast with each other. Pink campion flowers offer the same defiant intrusion of life into the wasteland as can be found in Edward Chell’s work. A painted border at the bottom resembles a fragment of one of Monet’s water-lily canvases. Both paintings have more paint splatter spoil, and the latter has oily black mug-base rings. These look like they might have been made by barrels leaching some chemical effluent.

Robert Soden paints John Piperesque ruins, the rubble of ‘redevelopment’ sites, often in his native Sunderland. The shattered skeletons of buildings rent by wrecking vehicles and the tangled thickets of their wire and twisted iron frameworks hark back to the Turneresque romance of ruins. For a brief period, the urban space is opened up and the sky revealed, the city afforded a more expansive prospect. The Caretaker’s Hut (1985) is set against a complex foreground of tangled weeds and yellow flowers. The hut itself is painted a dark green, suggesting an affinity with this semi-wild environment, to which its incumbent evidently takes a relaxed attitude as far as trimming and taming is concerned. It bears the hallmarks of a hermit’s hut, a feature of many a Romantic landscape.

The same could be said of Guyhurn Layby Sit In Transport Café (2010), one of the photographs produced by the Caravan Gallery, Jan Williams’ and Chris Teasdale’s gallery housed in, you guessed it, a caravan. A converted blue shipping container is lodged in a bower of bright thistle heads and abundant weeds. A short bridge of steps leads to the entrance. It’s like a monkish cell, an enclosed retreat in the semi-wild borderlands. In No Way Out, Thurrock (2011), a roundabout road sign beneath a concrete overpass shows a broken circle ,with stubby radial arms sticking out at irregular intervals. It looks like a broken wheel, a symbol of stasis and inertia. All directions point to the sprawl of the Lakeside shopping centre. There is no way out, no escape, no possibility of pulling free from its massive gravitational attraction. It’s a picture which brings to mind J.G.Ballard’s 1974 novel Concrete Island, a latter day Robinson Crusoe tale about a man marooned on a small patch of land between stretches of the Westway heading out of London.

Another traffic island can be found in the Caravan Gallery’s photograph The Island of Sheppey (2009). This one is a little less busy. It’s partly a visual pun, but also plays with the ideas of the picturesque and the sublime. A small platform edged with curved curb takes the form of the stereotypical paradise island. Instead of a gently inclined, off-centre palm tree, however, it has a battered and extremely grubby bollard. The island also seems to have drifted into a layby, butting up against the shore of a roadside verge. It serves no apparently useful function. In the background below the Thames estuary spreads out in all its muddily expansive glory. The play on perspective suggested by the title (the traffic island as Sheppey) enlarges the estuary channel to an awe-inspiring scale, elevating it the status of the sublime landscape.

Tesco Superstore, Nottingham or Wherever (2006) offers an alternative view of roadside verges to Edward Chell’s nature reserves. The verge here is the hidden reverse of the automotive consumer society. The picture is taken from a perspective beneath the slope leading down from the sliproad curving into the superstore car park. The grassy incline is covered with a drift of detritus, packaging litter from the instantly consumed food tossed out of car windows. It’s an invisible no-space, out of sight and therefore beyond care or concern. There’s clearly a symbolic dimension to the picture. Behind the wry humour, there’s a moral dimension of which Ruskin would have approved.

John Darwell’s photos from the An Allotted Space series (2013) frame details of allotments in a spare, austere light. The Picturesque or conventionally pleasing is studiously avoided. There are no brightly red tomatoes or impressively bulging marrows here. The only real sign of colour and productive growth we are granted is a small string of red chillies, and they have been discarded on top of a compost heap, as if deemed to exotic for such surroundings. Instead, the emphasis is on the provisional nature of the cultivation of these edgeland spaces. This is like land coaxed into life by pioneers in a new world, or survivors in a harsh post-apocalyptic environment. Conical stacks of dead stalks look like miniature hayricks, bathetically echoing a favourite subject of painters of the idealised pastoral. Darwell seems most interested in the use of the recycled detritus of society in the allotment plots (descendants of the medieval peasant’s strips of land). The plastic bottles, mulching bin bags, buckets, chicken wire, corrugated iron and yoghurt pots which are adapted for a variety of purposes. They take their part in a cautiously optimistic new perspective on the Picturesque; one in which nature and consumerism strike a balance within the bounds of a test environment.

A key component of the Soft Estate exhibition is the sound which pervades all corners of the gallery. The poem outside (whilst it was there) sets a scene in which ‘the air cools (and) distantly I hear the hum of motorway’. This anticipates what we hear inside. Tracking down the source, we have to kneel down on the floor of the small gallery to look at a film on the pocket screen of an iphone. The image is reduced to a distant prospect, and it is the sound which disseminates across space. The rush of wind down the motorway corridor blends with the slipstream woosh of speeding cars. In one of two films, both shot from flowering verges, the cellophane flapping loose from a roadside memorial provides a secondary screen, a plastic veil through which to view the rapidly passing world. Human and vegetable time is contrasted, and we are reminded that Death dwells in Arcadia, too.

An alternate soundtrack can be heard by donning the headphones piled atop the tomblike black plastic block of the TV which is the visual focus of Hind Land (2013), a video and sound installation by Tim Bowditch and Nick Rochowski with Matthew de Kersaint Giraudeau. The picture on the screen is a static shot of a concrete bunker, which seems to be contained within this monumental mass. A triangular opening between adjoining spaces lends this subterranean interior a ritualistic aspect – a darkly sacred catacomb. The sounds which fill your head once put the headphones on (which also serve to block out the motorway hum) are suggestive of noisome, chaotic and heavily mechanised activity going on just beyond the stillness of the coolly and symmetrically framed picture. Electronic sputterings, ratcheting clatter and general grinding and shrieking conjure up vast machineries. A sound reminiscent of a heavy stone being cumbersomely dragged across a paved surface creates a gothic ambience. We can assume there may be braziers burning in this adjacent space. Blending in with the sounds of strange industry are traces of human voices. But they are transformed, made strange, metallic and distorted – part of the machinery.

These alternate soundtracks denote the divergent tendencies apparent in the show, the varying positions the artists taken on the spectrum between the sinister and the sublime. The diverse nature and outlook of the work, along with its shared focus, make this a fascinating, stimulating and highly enjoyable exhibition.

Labels:

Edward Chell,

George Shaw,

Laura Oldfield Ford,

Spacex Gallery

Thursday, 17 April 2014

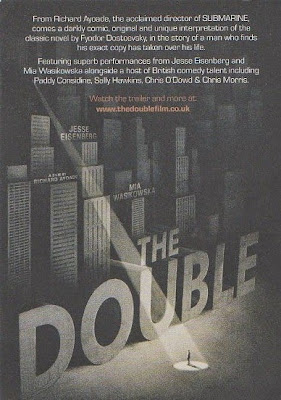

The World of The Double

Richard Ayoade’s film The Double draws on a long tradition of stories which confront the protagonist with a shadow self which threatens to usurp, undermine or derail his or her life. These include Edgar Allan Poe’s William Wilson )filmed by Louis Malle in the 1968 Poe anthology film Spirits of the Dead), Hans Christian Andersen’s The Shadow (1847), and the novel which Ayoade freely uses as source material here, Dostoevsky’s The Double. The double in fiction is often a manifestation of a part of the self which has been repressed, or which fills out a lost or undeveloped aspect vital to the integration of the whole person. The splintering apart of warring halves of the persona can also give literal embodiment to a state of state of mental crisis, projecting a conflict raging across the internal landscape onto the external world.

John Clute, in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, draws a fine distinction between the double and the doppelgänger. A double may be unrelated to the protagonist, unattached physically or spiritually, whereas ‘a doppelgänger is always intimately connected to the person in whose footsteps he walks’. It ‘may be a projection of the original person whose likeness it takes or mocks’. Given that Simon James’ double, James Simon, presents him with a mocking version of the outgoing person he cannot be, as well as growing evidence of his own invisibility and status as a non-person; and given the physical link which is revealed between them towards the end of the story, they can perhaps be thought of as subject and doppelganger than as doubles.

The urban world of Ayoade’s film is an indeterminate zone, with no specific geographical or historical locus, or defining characteristics of any sort other than a vague latter half of the twentieth century timeframe derived from the background technology. Its expressionistic set design, cinematography and sound push it beyond the authentic replication of real place or mood and takes us into the territories of psychologically resonant architecture and interiors. The characterless city in which Simon James lives and works is shaded in drab, muted colours, with a tendency towards chiaroscuro shades of grey. There is no enlivening brightness. The daylight is smeared, as if having to penetrate through a grimy glass dome. The interiors have the sickly yellow glow of striplighting, which makes everybody look sallow and jaundiced. The sky is occluded, shuttered off in the windowless labyrinth of the office or swallowed up in the shadowed canyons between the brutally monumental slabs of the housing blocks.

Simon witnesses, with mute horror, a bird being spat out of a duct mouth to land with a wet thud on the upper shelf of an inaccessible, glass-fronted storage cupboard. It has presumably been sucked from the sky by a vent on the roof somewhere far above. There it lies, an eviscerated lump displayed like an anatomical specimen. Simon glimpses it again later in the story, untouched and slowly rotting away, roughly filed in its sealed-off stationery mausoleum. It serves as a stark symbol of the death of the soul in this deadening environment, left to wither and decay in airless confinement rather than soaring in expansive flight.

Office technology is monumental and domineering, photocopying machines great glowing hulks which judder and shake into threatening motion as if powered by small nuclear plants. Individuals are hived off into dim wooden pens like so many productive farm animals, faces wanly illuminated by the dull green radiance of computer screens, the bulky extension of the encased tube at the back adding to the air of suffocating claustrophobia. This is a place in which people are a component of an overarching machinery, subservient to the unquestionable logic of a mechanised system the output of which has become almost irrelevant.

The expressionistic tenor of the film extends to its sound design. The office is filled with subterranean rumblings and the incessant grind and chatter of overcharged and unstable technology makes it sound more like an industrial plant in which heavy machinery rolls and booms through its violent processes. The space between the housing blocks is scoured by a bleak wind, which sounds like it has blown in from some chasmic void. It makes of it a blasted no-man’s land, to be hurried across with as much haste as possible.

Is this the drear, depersonalised world which has shaped our hapless protagonist, or is it an expressionistic projection of his inherent nature, a subjectively distorted perspective. Perhaps a little of both. Simon literally projects a long, angular shadow behind him when he pauses before entering his building one night, sometime after his double has set his life on its downward trajectory. It’s almost too perfect an image, reproducing the impossibly jagged and distorted black and white shadows of the German films of the 20s which established the cinematic language of expressionism. It could have been designed for use on the poster. The subjective , self-conscious nature of this imagery is also made clear when Simon walks down his apartment block corridor with a spring in his step, filled with the sudden and surprising possibility of happiness after his meeting with Hannah. The lights fizzle and flicker above him, bathing him in brief pulses of bright, primary colour.

In such a drearily entropic, drained world, imaginative escape of some sort becomes necessary for survival. Simon zones out to the arpeggiated synth soundtrack of a ridiculous space opera. He drinks in the tough guy heroics, and the simplistic life or death choices which the silver-suited, ray gun wielding lead character makes as a matter of course, always accompanied by some macho epithet. The gulf between the life of a downtrodden nobody (or ‘creepy guy’) and the action hero he dreams of is as painfully gaping as it always is in such wish-fulfilment fantasies. It’s the kind of vapid escapism which, in the end, only serves to make the real world that little bit more unbearable.

Hannah escapes through art, drawing sketches which she then tears into scraps. She gazes at the fragments which adhere to her fingers as if they were precious mosaic bricks, before brushing them of into the rubbish chute. This furtive practice suggests that art and creativity is seen as a shameful impulse in this world, unproductive, self-indulgent and useless. Simon rakes through the rubbish bins beneath the mouths of the communal chutes and collects these paper fragments, pasting them back together again in a scrapbook he devotes to the reconstructed pictures. It’s a scenario reminiscent of one of the plot strands running through Georges Perec’s absurdist novel Life: A User’s Manual (La Vie Mode d'Emploi in the original French), first published in 1978. A hugely wealthy Englishman named Bartlebooth learns to paint to a high standard and travels the world producing landscapes at various ports. He sends his paintings back to an apartment in Paris where they are cut into challenging jigsaw puzzles by a master craftsman. He then reconstructs them, and when they are finished sends them back to the place where they were created. Here, the watercolours are washed off, leaving a blank, scarred canvas which Bartleby claims as his own. Another Perec link is made through the first of Hannah’s sketches which Simon puts back together. It’s a view of the back of a head, a figure looking at itself in the mirror. The reflection is not of a mirrored face gazing back at itself, however, but a reproduction of the back of the head which we see. This is a conceit which Rene Magritte used in his painting La Reproduction Interdite (Not to be Reproduced). A poster of it is stuck to the wall of the room in which the protagonist of the 1974 film Un Homme Qui Dort (A Man Asleep) lives. It was a film which Georges Perec worked on with director Bernard Queysanne, adapting his own 1967 novel. Like The Double, it is about a young man falling further and further out of sync with the world around him, slipping into a shadowy state in which he becomes like an insubstantial ghost drifting through life. The narrative progression of both films charts a descent into escalating mental disintegration and despair.

Magritte's painting in Un Homme Qui DortAnother very obvious literary influence is Franz Kafka, who might as well share a screenwriting credit as spiritual advisor. The Kafka characteristics are all present: the crushing bureaucracy; the blandly indifferent figures of petty authority who operate according to abstruse yet immutable laws; the concern with the fine detail of hierarchies and of power within relationships, and the unceasing struggle to gain recognition or a degree of self-determination; the absurd dialogue which can turn logic inside out and switch from innocuous pleasantry to undermining attack within the turning of a phrase; and the subjection of a powerless individual to the arbitrary dictates of an incomprehensible system, or merely to the chance operations of the uncaring universe at large. The presence of a little Kafka lookalike (played by Craig Roberts, the lead actor in Ayoade’s first feature, Submarine) is a nod to his pervasive spirit. Ayoade has also talked about the influence of Orson Welles’ Kafka adaptation The Trial (1962) on the mood and look of his film.

Other film references seem to adorn The Double, Ayoade’s cinephiliac side bubbling irrepressibly to the surface. Hannah has a blue glass mobile similar to the one which Juliette Binoche gazes at in Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Three Colours: Blue. It’s a visual echo which draws a comparison between the two women leading lonely lives in their solitary flats. The periodic rumbling in the café, presumably indicative of subway trains passing directly underneath, is reminiscent of the shuddering passage of the heavy trains which sets furniture and glasses rattling in the bar in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (and later accompanies the telekinetic shifting of the glass along the table by the damaged young girl). It’s a film which shares, for the scenes set outside of The Zone, The Double’s oppressively colour-drained palette. Simon’s use of a telescope to spy on the life on display through the windows of the apartments opposite, and at Hannah’s in particular, inevitably recalls Rear Window. But perhaps a more appropriate comparison, given the Eastern Bloc drabness of the housing, would by Kieslowski’s A Short Film About Love.

Terry Gilliam’s Brazil shares similarities in its building of an exaggerated, absurd architecture of bureaucratic oppression. It’s also similar in its depiction of a society in a state of dulled, stupefied inertia, lumbered with antiquated systems and baroque. barely functioning technologies; and in its general air of pervasive grubbiness and corrosion. There is none of the brightly brittle emphasis on the artificial promise of escape through consumerism found in Brazil’s mutated post-war Britain, however. The world of The Double builds more upon an Eastern Bloc variety of austerity. There seems to be a lot of unspoken emptiness and absence, a fearful quietude which has settled over everything. Vast importance is attached to work and position, and the moral backbone which their diligent pursuit provides. But this work has no readily apparent purpose. A militaristic authority figure, the Colonel, is presented as a gleamingly spotless, airbrushed icon, imbued with an almost spiritual power of redemption. To gain his blessing means attaining a higher state. James Fox lends him a suitably aristocratic bearing, vaguely benign but detached and unapproachable.

Such influences are used lightly, however, and with conscious application. They build up layers of resonant association which add further depth to particular scenes. Ultimately, The Double creates its own world, visually self-contained, shot through with bleak absurdist humour (just as Kafka can be) and full of idiosyncratic and finely observed detail. It is, I feel compelled to conclude., a singular achievement.

Labels:

Georges Perec,

Kafka,

Richard Ayoade,

The Double

Wednesday, 9 April 2014

Under the Skin

WARNING: Plot Details Revealed

Under the Skin, directed by Jonathan Glazer, is a film which seems almost deliberately designed to divide audiences. This is due partly to its cool, clinical cruelty, and partly to its semi-formless narrative structure. It proceeds with a meandering drift, and even the most dramatic moments are flattened by the camera’s classically uninvolved eye, holding back and watching from the middle distance. The drift of events and encounters occasionally dissipates, the nebulous focus realigning itself and fixing into moments of complete abstraction. The film opens with just such a moment, a striking formal sequence in which the basic visual and linguistic elements of the human perspective coalesce from fragmented circles of light and the rote repetition of phonetics. These are the elements of cinema, of course – light and language, the script learned and reproduced by the actor, possibly adopting a new accent or intonation. The words we half-hear are divorced from any real meaning and reduced to mere sound, language made strange. The eye which stares out at us lets us know that we will be watching what follows from a radically altered viewpoint. The camera’s eye will represent this new vision. It will be part story, part cinematic experiment, for which we will be the subjects.

We are given no explicit cues as to the central premise of the story at the outset, no prefatory written explanation or scene-setting approach of a spaceship. If some of the lights which dazzle us are indeed a craft of some kind, then it is as abstracted as the spaceship in which Kris approaches Solaris in Tarkovsky’s film. Burning arcs of light, blurred with speed, which might have marked the meteor trail of a capsule plunging through the Earth’s atmosphere, are brought into focus and revealed as the swerving passage of a motorcycle along winding nightroads. We are plunged into a world whose nature we are expected to work out for ourselves. We gather that an alien in female form, played by Scarlett Johansson, is trawling the streets of Glasgow in a white van, picking up human meat in a disturbingly literal sense. She is assisted by brutal, swiftly mobile motorcycling enforcer, a more murderously violent incarnation of Death’s outriders in Jean Cocteau’s Orphée.

The dizzying, disorienting sensation caused by the distanced alien viewpoint is perfectly accompanied and amplified by Mica Levi’s score. Levi, the woman behind the hyperkinetically inventive art-pop of Micachu and the Shapes, produced an atmospheric soundtrack for a sonic journey guiding people around the bewildering spaces of the Barbican in London in 2011. This electronic piece transformed the concrete surroundings into a natural paradise of tropical birdsong and running water. The headphone cocooned wanderer experienced a disconnection from their normal experience of this familiar environment similar to the effect created by the film’s deliberate remove. Although in this case, the electronic sounds provided more of a warm, ambient breeze, wafting between the concrete masses and reviving the utopian spirit of late modernist post-war architecture. Levi’s music for Under the Skin is more in line with pre- and post-war modernist tendencies in classical music. Its skittering, scrabbling, stridulently chittering strings (evoking the anthill or insect swarm) are overlaid with the odd, sensually upgliding glissando line – a disconcerting combination. The style is reminiscent of Gyorgy Ligeti, Giacinto Scelsi or parts of George Crumb’s Black Angels quartet (extracts of which were used in The Exorcist). There are also little burbles and squawks of electronic sound, which suggests a coldly calculating machine-like intelligence at work. Modernist composers’ determination to completely dismantle the structure of late romantic music and reconfigure the separate elements into new patterns and forms led to pieces which sounded strange and alien compared with the familiar worlds of well-tempered melody and harmonic development. This strangeness has made them ideal for accompanying the discovery of the new worlds of SF or for expressing the destabilising, disruptive forces of horror. Ligeti, Penderecki and Bartok have all duly been brought into service, and many soundtrack composers have drawn on their soundworlds. The third movement of Bartok’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta has proved a particularly rich template, and has been directly used in The Shining and the Doctor Who story The Web of Fear. Levi’s score takes its place within this tradition, and does so to great effect.

There is also a disconcerting disjuncture between visual style and formal register throughout the film; abrupt fissures open up between scenes of distanced but largely realistic observations of ordinary life and an ascetic surrealism which leads us into edgeless no-places where boundaries and surfaces are indeterminate and fluid. ‘I’m dreaming’, one character whispers to himself as he walks into such a space, and the alien replies, with soft assurance, ‘yes, you are’. These are voids in which all the cinematic appurtenances of set dressing and digital backdrops, the illusory reproduction of authentic worlds or the creation of new ones shaped from the imagination, are erased. When the men whom Scarlett Johansson’s nameless alien draws into these no-places are gradually submerged beneath the translucent, oily-black surface which she walks over, it’s as if they are sinking into the screen itself, passing out of our vision. The realistic scenes also have a strangeness which derives from their very authenticity. Many of the encounters weren’t staged, but surreptitiously filmed. This extends the cinematic experiment beyond the audience to those on the screen (and those who were filmed but refused consent to appear in the film, or ended up on the cutting room floor). Would it have been better to have a non-star in the lead role? Perhaps, but it would have lessened this extra dimension of cinematic self-referentiality. Because, in a film about the protective and deceptive nature of surface appearances, it’s quite apparent that none of these randomly selected passers-by recognises Scarlett Johansson, the Hollywood movie star, in this relatively de-glamourised guise.

These surreally empty scenes occasionally cross the boundary into hard-edged abstraction, any trace of human presence, recognisable landscape or interior expunged. A linear lava flow of roiling red matter channelled towards a letterbox aperture hints at the conveyor belt transportation of processed human meat (all of which reminds of the alien ‘harvesting’ machines in Nigel Kneale’s 1979 Quatermass conclusion). But this is the most abstracted of gore scenes, presenting us with a rectilinear line of colour rather than a river of blood or steaming heap of guts. The slot towards which it is conveyed expands as we watch until we are confronted with a black screen banded by a single straight line of burning red. Held for a number of seconds, it’s a cinematic abstract expressionism, with a similar refusal of direct representation. It’s one way in which the film attempts to get under the skin, to pass beyond external appearances and search for some numinous quality beyond, some essential human essence – the soul, perhaps.

There are several scenes in which we are faced with a black screen, or one which bleaches out into a searing whiteness. Scarlett Johansson’s blank face becomes blurred in fog, its features reduced to the barest outlines before disappearing altogether. Similarly, we first see her properly within a screen of boundless white light, which threatens to grow brighter and sear away all contrast between her form and the background. As she drives through the night streets of Glasgow, her vigilant, expressionless face morphs with a visual collage of the people she is watching through her windscreen, until she seems to be composed of a billowing mist, suffused with an orange, sodium-lit luminescence. She’s illuminated by a similar light later on, when her body is burnished by the radiance of an old bar heater, making her look like a gilded statue.

This abstraction, the distortion or transformation of the human form into new and strange configurations, its absorption into its surroundings or its total erasure, is a part of the cold emotional tenor of the film. This is another aspect which makes it hugely divisive. It what makes the film have the feel of a psychological experiment at times, like the Voight-Kampff empathy tests in Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, and in Blade Runner. It’s as if we were being presented with a series of self-contained scenes of suffering and cruelty and asked ‘how does this make you feel?’ A baby crying in the teeth of the wind, abandoned and helpless on a heavily, roughly pebbled shore as the tempestuous tide relentlessly draws nearer. And this? A deformed, lonely man offered a hint of companionship and affection which we know will be the prelude to his unpleasant death. Now answer the questions on this form which will precisely map your emotional reaction.

The alien perspective is a SF device which, when brought to bear on the ingrained rituals and routines of modern, everyday life and the assumptions which accompany it, makes the familiar seem strange and less solid. That’s certainly the case here when the Scarlett Johansson alien drives or walks around Glasgow, watching a swarm of Celtic fans, mingling with shoppers in a crowded mall, or tracking late night revellers or isolated individuals striding briskly through the street. We share her viewpoint, the van’s screen becoming a secondary cinema screen for significant periods of time.

The alien can also be taken as a metaphor for the outsider, the nonconformist or the feared and despised ‘other’ in general. This aspect becomes increasingly prominent in the latter part of the film, as the alien leaves the hunting ground of Glasgow, with their ‘safe’ houses, abandons the mobile shelter of the van, and sheds the first superficial layer of skin, the fake-fur coat she has donned at the beginning of the story. The SF alien, with all its manifold potential for metaphor and allegory, is largely employed in this context to lend the central character a blank, affectless view of the world, and a fixity of purpose devoid of any empathy or emotional attachment which is akin to a schizophrenic or psychopathic state of mental disorder. Remove the fantastic elements, and this could be a film about a young woman with profound mental health problems.

In this respect, it shares certain parallels with a previous British film with the same title. Carine Adler’s 1987 film Under the Skin starred Samantha Morton as a young woman traumatised by the death of her mother. She suffers a breakdown and embarks on a self-negating trail or casual, emotionless sexual encounters in an attempt to numb her pain. In the current Under the Skin, sex becomes something which cracks the alien apart, in the end stripping off her protective skin in a literalised metaphor. It is seen as a destructive, violating force, a forceful infection of the human into the body beneath the carefully constructed outer carapace.

The removal of emotional affect, combined with the implicit mission to ‘harvest’ human meat (something made a great deal more explicit in Michel Faber’s source novel), bring an almost unbearable cruelty to some scenes. The wailing baby on the beach and the encounter with the unfortunate man whose head is misshapen by a genetic disorder are calculated to cause discomfort and distress, and are deeply upsetting. They work by creating a sense of empathy and pity in the audience which is not remotely reflected in the responses of the aliens, although their human appearance still leads us to expect it. These two are reductive embodiments of the female and male attributes projected as desirable traits in a heavily mediated world of surface appearances and relentless competition: the seductive, sexy woman who can get anything she wants through the unfurling of her charms, and the brutishly strong action man, capable of ruthlessly battering down any obstruction which blocks the path to his goal. Everything beyond these shallow surface identifiers is unknowable to us. These characteristics represent the skin to which the title refers, easily copied and cultivated from the flood of signs assailing the everyday world, presenting us with the idealised forms of perfection and conformity over and over again. In Scarlett Johansson’s case, the skin is represented by the fake fur coat she buys, and the make-up she puts on to create a mask of artificial sensuality. The man’s skin is his armorial biker’s leathers, which accentuate his broad shoulders and puffed out chest and give him an air of permanently poised aggression. You get the sense that there may be no human flesh, real or facsimile, beneath this stiff hide.

The encounter with the deformed man is the central point of the film, fulcrum on which it turns, beginning its descent into disintegration, its departure from the city into the hinterlands. He hides his swollen face beneath the hood of his coat (his own protective hide) and goes out at night to do his shopping. The Johansson alien (and the lack of a name makes it difficult to refer to her as anything else) asks him about his girlfriends, or whether he has any friends at all. This opens up such an unbearable well of loneliness that it appears to affect even her alien consciousness. Perhaps it taps into some universal knowledge of isolation and alienation common to all intelligent, self-aware life – a condition of being which ignites a spark of commonality which can span even the vast gulf which we’ve witnessed dividing these species. She is infected with a viral microbe of pity and compassion which begins to spread. From hereon in, we observe her steady disintegration. This is in part marked by her loss of language, her retreat into dumb incommunicativeness. She becomes increasingly isolated, drifting uncomprehendingly towards the condition of the man whom she took pity on and allowed to live. She becomes self-reflective in an attempt to understand this newly emergent self, becoming mesmerised by her face and body as seen in mirrors, as if she had been unaware of them before.

To go further inward, to get under the new skin of which she is becoming conscious, she heads out into the Scottish wilds. These provide psychological landscapes which are perfectly congruent with her inner states. The loss of language, the erosion of the ability to communicate, is a symptom of overwhelming feelings of bewilderment, loneliness, fear and loss – feelings which are part of the infecting virus of humanity. There is an element of deliberation here, too. The first layer of skin, the fur coat, is shed and the protective womb of the van abandoned. In this formally rigorous film, the hinterlands beyond the city are the location for a progressive disintegration which reverses the initial integration and efficient fulfilment of duty which comprised the first half. The enveloping Scotch mists, ruined castles through which biting winds gust and empty, silent pine forests in which the slightest snapping of a twig ricochets like the crack of a gunshot are the perfect symbolic backdrops to express a state of alienation and psychological breakdown.

The film’s take on gender begins to change at this point, too. In the first half, the Johansson alien is a female inversion of the horror or serial killer archetype, a coldly manipulative, predatory stalker – a white van woman. But as her psyche fragments and she drifts from her purposeful pursuit, spiralling further inward (and outward), she becomes vulnerable and open to exploitation and abuse. This is very uncomfortable to watch. The base behaviour of the men she encounters, all of whom, with greater or lesser degrees of directness and brutality, are intent on fulfilling their own appetites and desires, offers a wholly negative outlook on the male sex. Again, there is an element of emotional experiment – how does this make you feel? There is an element of the revenge drama here, after all. She’s getting what she deserves, isn’t she? This is another reversal of generic form. The rape revenge film, one of the most troubling subsets of exploitation cinema, has generally been about women visiting violent retribution on their own assailants. Under the Skin culminates in a scene which reverts to the dispiriting visual style of the slasher film, giving us the close involvement in swiftly edited action which has been withheld from us throughout. The Johansson alien is pursued through the desolate ranks of pine trees by a forestry worker, whom she has briefly encountered earlier, and who has determined that she is on her own. The camera cuts rapidly between the two of them, giving a sense of the urgency of the chase, and creating a fearful tension. The man who is after her wears a huge, thick, high-vis coat, another armorial hide which exaggerates the size of his body and shrouds his ordinary, human frame in an intimidating, monstrous skin.

The final scene, whilst hardly comforting, has a certain bleak poetry to it. The alien form beneath the skin is revealed, only to be set alight in a petrol-soaked pyre. But perhaps this is only one further layer, burnt away to free something more formless beneath. There remains something unknowable about this being, as there remained something unknowable about the humanity which it had adopted as a disguise. This unknowability, the inability to get to the true core of being, the heart or essence, is the indeterminate conclusion of the story – and not necessarily a wholly downbeat one. Fire burns on snow, ashes mingle with the flames, elements coalesce in an alchemical admixture which promises some new combination. This landscape mirrors the opening images, a return to the human form abstracted, transformed, a drifting part of its surroundings. It’s a climax fitting for a film concerned with death, transfiguration and the deceptive nature of surface appearances. At this point, I realised what the film reminded me of: the emotionally intense, poetic and death-haunted SF short stories of James Tiptree Jr. (aka Alice Sheldon). The final images, with the camera rising to follow the path of the spiralling ashes into the snow filled sky until flake and cinder are indistinguishable, can be summed up by the title of one of Tiptree’s finest, most overwhelming stories – Her Smoke Rose Up Forever.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)