The Unit Delta Plus studio

A Sound British Adventure, broadcast at the very domestic hour of 11.30 in the morning on Radio 4, the optimum time for the unwitting absorption of deceptively experimental sound, was a brief scan of the development of electronic music in these isles in the 50s and 60s. It was presented by the comedian Stewart Lee, who introduced himself as ‘the only friendly e-list celebrity they could find who’d been to a Stockhausen concert’. In fact, he’s eminently qualified for the gig, having displayed a long-term, wide-ranging and well-informed interest in the esoteric borderlands of music. He wrote the Wire Primer on The Fall, won Celebrity Mastermind with a specialist round on the free improvisation guitarist Derek Bailey, produces short reviews for the Observer of albums by the likes of Matana Roberts, Boris, Trembling Bells, Epic 45, Muhal Richard Abrahams alongside the Fingerbobs soundtrack, wrote the introduction to a biography of free improvisation saxophonist Evan Parker, who he also included in an evening of free improv he curated for the Cheltenham Jazz Festival, and took part in a performance of John Cage’s chance-based composition Indeterminacy (he read the texts which form part of the piece). His recent shows, in which he played a Krautrock selection including Kraftwerk, Neu and Amon Duul as interval music, ended with a Carpet Remnant World transformed into a model utopia, the tubular discards becoming dream towers shining with cheerful points of light, all set to the gorgeous, deliquescent electronic melodies of Ghost Box artist The Advisory Circle’s Now Ends the Beginning, the opening track from their brilliant recent album As The Crow Flies (also reviewed by Lee in The Observer).

The programmed anchored the early development of British electronic music in the experiences of war, making the point that much of the technology used was army or navy surplus equipment. Tristram Cary, whom we hear in an archive interview from 1972, was an ex-navy man who perceived the musical possibilities of electronic sound whilst listening to the whistling undulations of short wave radio signals. Desmond Leslie (a collection of whose eccentric experiments was released on Trunk Records a while back), another electronic music ‘hobbyist’, was an ex-Spitfire pilot and UFO enthusiast who, like Cary, cobbled together his apparatus from redundant forces’ equipment and whatever else could be put to use. The amateur status of these early pioneers is emphasised, and comparison made with the electronic composers on the continent, who received state funding to make ‘serious’ works of art at the studios of French station ORTF (the Office of French National Radio-Television) and West German National Radio in Cologne. Over here, Daphne Oram was producing electronic music to sell washing machines and OMO washing powder, and the largely unsung Fred Judd (whose very name conjures up an unpretentious, artisanal approach to sound creation) was producing the first all electronic score for the ITV puppet-based children’s science fiction series Space Patrol in 1963 – the same year that Dr Who first appeared on the nation’s screens with its Radiophonic Workshop produced theme music and sound effects. The story of the Radiophonic Workshop and its involvement has been told on several occasions already, and this programme, after an essential acknowledgment of its massive contribution, turns its attention elsewhere.

Would early British electronic music be so well-loved were it not for its utilitarian, semi-amateur status? Probably not. It certainly wouldn’t have been heard by so many people had it taken the European route to subsidised art music. After all, the likes of Stockhausen became a byword for unlistenability amongst the general public in the late 60s and 70s, even turning up as the butt of jokes in Man About the House. Some of the British composers did feel frustrated at the limitations imposed upon them by commercial or soundtrack requirements, however, and yearned for the artistic freedom afforded their continental counterparts. Peter Zinovieff, the co-founder of EMS (Electronic Music Systems) and inventor of one of the earliest successful models of synthesiser in the 60s, admits that he was ‘rather snobbish’ and was far more interested in the possibility of Stockhausen visiting his Putney studios than in Paul McCartney and all the other pop stars parading through in the late 60s, wanting try out his new instruments. Tristram Cary is cited as being another of the real progenitors of British electronic music, and he was capable of producing both abstruse modern classical music and popular, accessible film soundtracks. His music for the 1955 radio play The Japanese Fisherman, a little of which is played on the programme, was the first electronic score to be commissioned by the BBC, and evoked the solar burst of the first atomic bomb. In the same year, he produced his darkly sardonic score for the Ealing comedy of post-war seediness and decline The Ladykillers, which seemingly had little in common with such electronic experimentation. Although it could be argued (at a considerable stretch) that the sounds of the trains which are a constant sonic presence in the film call to mind Pierre Schaeffer’s early work of musique concrete Etude Aux Chemins de Fer, built up from the recorded sounds of steam locomotive. Trunk Records have released an excellent compilation of Cary’s music, It’s Time for Tristram Cary, which includes the collage-style soundtrack, mixing electronic, jazz and light styles, that he produced for Don Levy’s fascinating 1967 promotional short Opus (which you can find on the bfi COI – that’s Central Office of Information - collection A Portrait of a People).

Peter Zinovieff is one of a number of people interviewed for the programme, others including Radiophonic Workshop composer Brian Hodgson, Portishead’s Adrian Uttley (who also featured in the BBC4 Radiophonic Workshop documentary Alchemists of Sound), Radiophonic Workshop archivist, historian and composer Mark Ayres, and senior lecturer Dr Michael Grierson, the director of the creative computing course at Goldsmiths College who also looks after the Daphne Oram archive held there. Zinovieff is brusquely frank about the productions of his past, dismissing his alliance with Brian Hodgson and Delia Derbyshire in Unit Delta Plus as having created ‘terrible music’. His offhand manner, which displays a disinclination to temper raw opinion with tact or politeness, leads to refreshingly unvarnished recollections. He makes no pretence at having liked Daphne Oram, or of having enjoyed any kind of professional relationship or sense of shared artistic principles or interests. ‘I found her rather dull’, he says, ‘a bit schoolmarmish’. There’s a hint of disgruntlement at the attention she has received recently, and the central position that she and her Oramics machine have been granted in the story of British electronic music as told in the Science Museum’s Oramics to Electronica exhibition. He dismisses the Oramics machine (which derived its sounds from photographically reading waveform shapes drawn onto slides) as a ‘completely wild idea from someone who wasn’t very scientific’. Zinovieff was evidently a musician for whom science and electronic music creation were inseparable, with composition taking on the quality of semi-mathematical, machine-aided calculus favoured by his idol Stockhausen. He liked nothing more than to retreat into his EMS studios in Putney to work, playing with the possibilities of sound generation and developing the next generation of synthesisers. He proudly pointed out that the money from the sales of EMS synths, which became very popular with the likes of The Beatles (he even sold one to Ringo and gave him a few lessons) and Pink Floyd, was all channelled back into the studio.

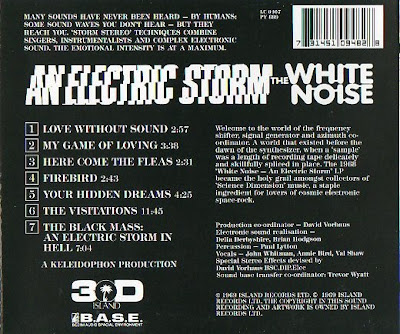

Brian Hodgson’s view of Daphne Oram was a little more generous. He described her as ‘a lovely lady, completely eccentric’, and praised the Oramics machine as being a revolutionary idea, with potential ‘unmatched ‘til the Fairlight’ (the first real fully integrated computer music system), and an idea which worked on a practical level at that. Michael Grierson played an unnamed piece from the Oram archives which documents her first attempts at producing sound from her newly constructed synthesiser – the first tentative steps towards a new music. Hodgson is also a little kinder on the brief lifespan of Unit Delta Plus, citing the music which they created for two Shakespearean productions at Stratford (Macbeth and King Lear) and for a production of Medea at Greenwich Theatre. Electronic music was evidently better suited for tragedies. He also recalls the White Noise LP An Electric Storm in Hell which he made with Delia Derbyshire and David Vorhaus, and the 1967 multi-media ‘happening’ the Million Volt Light and Sound Rave at the Roundhouse (which predated the better known 14-Hour Technicolor Daydream at Alexandra Palace by three months) to which Unit Delta Plus contributed, along with Paul McCartney. His Carnival of Light, a 13minute improvisation with tape effects produced with input from the rest of the Beatles, was made especially for the event. McCartney had paid several visits to Zinovieff’s Putney studio, once more demonstrating that he was the Beatle most interested in avant-garde and experimental art and music beyond the comforting bounds of rock at this time.

The adoption of electronic music, and the EMSVCS3 synthesiser in particular, by rock and pop musicians in Britain really rounds the programme off. By this time, it had entered the musical mainstream, adding interesting new colours and providing expanded possibilities for sound creation. The pioneers’ work was done. As Lee points out, electronic music is now ubiquitous, its means of production accessible to a far wider range of people via PCs and laptops. New tools tend to lead to new music, as Adrian Uttley points out. But, as Zinovieff adds, making good music still ‘depends on your imagination’. The tools may change and become more sophisticated and easier to use, with a bewilderingly vast palette of potential sounds, but the roots of inspiration remain the same. The programme is available to listen to for another week or so over here.

2 comments:

Great show - also featured a number of tracks from 'The John Baker Tapes' CD / LP on Trunk

Was the first electronic score to be commissioned by the BBC, and evoked the solar burst of the first atomic bomb.

Transmission Shops in Fort Lauderdale

Post a Comment