Walking towards the Jacobean pulpit at the south end of the rood screen, we paused to look down at two memorial stones embedded in the aisle, its darkly grey, granite surface worn smooth by centuries of shuffling feet, some soled in patent leather, some bare and roughly calloused. Under us lay whatever remained of Peter Bauwlen and Hugo Cadbury, who died in 1653 and 1658 respectively. The hard surface was inscribed with crudely chiselled, tersely rigid letters, curves and cursives kept to a minimum. Some of the symbols looked almost runic in their stark, sticklike linearity, particulary on the Bauwlen stone, around which they created a decorative border, the centre left a stony void. A number of small letters were interposed between larger ones on the Cadbury stone, mistakes corrected as the stonemason spelled his way around the border, no doubt cursing his negligence. The ultimate effect was highly striking, however, even if amateurish in its artisanship. They both looked a good deal older than the carved dates indicated.

The Jacobean pulpit itself was a solid, boxlike affair with straight-panelled sides. They might have gone on to form an octagonal pen if the structure weren’t neatly constructed to fit into a nook in the wall. It would have looked rather like an oversized music-box, in fact. There was a sounding board on top, a flat, protruding ledge from which the preacher’s voice was intended to bounce, disseminating outwards to reverberate in the ears of the congregation. This emphasis on clarity and projection indicated the increased importance granted to the word and to the sermonising of the local minister in the post-Reformation world. The pulpit had moved out from the sacristy and the minister (priest no more, in name at least) now conducted the service from in front of the screen. The division between priesthood and laity was supposedly narrowed, the minister leading his flock directly, on a much more personal level. The sermon was a central part of the new service, an address during which the vicar could, if he was a skilled speaker, inspire and make intimate spiritual and social connection with the faces looking towards his corner speaker’s box. An iron bracket extended forward from the pulpit’s lip, the ledge on which the passionate preacher might lean to emphasise a point, adopt a pose of casual intimacy or get closer to his audience. The bracket would have held an hour glass, just to remind him not to get too carried away with the message. It was also a standard memento mori symbol. Make your point, for we none of us have too long in this place.

Behind the pulpit, a narrow arched entrance in the wall opened upon a set of steps, ascending in a steep spiral within a constricted, whitewashed well. We carefully crawled up this chalky, snail-like chamber, feet planted sidewise on the narrow precipices of the stone stairs. They soon unwound onto the top of the rood screen, stone turning into wood. Before the Reformation, there would have been a loft built on top of the screen in which lights could be lit and incense censers swung, and from which the choir could sing and decorations could be hung. It was another level of the medieval church’s multi-platform, multi-coloured, multi-sensory theatre. Now it was a creaking, dust-carpeted expanse of bare wooden boards which looked and sounded none too safe. An old loudspeaker with brown woven grill was placed aslant in the middle, a brown wire snaking across the length of the screentop from its blocky hardwood cabinet – a lengthy rat’s tail. This was the kind of hardy megalith which used to get heaved out for village fetes in the 1950s. Its top was a plateau strewn with an accumulated tilth of droppings (church mice presumably) and dead flies. A message was scrawled in fading biro on a piece of paper loosely attached with yellowed sellotape. It requested that the speaker not be moved from its current position. It looked like that instruction had been followed for a good many decades.

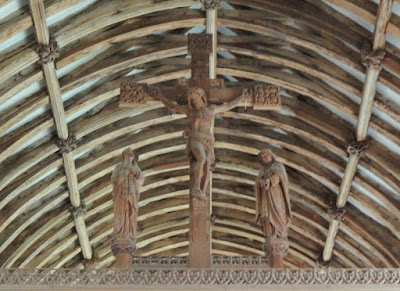

Treading creakily and cautiously along this wooden parapet, we peered down into the rear part of the church, the sacred chambers behind the screens. On the north wall of what appeared to be a largely empty chapel we could see shapes painted in a dull red tone, all gathered around the central divisions of a crucifix. The rood crucifix atop the screen also loomed large above us, its transverse beam cutting across the line of the sloping roof joists a few feet overhead. The Marys stood to either side, adding a female symmetry to the scene. From the rear, their wooden haloes looked like the discs of caps or berets, attached at a chic, acutely angled slant. We edged towards a precipice overlooking the aisles, like guards on a defensive gatepost dividing the sacred city of the chosen ones from the secular lands beyond. From up here, we could get a close look at the wooden statues. Something strange immediately caught our attention. Pendant from a loop of cord hung onto a nailhead in the centre of Christ’s pierced hand was a sharp, white shard. On closer inspection, it proved to be what we had suspected – yes, a sliver of bone, long and tapered, like a canine tooth, roots and all. Who had climbed up here to hang it from Christ’s wounded hand? And what was the nature of their offering? A charm to cure some debilitating illness? Or a token to commemorate the centenary of the Great War, strung from a statue itself erected in the war years in remembrance of one fallen on the fields of Flanders. It swayed gently in the currents of air playing around the church rafters, as if the hand to which it was attached was faintly stirring with vestigial spasms of reflexive muscular movement. Whatever its provenance, it possessed an eerie and slightly disconcerting power. We decided to descend, taking special care not to tumble down the steep, narrow-stepped stairs and barrel out in front of the trinity of decapitated saints.

Back on ground level, and on solid flagstones covering the memorialised dead, we walked to the screen doors which led to the wall painting we had glimpsed from above. A wooden latch on the back swivelled upward, as it must have done countless times over the centuries. The doors seemed reluctant to open for us, however. I in turn was reluctant to apply too much pressure, fearful lest the carved and painted medieval wood should crack and splinter at my blundering touch. But a slight shoulder budge proved sufficient. We walked through, crossing the border into the sacred, and were rewarded by the incredible panel paintings on the rear of the rood screen – a surface known as the parclose screen. These were granted a larger area than the rood saints, less compressed by Gothic arches and decorative traceries. There was some Reformation damage, mainly to the eyes (strike out the gaze! Destroy the vision!). But otherwise, they were remarkably intact. The large panels told the story of the incarnation, with annunciatory angels, heralding prophets and an apocryphal guest star role for Mary’s cousin Elizabeth, who also becomes pregnant, though previously barren. Mary herself is seen kneeling piously at a lectern with bible or prayerbook open before her, and later sitting beside Elizabeth, both contentedly cupping their hands around each other’s full-wombed bulges.

The figures are dressed in the fashions of the 15th or early 16th centuries, floppy, trailing caps and capacious tunics, belted and rippled with folds. Such extravagant us of fine cloth was a deliberately ostentatious indicator of wealth and status. The hands are set in varied and highly expressive gestures. These are storyteller’s hands, bringing the words of the miraculous tale to life. The contemporaneity of the panel figures made the story more immediate to the congregation; or at least to the few who were privileged to pass into this privileged space. Perhaps the finery they sport was intended to reflect the rich raiment of those who were allowed to cross the sacred border. This was once the Chudleigh chapel, so you would have to have been of a certain standing. The paintings strongly resemble comic book panels – the panels in this instance being wood rather than pulpy paper. Instead of speech bubbles, the characters bear unfurling scrolls and pennants on which the holy words are inscribed in a gothic script. The star-eyed figure who might be a portrait of a murdered monk lightly grasps a forked ribbon-end between fingertips and thumb. It flutters up and around him, s if possessed of a living agency, an innate impulse to reveal the Word which defines it. ‘Omnes resurgent in novissima tuba’, it proclaims. ‘All will rise up at the last trumpet’. The mild monk points to the paper weakly clutched in his right hand, as if to draw attention to his own eventual resurrection, to reassure himself of his place in Eternity.

Turning from this narrative sequence of panels, we look at the outlined remains of the 15th century wall painting. This is more condensed, all the symbolic information packed into the space surrounding the cross. The abstracted objects associated with the passion, which are often found carved on medieval bench ends or etched into stained glass, float around the central symbol of Christian faith like electrons orbiting an atomic nucleus. Of the original palette, only the umbrous red now survives. It was revealed when the Chudleigh memorial was removed from what was then the family chapel into the aisle. It’s a dim reminder that the whole church would once have saturated the eye with chromatic brilliance. All walls and surfaces would have been decorated, painted with patterns and biblical scenes, illuminated by light spectrally tinted from its passage through coloured glass.

We step through into the sacristy, and are penned in by wooden walls. Victorian angels look down on us from the corners of more wooden screens around the altar. They are gilded with light shafting through the clear, diamond paned arch of the south window, haloed by the blue and vermillion hemispheres of stained glass roundels behind the altar. Positioned halfway between the ground and the roof, they give the enclosed space a feeling of elevation, of being apart from material reality but not yet ascending to the celestial plane. An inbetween space, a hallway connecting separate states, body and spirit.

We leave the sacristy and the old chapel, pushing open the creaking oak doors, temporarily parting Mary from the Angel Gabriel. Taking a few steps up the northern aisle to the west end of the church, we pause to contemplate the Chudleigh memorial, whose removal had revealed the ruddy crucifixion. A large wooden board painted in funereal black with lettering shining out from the shadowy background, it is crowned with the family crest, flanked on either side by wild men. These are folkloric figures of the wildwood, tousle-headed and bushy-bearded, their modesty (or the modesty of the onlooker) sparsely preserved by shorts woven from branches and leaves. They carry gnarled clubs with them, which suggest a lineage deriving from Hercules, and also an affinity with the less modest Cerne Abbas giant, the priapic chalk hill figure in Dorset. They are free spirits, bound by the laws of the natural world with which they are inextricably enjoined, but not by the rules and conventions of human civilisation. In some ways, they are mythic progenitors of Rousseau’s noble savage, the outsider uncorrupted by the taint and compromise of society. Reversing the fall, they return to the garden, now overgrown to become forest. Some parallels might by drawn with the encampment of travellers currently residing in the Haldon forest.

Towards the bottom of the board, we find some of the traditional memento mori symbols, reminders of mortality and prompts to use our short earthly span to its fullest effect. A pair of scythes is crossed, the blades facing outwards as if they had been leaned carefully against a wall, their work done. Even the Reaper has to rest from time to time. On the opposite side to the scythes is an hourglass, pictorially rhyming with the timer which would have nestled in the iron bracket holder on the pulpit. Perhaps the congregation, watching the level of sand diminish with agonising slowness from the upper chamber, fell to contemplating their own inevitable end. At the base of the board, buried beneath the writing, is a skull, square-jawed and blockheaded, and with a few teeth missing – a distinctive detail which suggests specific portraiture. It is painted gold, a gilded death’s head which acts as a gatekeeper, a guide to the golden fields of eternal life.

The memorial is for George Chudleigh and his wife, Lady Mary Chudleigh. Both had significant connections with the Civil War. Mary’s father was Sir William Strode, a prominent figure in the opposition to King Charles. Sir William was at the heart of the parliamentary melee of 1629. The speaker was held down after refusing to read a resolution against the arbitrary imposition of warmongering taxation, and the rebel members ignored an order to leave the chamber. As a result, Sir William was sent to the Tower and imprisoned in various locations for the next 11 years, an absolutist period during which parliament was never assembled. His incarceration didn’t diminish his determination to stand up to the king. In 1642, he was one of the Five Members of parliament whose impeachment under accusation of high treason set the accelerating progress towards civil war in motion. When the king himself entered the chamber to make the arrests, only to discover the offending parties had absconded, forewarned and sheltered in the labyrinth of London, he realised that he was no longer in control in the capital. He left for Oxford soon afterwards, there to form his loyalist splinter parliament. Sir William Strode died in 1645 and was given a public, formal burial in Westminster Abbey. In the vindictive retributions following on from the Restoration in 1660, his body was exhumed, his monument now residing in St Mary’s Church, Plympton.

Sir George Chudleigh was directly involved in the progress of the Civil War in the local area. He was initially a Parliamentarian, a general in Cromwell’s army. However, his son James, also in the Parliamentarian army, was captured by Royalist forces in the early stages of the war. A man whose pragmatic realism outweighed any ideological principles, he immediately switched sides. It was a change of heart which he communicated with sufficient conviction to receive a commission as a colonel in the king’s army. Sporting a turned coat was eminently preferable to a sword in the guts, even if the colours didn’t quite suit. He was duly accused of treason by Cromwellian generals; a traitor, but a live traitor rather than a loyal dead man. His father, deciding that blood and family honour were more important than political allegiances, resigned his commission and joined James on the other side. It didn’t do either of them much good. James was killed in 1643. In 1645, General Fairfax led the New Model Army into the south west, occupying Topsham and lodging in Ottery St Mary for the bitter winter. When they pushed west again in early 1646 to pursue Royalist forces, they took over the manor of Ashton, a tactically commanding high spot on the Haldon ridge from which to prepare for a sweep down into the Teign Valley and north west to Torrington. It was here that a decisive battle would be fought, the pronounced victory for the Parliamentarians bringing the war in the south west, and in the country at large, towards its conclusion.

General FairfaxIt was a time for George Chudleigh to make himself scarce. The supposed bullet holes in the south porch door would have been created at this time, if at any. Truth to tell, they look a little too neat to have been made by the explosive impact of a musket ball, a burning pellet of iron liable to violently splinter bone or wood. But peering through the holes from the inside to the light on the hills beyond, I feel inclined towards the vagueness of romantic legend and local lore rather than the rigour of rational, reasoning. This felt like a place and a moment for imaginative fancy, not empirical deduction. That could come later.

It’s interesting to speculate what tensions might have arisen within the Chudleigh household. Lady Mary was the daughter of a notable Parliamentary hero, after all. The national divisions and local conflicts created by the Civil war may very well have been reproduced on a domestic scale within the marriage, voices raised in anger and argument within the Place Barton manor house down the hill from the church. Whatever dramas may have been played out in the home, however, Lady Mary performed her duty in perpetuating the Chudleigh lineage with heroic dedication and thoroughness, also managing an admirable symmetry and balance in her production of offspring. She had 9 sons and 9 daughters, as her memorial inscription proudly pronounces.

I wonder what a later Lady Mary to marry into the Chudleigh family might have made of this no doubt exhausting childbearing feat. This Mary Chudleigh was born in 1856, during the latter years of the interregnum, but was really a child of the Restoration. She consorted with various poets of the period, and wrote poetry and essays herself. Some of her writing has led to her being claimed as a proto-feminist. But as Angela Williams points out in her insightful piece on the Literary Places blog, it is important to bear in mind the conventions of the time, both literary and social. Witty dispute was fashionable within certain circles, and license could be taken in the knowledge that this was intellectual sport, not the kind of agitation for radical change which had been voiced across the land in the preceding decades. Nevertheless, there is a strong-willed and amusingly sardonic advocacy of female independence of mind in Lady Mary’s poetic dialogue of 1701, written as a terse rejoinder to a wedding sermon intoned by one John Spring in 1699 in which he declared that a woman should naturally be subject to their husband’s wishes within a marriage. It bears the thoroughgoing if somewhat unwieldy title ‘The Ladies Defence: or the Bride-Woman’s Counsellor Answered: A Poem In A Dialogue between Sir John Brute, Sir William Loevall, Melissa and a Parson’. Lady Mary, who died in 1710, doesn’t have a memorial in the church. David had brought along a copy of her best known poem, To the Ladies, however, and stood before the Chudleigh memorial to read it out. Her words rang round the spaces of the church, given substance by David’s soft Mancunian tones, and formed their own epigrammatic tribute:

Wife and servant are the same,

But only differ in the name:

For when that fatal knot is tied,

Which nothing, nothing can divide:

When she the word obey has said,

And man by law supreme has made,

Then all that’s kind is laid aside,

And nothing left but state and pride:

Fierce as an Eastern prince he grows,

And all his innate rigour shows:

Then but to look, to laugh, or speak,

Will the nuptial contract break.

Like mutes she signs alone must make,

And never any freedom take:

But still be governed by a nod,

And fear her husband as a God:

Him still must serve, him still obey,

And nothing act, and nothing say,

But what her haughty lord thinks fit,

Who with the power, has all the wit.

Then shun, oh! shun that wretched state,

And all the fawning flatt’rers hate:

Value your selves, and men despise,

You must be proud, if you’ll be wise.

Having invoked the bright spirit of this singular member of the Chudleigh clan, it seemed an appropriate moment to take our leave of the aisles of Ashton. The sun was shining through the clear glass of the southern window, illuminating the medieval panels in the north. They glowed dully through the fogging grime of the ages, the trees in the graveyard beyond looking like further diamond framed outline etchings of green tracery. The light suggested that this would be an appropriate time to take a circuit of the church exterior, wandering amongst the graves.

The graveyard was in fact quite a compact acreage. On the north side, it accommodated itself to the slope of the hillside, whose steep declension we would soon be merrily sailing down. The stones on this side of the church were noticeably more wreathed and crowned by ivy, skirted by brambles, bracken and thickly clumped grass. This was, after all, the Devil’s side, the poor end and, more practically, the area in the shadow of the church’s stone mass. It was slightly more expansive than might be expected for such an undesirable post-mortem residential district. This was due to an extension of the boundaries effected in 1907. The lower part might therefore be thought of as the suburbs of the dead.

Amongst Celtic crosses, gothic arches and stone beds in the original neighbourhood, our eyes were drawn to a small, black iron cross of a Germanic cast. A central disc was bordered by arms and a crown which could have served as axe heads with a little sharpening. The name on the circle was Ada Alford, a monciker suited for a songbird of the Edwardian music halls. The dates weren’t included. They were obscured b springy tufts of grass at the base of the cross. I carefully parted them and peered closely to uncover evidence of Ada’s time on Earth, the period in which she lived. For a moment I read the inscription as stating that she’d died at 12 years of age, and a lump rose in my throat. Then the one resolved in my failing eyesight into a 4. Still not a full span, but at least she must have enjoyed something of the world. So Ada, with your humble iron cross in the shadow of the north side and of grander memorials, I hope your life afforded you pleasure and a measure of contentment.

Circling back to the south side, we walked into sunlight once more. David found a lichen covered twig and used it as a beater for the triangle he’d brought along, testing out the resonances of stone recesses and corner nooks. We knelt down to inspect lichen universes sprayed across the flat planes of gravestones, blossoming in orange, lime and purple globular clusters and nebulae. There were also wavy, intersecting kelp fronds of deep green moss and anemone-like fans and rosettes of lichen which were suggestive of undersea worlds, mites and ants transformed into crabs, shrimp and other scuttling and paddling crustaceans. We speculated on the linguistic connections between lichen and the word lych (as in lychgate), derived from the old English for the dead, lic. Lych ways, or corpse roads, such as the one leading across Dartmoor from Lydford to Postbridge, were the paths of the dead, routes along which bodies would be borne for burial. They were generally winding, avoiding a straight, linear route in order to confuse spirits who might be tempted to return and haunt the living. Lich was also a word coined by 20th century writers of the weird such as HP Lovecraft, Fritz Leiber and Clark Ashton Smith to refer to revenant corpses, often reanimated by magical means. The green-painted slopes of the lychgate roof were clustered with copses of tiny moss forests, a miniature landscape model of the wooded hills beyond the churchyard and village. Beneath, billowing hammocks of spiderweb spread their complex cat’s cradles across the eaves. They catch the low-angled rays of the late afternoon sun, the spidersilk glinting and shimmering.

We passed beneath them and descend the zigzagging stair, untethering our bikes from the noticeboard at the bottom. And off we went, sailing down the western slopes of the Haldons, past the big old medieval barn, now renovated and turned into something modern and fancy, a place for conferences and retreats rather than cattle and sheep. We also whooshed past the entrance to Place Barton, the former residence of the Chudleighs. Near the bottom of the hill, we paused at Lower Ashton. Essentially a pub and a post office and store, it was a reductio ad absurdum of a village, condensed into its essential form. David popped into the village store to replenish his supplies and pass the time of day, and then we pushed off, forgoing the temptations of the pleasant-looking inn. We crossed the river Teign via a medieval packhorse bridge, bracketed, angular nooks placed along its span to retreat into should a haywagon happen to be trailing over. They also provide excellent vantage points from which which to spot river birds. Some weeks later, I watched a young dipper bobbing about on a rock, making its first attempts at fishing solo. It seemed to be doing quite well, a promising start to its dipping life.

On the other side of the bridge, we immediately turned right onto a road which paralleled the course of the Teign, running upstream through the valley. It wasn’t a particularly busy road, but after the sleepy country lanes we’d been traversing, it seemed like a return to the busy rush of the modern world. It was only a mile or so before we found ourselves turning towards Doddiscombsleigh, however, retreating once more to the quiet old roads meandering their slow way around the folds of the hillsides. A clear moon, waxing towards fullness, now hovered pendulously over the treelined brow of Scanniclift Copse, rising above the Teign, which we had once more crossed (along with the derailed course of the old railway line). We were entering a magic lunar valley, our approach heralded by the coarse, rasping fanfares of rooks. Up and down the road undulated, with the moon a watchful orb above us, measuring our unhasty but steady progress. By the time we reached the village of Doddiscombsleigh, the light was failing, dusk beginning to extend its crepuscular tendrils. We made our way directly to the church, resisting the temptations of the Nobody Inn for now.

We approached the church up a narrow gravel path and walked through the unwalled graveyard. Heading into the porch and opening the door (which was of fairly modern vintage), the first thing we saw, facing us in the northern aisle window, was the figure of St Christopher, etched and outlined in stained glass. St Christopher was an icon imbued with great power for the medieval Christian. Not only was he the patron saint of travellers, looking after the weary wanderer, but a glimpse of his image would provide protection against death for the remainder of that day. Small wonder that representations of St Christopher were often placed opposite the entrance door in medieval churches, making this the first thing the congregation would see as they filed in. Here he was a bearded giant, the infant Christ like a tiny bird on his shoulder. His staff was a thick tree trunk, budding and shooting into life at the top. He looked like another version of the wild men we had seen on the Chudleigh memorial.

More sprouting greenery was to be found on a foliate head looking down from a capital on the westernmost column of the south aisle. A fascinating account by a local doctor outlined the possible symbolism and folkloric significance of this singular carving. It had a noticeable harelip, thought to be one of the Devil’s characteristics in a fearful, superstitious time when difference was demonised (and have things really changed so much?) The elongated leaves, with their serrated edges, are devil’s bit scabious. Together with its placement in the shadows furthest from the altar at the eastern end of the church (the side of solar rising) and the pointed, vulpine ears, this suggests that the carved foliate head is a representation of green-ish man or wildwood spirit as Devil. The Pagan figure demonised in this instance, rather than displaying a sense of continuity with the Christian symbolism of death and rebirth.

Another green man at the eastern end of the northern aisle balances out this figure, creating a pleasing sense of symmetry. It’s in the more traditional style, branches and leaves bursting out of the mouth as if from the stump of a felled tree – coppiced human heads. Green men have many moods, as if they metamorphose with the seasons; placidly grazing in bountiful springtime, ferociously predatory during winter scarcity. The specimen here tended more towards the latter end of the spectrum. There’s something feline about it too. A green man combined with one of the black cats of the moor. It also has a roguish Kirk Douglas dimple in its chin.

Baptism

Extreme Unction

Penitence

Edging to the side of this figure, we began to inspect the magnificent medieval stained glass which filled the arched windows of the north aisle and culminated in the thematic kaleidoscope of the seven sacraments window at the eastern end. These windows miraculously survived the shattering stones of the Reformation vandals. People need little license to indulge in the destructive pleasure of smashing glass, so it’s remarkable that they’ve survived intact into the present. Some suggest it’s because Doddiscombsleigh, tucked into the valley folds beneath the Haldon ridge, was so difficult to find that the agents of the reformed church and the later Puritan iconoclasts passed it by. The sacraments orbit the central figure of Christ, a Victorian stand-in for the absent medieval incarnation. He is the Son as sun, drawing all together throughout life’s progress, sacralising its stages of physical, social and spiritual development. Each moment is linked to his stellar body by scarlet streamers of blood which radiate from the five Passion wounds (hands, feet and heart); blood as light and lifeforce. Five lifelines for seven sacraments. The sacraments depicted cover birth (baptism), confirmation (the induction into the body of the church), the Eucharist (the ingestion of Christ’s body), penitence (forgiveness – the confession and absolution of sin), marriage (the union of man and woman and ensuing issue blessed by God), ordination (the continuation of the priestly line), and extreme unction (the last rites ushering the dying from life). The latter was placed immediately below the baptismal scene, the tracking gaze providing a cinematic dissolve from birth to death, the cry as air is first drawn into the lungs to the sigh as it is exhaled for the last time. It’s a juxtaposition carrying its own memento mori message as much as the laurel wreathed, toothless skull at the base of the 1697 memorial to John Babb.

The medieval faces are full of character, imbued with individual life by idiosyncratic details, the variations from the accepted ideal which make them feel real. A penitent’s overbite, the sharply carnivorous set of teeth bared by a priest or the snub nose of a woman keeping vigil by the side of the death bed (the same woman in the marriage panel watching over her dying husband?). Details catch our eye and draw us in for a closer look. The spreading fan of overlaid hands resting on the head of a baby as it is held over the baptismal font; the confirmation-bestowing priest holding a child which looks like a tiny, fragile doll, his fingers pincering its head as if about to snap off part of a gingerbread man. The hands of the couple being married are held together in a wavering grasp suggestive of anemones locking tentacles. I become particularly fascinated by the fashions of the time: the money purse hanging from the belt, the severely fringed hairstyles and, particularly, the shoes, which are rounded and highly practical, not in the least like the absurdly pointed and curled footwear of popular medieval imagery (although there is a more pointy pair elsewhere).

The window was restored in 1762, and one of the glaziers was so proud of his work that he inscribed his name in a pane of blue glass just above the bed of the dying man in the extreme unction scene. P Cole done this window March 1762 whom god preserve amen. The shaky scrawl could have been scratched out by the spidercrawl of one of the charcoal arachnid scribbles outlined against the coloured glass like more fine leaded work. No matter how closely I peered, I was unable to locate Cole’s inscription on this visit. It was only on a return journey some months later that I found this artistic signature on its cerulean shard, part expression of creative ownership, part selfless dedication to God.

We haven’t come at the best time to see them in all their illuminated glory. Their colours don’t pulse with the refracted radiance of the sunlight. But we can get some impression, and peer really closely at the details within individual panes: the watery bubbles, relics of the molten state; the finely drawn black lines of curling hair and folded fabric; and the patterning used in the background, some of which looks startlingly modern in its symmetrical rigour and the care with which colours are contrasted and composed. Stars and diamonds add stylised decorative elements. Paul Klee and Piet Mondrian would have approved and possibly drawn a few lessons. Modernity lurks luminous in the ancient artisanal crafts – the shock of the old.

The colours of the robes in which the saints of England, Scotland and Ireland (at this time still entirely separate nations) are wrapped are particulary beautiful. Andrew’s blue and St Patricks green and red. St George remains pasty and translucent, however, a true English saint, his armour waiting for the sun to make it gleam. Even the cross in his armoured breastplate lacks its customary scarlet. He thrusts his spear down into the maw of a dragon’s head which is similarly pallid, a white cave worm. The dragon is no mythically earthshaking mountain horde beast, more the size of a small alligator. St George’s attack seems almost bullying, just another royal hunt. His spear rips out of the side of the unfortunate beast’s head, its diamond head tip forming an extra ear. The heads of St Peter and St Michael are encased in bubbles which look like the sleek art deco dreams of belljar space helmets. They are von Daniken astronauts, medieval archangels and church fathers on the moon. St Christopher as patron saint of astral travellers. The representation of the Trinity as three crowned kings with suitable regal beards looks like something the saints might encounter on their space travels. They form a coagulated mass, a tripartite being, coronets fused to their heads. Their faces are pustulent with bubbling glass, and they are coloured a forthright shade of yellow. The lumpy custard kings, English mustard gods offering us benediction with upraised index and middle finger (except for the Holy Spirit which, being incorporeal, has no hands).

St Michael is depicted in his end of times role as weigher of souls, his feathered limbs particularly apparent. He holds a large set of scales in one great bowl of which a tiny human figure anxiously crouches. But what’s this? A devil of the classic pointy-eared, fork-tailed variety is reaching up to pull on the scales, tipping the balance in its favour to it can claim this human soul for its master in Hell. Let’s hope St Michael notices its impish intervention. Next to him, St Peter holds a huge key to a door which, if commensurate in size, must be of a truly vast expanse. Its handle end creates what looks like a decorative aperture in his stomach; the hole for a wind-up key, St Peter as clockwork simulacrum. His hair is particularly finely rendered. St Paul leans on the sword with which he was martyred and holds his head as if despairing at the state of all around him. We imagine him muttering a vexed ‘oy’. The hand is probably supposed to be shielding Paul’s eyes against the blinding Damascene vision of the resurrected Christ. It’s difficult not to impose a more comical interpretation, however. St John the Evangelist holds another chalice from which a serpent is uncoiling itself, which we can compare to the one we saw in Ashton. This glass monster, tiny though it might be, is a lot fiercer than the adorable black beastie on the Ashton rood screen. It has a golden head and wings (a miniature Quetzelcoatl), and a stringy tongue furling outwards from its open mouth produces an almost audible hiss of outrage. St John himself has a fine thatch of curly russet-coloured hair, sweeping back in a romantic Algernon Swinburne or Thomas Chatterton tangle. St James the Greater, the patron saint of pilgrims, makes his eternal way with the aid of a stout golden staff. His broad, floppy hat is designed to shade his face from the sun, which the burning corona of his halo resembles. A shell pinned to the folded back brim of the hat makes reference to the Santiago pilgrim route. Did any of the Doddiscombleigh congregation make that lengthy penitential peregrination, I wonder? Mary is here too, her robe an exquisite brocaded blue. She appears withdrawn, caught in an intensely inward moment. She doesn’t look like a figure who would reach out to those devoted to the Marian cult.

The symbolic embodiments of the four evangelists are here, too. The angel of St Matthew, looking rather stern and sulky; the winged lion of St Mark with its lobate tongue lolling out; the ox of St Luke, also with wings; and the more aerodynamically convincing eagle of St John. The angel has been bifurcated by black leaded lightning, the eagle’s glorious plumage is speckled by sooty deposits, and the ox has the cracked charcoal star of a dead spider above its folded wing. Droplets of thick glass beneath have a deep subaqua glow, pearlescent greens and turquoises giving the impression that we are looking through a porthole into oceanic waters. Another quirky creature can be found in the heraldic form of a two-headed black bird. It looks like a mutant cormorant, a friendly companion, possibly possessing the power of speech. Some of our Ashton saints return in the upper panels, too, still bearing their implements of torture. Here is laughing St Lawrence with his gridiron, St Stephen with his stones and St Blaise with his combing iron. The red, blue and green backdrops look like theatrical curtains for their restaged dramas.

The Victorian glass in the east window is inevitably overshadowed by the stunning medieval glass, but it is splendid in its own right. It depicts the angel in Christ’s tomb revealing his resurrection to the women who have come to attend to the body. The faces look very contemporary, and the angel could be one of Hitchcock’s cool blondes. There’s something of Grace Kelly in it. It’s arm is raised heavenward with a casual, matter of fact insouciance. The walls of the cave are layered in strata of purple and vermillion, and the ground beneath the women’s feet is carpeted with vividly rendered daisies, cornflowers, marigolds and irises. Colourful life blossoming in darkness, in the shadow of the tomb.

Doddiscombleigh also offered some fine carved medieval bench ends, including one featuring a cocky lad, a local bravo, perhaps. He is quite the peacock with his patterned cap, buttoned up shirt and broadly frilled collar. His shoulders are set at a swaggering angle, mouth curled in a 15th century Elvis sneer. Well uh-huh. He was centred in a circular frame, as if this were a magnified medallion. Some things never change. There’s something very photographic about this portrait, the carver producing a naturalistic pose which feels like a moment of passing life captured and preserved. There was also a shield bearing a heart pierced through by two crossed spearheads. This is one of the symbols of the Passion, a fuller selection of which we had seen in the medieval wall painting in Ashton. Passion symbols in the form of a pierced foot, hand and heart also featured in a small, much begrimed panel of stained glass in the upper section of one of the windows. Another carved wooden eagle looked beakily across at us from the lectern near the altar at the eastern end, watching our investigations with a warily assessing eye.

We left the church interior and walked out into the gathering gloom of dusk. House sparrows were noisily gathering in the ivy thickets entwining an old telegraph pole in the far corner of the graveyard (the local exchange for the underworld). It looked and sounded like the dead tree bole had come to life again, sprouting an odd blend of vine, twig and coloured wiring. The sparrow’s roosting told us that it is high time we repaired to the Nobody Inn. In the cosy nooks of this centuries old hostelry, we partook of the local ale and were regaled with the fascinating tales of its history – of the provenance of its remarkable selection of whiskies in the wartime posting of the landlord to the naval bases in the Scottish highlands.

It would have been all too easy to settle down for the night before the fireplace. But we still had to make our way back over the Haldons and down into Exeter. So off we set into the rainy night, fuelled by good ale and the residual warmth of the inn’s fire, aglow with the knowledge of a quest fulfilled. The clouds soon parted and our path was lit with soft moonlight, the woods around us haunted with owls and the furtive rustlings of night creatures. As we passed beneath the pylon lines, a crackling electric border of sorts, we looked up and saw mighty Orion glinting coldly in the dark distance. He continued the hill-spanning stride of the iron pylon giants upwards into stellar regions. Soon after, we crested the ridge of the Haldons, passing the white tower (its radiance now occluded) and looked down onto the bleared lights of Exeter way down below. We were leaving the timeless realm of the mythic and descending into the modern world once more. The Ashton Ascension was complete, it was time to return, our spirits refreshed and happy.

Begin your Ascension here:

PART ONE

And continue here:

PART TWO

In memory of Hélène