The white-washed porch was edged with stone benches, so we were able to perch and munch. The entrance arch framed a pastoral view worthy once more of Samuel Palmer, rounded hills rising to an arcing, cloud-grazed ridge with a cluster of sheep positioned with picturesque precision to provide horizon cut-outs. Bird song suffused the spring air, a complex foreground sound mesh against which the background blether of sheep added a less sonorous ground. On the moss-blanketed mound stretching out before the headboard of a gravestone, a small violet was illuminated in a beam of sunlight, a vivid pulse of life in this tree-shaded corner.

The porch itself showed traces of previous occupancy by martins, swifts or swallows, ghosts of their darting silhouettes flitting and weaving flight paths across the peripheries of inner vision. Above us, a monster of a spider lurked in the shadows of the eaves, tense with potential lightning-swift energy. Its unfazed quiescence was made possible by the migration of the swallows at summer’s end. It would no doubt be more circumspect upon their return, retreating to the darker recesses, scuttling with irritation and muttering through their mandibles. We posed no such threat as we ruminated upon our sandwiches, however.

Oak door bullet hole bleeding lightFrom our stone picnic bench, a granite shelf which must have given hard repose to countless bottoms over the centuries, we were able to inspect the large 15th century oak door, studded with a regular, rusted constellation of diamond-headed iron nails. The field-pattern of nails was disrupted by several neat, round holes, through which we could peer into the interior. Local legend has it that these are bullet holes dating from the Civil War. General Fairfax had led the New Model Army out of Ottery St Mary towards the beginning of 1646, marching them up the Haldon ridge and capturing the manor of Ashton. It was a commanding outpost from which to survey the terrain to the west, a last stubborn stronghold of Royalist power. Descending into the Teign Valley and onward across North Devon and into Cornwall, he would pursue those remaining loyal to the king with fierce determination, bringing the war to its conclusion and clearing the way for the parliamentary interregnum. Peering through from some angles, these tiny portholes circle fragments of stained glass. The bullet holes bleed coloured light.

The door into the south porch is imposing and invites a firm knock upon its solid oak face with the hefty iron ring which serves as its handle. Eerily, upon listening back to his recordings at a later date, David discovered a loud series of phantom knocks and thuds imposing themselves over our rambling lunchtime conversation. A disembodied attempt to drown out our discourse? Everyone’s a critic, even in the spirit world. The modern entrance to the church was around the corner, anyway, so we were denied the pleasure of heaving the mighty portal open with what I imagine would be a long, rustily antique groan, a sound pregnant with thrilling anticipation.

We entered instead through a more modest door in the western tower, equipped with an electronic release system which rejected the charms of antiquity in favour of the security of modern technology. Inside, a circular frame of flattened iron hung above our heads, a trailing chain snaking down from it, ready to rattle with a gothic clatter of shivering links. Presumably designed to corral the bellropes, its rusting, skeletal form nevertheless carried the dark charge of some Piranesian dungeon, particularly as our eyes were still adjusting to the dim light of the church interior. With a pleasing touch of Magritte-like surrealism, there was also a battered old street lantern in the tower entrance – the light of the world brought inside, weathered and extinguished. Where once hissing gas might have ignited into flickering illumination behind smoke-smudged glass, a small cluster of spent night lights was now clustered around the serpent-headed form of a desk lamp. The lantern added to the sense of the tower as a transitional space, a gatehouse which ushered us into the nave and the church proper.

The first object which drew our attention was the font, a solid octagonal block of Beer stone carved with heraldic symbols, the fortunes and privileges of high birth openly acknowledged. Levering up the hefty wooden cover, we noticed sturdy iron brackets sunk into the stone rim. These were witch locks, designed to protect the blessed water in the lead-lined font bowl from theft for use in charms, potions or for darker ritual purposes. Purposes which may well have existed only in the fearful and superstitious minds of villagers and ecclesiastical officials. Witch locks on fonts were ubiquitous in the pre-Reformation era. But their removal was specifically stipulated during the reign of Edward VI, the period when the Reformation’s revolutionary programme of cultural transformation was most vigorously pursued. That dictate was ignored in Ashton, however. Whether this indicates a particular fear of witchcraft being practised in this densely forested area is a matter of speculation and twilight fancy.

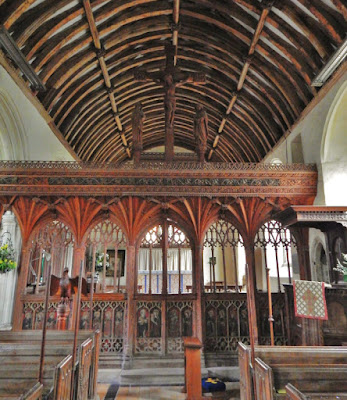

From the back of the nave we gained a broad prospect of the church interior. The eye was immediately drawn to the wooden screen which spanned the breadth of the building, an elaborately carved and colourfully painted barrier spreading from wall to wall. This was the rood screen, and unlike the one in Dunchideock, it was palpably redolent of the pre-Reformation era. The word rood, with its roots in old English, means crucifix, the representation of Christ on the cross. The rood screen was the base for the prominent roods which would have been a feature in almost all churches, drawing the upward gaze of the congregation, an object of power to concentrate the mind and focus the spirit whilst the mysteries of the sacramental rites were enacted behind the screen. They were a prime target for iconoclasm and were, without exception, consigned to the bonfires of the Reformation. A modern rood does surmount the screen, however, giving us some idea of how it might once have struck those entering the church. This one was carved by Herbert Read’s Exeter firm in 1915 and presented in painfully fresh memory of the death of one William Woodfall Melville, a barrister-at-law, on the fields of Flanders in May of that year. It really testifies to all local men who died in the war, however, irrespective of their social standing.

We approach the screen and squat down to inspect the paintings on the panels at its base, framed with gothic tracery in red, green and gold. The light is not good. Another storm is passing overhead and the skies have darkened dramatically outside. Our attempts to locate a light switch only succeeded in activating the dim, orange glow of some antique heaters. The saints and church fathers who line up before us are thus a little shadowy, perceived through the dark glass of time. At some point during our intense, closely peering scrutiny, however, the storm passes, sunlight streams through the windows and the saints come to illuminated life. Some of the blessed company gathered here are familiar, others are far more obscure, occupying seldom explored regions of the sanctified territories.

St George, with neighbour Mary Magdalene

St Michael the Archangel

St Michael slays the 'dragon' (as it looks up at him with eager, puppyish eyesThe dragon-killers are both present, thrusting their spears downward into the roaring maws of the devilish beasts at their feet. St George in his glinting armour, forged and hammered according to the latest 15th century fashions, is shining, immaculately dandified knighthood personified, striking the perfect action pose. St Michael, his feathered limbs giving him a hybrid avian appearance (the celestial birdman) is the archangel who leads the forces of God against Satanic armies in the final battle. He replicates St George’s pinioning downward death strike, silencing the silvered insinuations of Satan’s serpentine tongue for once and all. Scholars versed in the finer details of the medieval bestiary may question why this dragon of Revelation has but two limbs, however. They might point out that this would classify it as a wyvern rather than a dragon. They might very well be correct. St Michael has slain the wrong beast, and Satan has flown free, long, demonically triumphant laughter receding in his wake. A lesson in the value of in-depth and precisely defined knowledge.

St Mark

St Mark's homonculus

St John's poison serpentOther wild beasts rest at the feet of saints, docile and tamed. The evangelist St Mark has what must be his customary symbolic representation, the lion, at his side. However, it has the semblance of a squat, impish demon, reminiscent of the puggish homunculus in Henri Fuseli’s classic Gothic painting The Nightmare. Its mane of spiky, Bart Simpson hair gives it a punk urchin look – a street demon. It’s as if its head, crowned with a flickering beacon of fire, offers a mocking preview of the torments of hell to which it will gleefully drag the souls of the damned. St John is often represented holding a chalice from which a serpent is uncoiling, like a wisping trail of foul vapour. This is a depiction of a legend in which he is handed a poisoned cup of wine, his blessing causing the deadly venom to be transformed into a snake which immediately wavers away. The wee black beastie here looks rather sweet, a mini, coal-dusted dragon which St John seems to be stroking as if it were a pet he carried around in its own goblet nest.

St Anthony (left), with St Ursula, St Leodegar and St ApolloniaSt Anthony is accompanied by his faithful pig, a bristling, tusked boar of the kind which might have been found roaming wild in the forests of the Haldons. Anthony was one of the first of the desert fathers, ascetic Anchorite monks who turned their backs on civilisation and lit out for the wilderness. Anthony’s temptations and torments at the hands, claws and beaks of a menagerie of fantastic, demonic creatures form the basis of a number of feverishly imagined works of art created over the centuries. These range from the symbolic embodiment by Flemish and German artists such as Bosch and Grűnewald of the anguish piercing their plague-ridden times, to the violent unconscious dream scenes of the surrealists, who found such subject matter irresistible. Max Ernst graphically tore the agonised holy man apart, whilst Dali confronted him with a parade of temptations mounted on the backs of elephants teetering on absurdly spindly, telescopically jointed insect legs. St Anthony’s original encounter with his porcine companion was less then friendly. The Devil descended upon his desert cave in aggressively swinish form. But Anthony withstood its Satanic assault, using his sanctified powers, honed through years of ascetic contemplation and self-denial, to purge the creature of its unholy infestation and leave it innocent and untainted once more. The Anthonine order was subsequently associated with pigs from its inception. St Anthony himself is the patron saint of pigs and pig farmers.

The Holy Mother is here, curvaceous and sensual, with full red lips and a satisfied, even satiated look upon her face. She has long, luscious tresses of golden hair, circled with the crown which declares her Queen of Heaven. She is very much the Goddess figure, bringer of fertility and fortune. A plump, happy Jesus sits sprightly upon her knee, a big baby and growing bigger by the minute. In this painting, the source of his strength and spiritual insight seems evident, the roots of Christianity in pre-monotheistic traditions, the female divine, made manifest.

From left: St Leonard, A Sibyl (female prophet), St Stepen, St SidwellA good number of the figures here achieved sanctification through martyrdom. This is sometimes symbolised by the bearing of a palm frond, held aloft like an absurdly ostentatious quill pen. Such is the case here with St Stephen, often considered to be the first Christian martyr. He was condemned by the Jewish authorities in c.34AD for blaspheming - loudly, repeatedly and unrepentantly. The sentence, death by stoning, was carried out with immediate effect, Stephen carrying on with his tirade until he was bloodied and bruised into silence. The three stones he carries, as neatly rounded as cannon or dough balls, are presented as a polite illustration of the means of his execution. These rocks were used to shatter my skull, he seems to be saying, but look, I’m alright now. They never even grazed my spirit.

Many screen saints (the precursors of screen icons to come) proudly bear the instruments of their martyrdom, often presented with an exaggeration intended to foreground their suffering and emphasise its magnitude. They revel in a strange form of stoic heroism based on passive endurance and a refusal to recant the tenets of faith in the face of excruciation and death. The uniform serenity of their expressions and the contemptuous ease with which they hold up their weighty weapons and implements of torture indicates their triumph over their brief earthly agonies, their enjoyment of bliss in the eternal lands. Having endured terrible pain, they are now stronger than ever.

The seemingly morbid preoccupation with the details of torture and death offered (and still does offer) symbolic hope for those suffering lesser pain, fear or anxiety on the earthly plane. The legends of the saints, repeated with storytelling relish until miracles escalated and baroque embellishments flourished, were exemplary tales of people from backgrounds both ordinary and privileged whose piety and suffering had elevated them beyond the mundane world into the realm of the mythic. Like bodhisattvas, their compassion for the suffering of others led them to act as intercessory figures between earth and heaven, the human and divine worlds. A sympathetic magic is at work here – sympathetic in all senses of the word. The means of martyrdom provides a direct line of connection with related pain or misfortune via a system of patronage which became increasingly formalised and codified over the centuries. You would pray to a certain saint for relief, knowing that they had gone through far worse than you and emerged as creatures of immortal power. They would have both personal knowledge and understanding of your suffering and the means to diminish or dispel it. Through and associative logic which seems grimly ironic or ghoulishly funny to the modern sensibility, the martyred saint could be appealed to for prosperity or good fortune in a particular endeavour or livelihood related to the means of martyrdom.

St BlaiseHere we have St Blaise holding the iron comb with which she was raked before being beheaded. As a result, she became the patron saint of wool combers. St Lawrence of Rome wryly displays a toasting fork, as if he’s just about to demonstrate a recipe. He was tortured on a gridiron heated from below by a blazing bed of coals, and is thus the patron saint of cooks, chefs and coal miners. He is also reported to have uttered a quip in the midst of his sizzling agonies; something along the lines of ‘I’m done on this side – you can turn me over’ (wasn’t this included in a Dave Allen sketch?) Such coolness in the face of searing heat added comedians to his portfolio of saintly patronage. Fools or jesters might pray to him for a good reception at court, or latterly, stand-up comedians for courage to face a tough crowd.

St Apollonia, with St Leodegar to her left (he merely had his tongue cut out and his eyes gouged from their sockets)St Apollonia of Alexandria had her teeth smashed or pulled out before she leapt into the fire which had been prepared for her immolation. She grasps a pair of pliers hugely outsized for tooth extraction. A molar which could have been wrenched from the gums of a giant is pinched in its jaws. Apollonia presents it with a slightly sardonic air, as if mocking those who tried to break her. There you go, have that one. The tooth is triumphantly held up as if it were a trophy, a suitably solid symbol of physical suffering transcended by the power of eternal spirit. Apollonia’s image is particularly prevalent in Devon. There was evidently something about her story which struck a chord with the rural populace. She is, of course, the patron saint of dentists, and the person to pray to if you have a toothache.

St Catherine of AlexandriaSt Catherine of Alexandria is a 4th century virgin martyr (a bride of Christ) who is famously associated with the device upon which she was to be tortured – a spiked wheel across which victims’ bodies were laid, their limbs, splayed out across the interstices, smashed and broken by hammer blows. The Catherine’s Wheel is a spinning firework, its spitting jets of flame approximating to the barbs on the wheel’s rim. It also transforms the wheel into a solar symbol, throwing off burning flares, lending Catherine the aspect of a sun deity. The wheel is not represented in the Ashton icon of Catherine. Instead she leans on a hefty sword with a curved cleaver of a blade. Evidently concerned with accuracy and fidelity to the letter of the lore, the Ashton artist has decided to depict the actual instrument of Catherine’s martyrdom. When she was placed upon the wheel, it miraculously shattered, injuring several of the gawping bystanders who lusted after vicarious thrills. And so she was simply and swiftly beheaded. As, presumable, was the wheelmaker.

St Ursula, with St Anthony (and pig) to her leftSt Ursula, another 4th century virgin martyr hymned by Abbess Hildegard of Bingen, grasps one of the arrows with which she was shot. She had set out on a pilgrimage to Rome prior to her dynastic marriage to Conan Meriadoc of Armorica. A largely forgotten figure in his own right, his names resonate in modern ears through their union of the barbaric and mythologically syncreticj fantasy worlds of Robert E Howard and JRR Tolkien. Ursula’s myth partakes of the exaggerations of the Celtic tall tale telling tradition, in which superhuman feats and grandness of scale were used to induce wide-eyed wonderment, a sense that the known, everyday world could unfold and expand to encompass the extraordinary, the plane of the heroic on which everything was bigger, bolder and more emphatic. So, Ursula was accompanied by 11,000 virgin handmaidens, the storyteller relates. The party was ambushed by Hunnish tribes in the territories of Germania and every single one of the handmaidens was beheaded. Ursula was spared this fate, her execution prosecuted by the arrows of German archers. Archers with long, long bows if the size of the arrows presented here were to be taken literally. But as we should now realise, we are in the realm of myth and symbolism, and literalism offers a misguided pespective on the matter (or the arrow) in hand. Needless to say, Ursula is the patron saint of arches, and of fletchers.

St SidwellUrsula’s father was King Dionotus of Dumnonia, the Celtic kingdom of the South West inhabited by the Dumnonii tribe. The Roman name for Exeter was Isca Dumnoniorum, the river of the Dumnonians (in other words, the Exe). So whilst she is generally associated with Northern Europe, and Germany in particular (the grand church of St Ursula is located in Cologne), she is in fact a local figure. Other neighbourhood saints are also gathered here, a martyrs reunion. It was easier to identify with a holy figure whose story was rooted in the local landscape. Particularly notable is the 8th century saint Sidwell, who stands with her scythe planted at her side, its blade arcing out like a battle pennant. St Sidwell gave her name to an area just beyond the East gate of the old city wall of Exeter. She was the daughter of a Welsh lord, Perphir from Penychen, and is also known by the variously translated names of Sativola, Sadfyl and Sidwella. Not specifically a Christian martyr, she fell foul of the jealousies of a wicked stepmother in classic fairytale fashion. This stepmother, Freda, paid a reaper three gold coins to murder Sidwella out in the fields. Sidwella was remowned for her generosity and kindness of spirit, and her resultant popularity inflamed Freda’s jealousy until it was a burning rash of raw hatred. She played on Sidwella’s generosity, inveigling her into taking the reaper’s lunch out to him in the fields. Here, her head was harvested with a swish of the keen-edged blade. For a symbolically significant three nights, a shaft of moonlight spotlit the site of the murder, where body and head lay amongst the cornrows. On the fourth night, the body arose, picked up its head and carried it to the place where it wished to be buried; the site upon which St Sidwell’s church was built. Where the severed head had thudded to the ground, the fresh waters of a spring bubbled up.

St Urith redecapitated, along with St Lawrence and St SebastianIt’s a legend which combines the Celtic cult of the head, believed to be the repository of human spirit and power, and the reverence granted to springs and the holy wells built around them. Ingmar Bergman’s filming of a variant of this mythic pattern in The Virgin Spring bears witness to its widespread dispersal across Northern Europe. There are numerous incarnations of the beheaded Celtic saint who is associated with wells or miraculous springs across the South West. Another figure very similar to St Sidwell can be found a little further to the south in the screen’s saintly cast list, also stood in a relaxed pose with scythe planted upright by her side. The panel on which her head was painted has been removed at some point in time, perhaps during the Reformation. She has been twice decapitated. She is, in all likelihood (unless Sidwella has been doubled), St Urith, Iweryddd or Erth along other linguistic pathways. She was the victim of another wicked stepmother, a character whose malign depiction might represent a repudiation of any residual remnants of female-centred culture and spiritual authority. Her story is very similar to Sidwella’s in its essentials, one interesting difference being that she is decapitated by female haymakers. Where the drops of blood splashed down from her severed head, the tiny flowers of scarlet pimpernels bloomed. The blood is the life, the fertilising water bringing fecundity and a prosperous harvest. There is an obvious connection between these saints and the old harvest myths of seasonal death and rebirth, of reaping, gathering and sowing. Urith’s divine ancestors are Persephone, Isis and Aqhat, Blodeuwedd and Baal. She represents the continuity between the regional observance of Christianity and the cultures and observances which preceded it, the undammed subterranean stream of undifferentiated myth and story. And she is one amongst many.

The Ashton screen is notable for the high proportion of female saints and sibyls in its static parade. This reflected a real need for a feminine facet to be incorporated into a patriarchal monotheistic religion. The aspect of the female divine, the Goddess of birth, renewal and abiding endurance and strength (as well as destruction and division) could not be suppressed and emerged in these coded incarnations. It might seem that the emphasis on suffering and torturous death presents a wholly negative image of femininity. But the visual representation of the women here is strong and calmly self-possessed. They have transcended suffering and proven more powerful and enduring than their brutish tormentors, who sought to wither their spirit and eradicate their affective presence in the world forever. As they still do.

St SebastianOne of the martyr saints most frequently represented in Western art is Saint Sebastian. He is here, towards the southern end of the screen. Unlike his neighbouring saints, he is painted in the midst of his martyrdom. He has always been the object of a certain masochistic sensuality, his arrow-pierced body a focus for sublimated desire, gay or otherwise. It’s a pictorial tradition which Derek Jarman adapted as the basis for his debut feature film Sebastiane (1976). The Ashton artist has taken care to clearly trace plumes of blood spuming from the six wounds created by the arrows embedded in the saint’s torso. Sebastian’s body is set in a relaxed, almost languorous pose, however, stretching sensually rather than knotting in twisted agony. Perhaps his face is transfigured with ecstasies of pain alchemised into transports of joy. We will never know, since the panel on which his head was painted has been removed. It’s not clear whether this decapitation was carried out during the long century of the Reformation or was merely due to subsequent deterioration.

Scarred Sibyl, prophetic vision unimpaired

Scarred St HelenaMany other saints have suffered much more evident damage from the chisels and knives of Reformation iconoclasts, however; secondary violence visited upon them to supplement the suffering of their original martyrdom. The paint could easily have been scraped off, as it was in many churches throughout the country. Or the screen could simply have been torn down and burned. Instead, the zealous vandals, intent on propagandising for the new creed, left the bodies of the saints unmolested. They concentrated their attacks on the faces. Eyes were gouged out, mouths slashed and scored. It was a very deliberate attempt to rob the images of their artistic impact, their ability to communicate with the supplicants who gazed at them. The calm regard of the saints established a direct connection with the viewer, a sense of personal communion with an embodied incarnation imbued with supernatural power. This was anathema to church reformers, an example of arrant popery and Catholic idol worship. The scarring of the face, blinding and making dumb the tutelary saints, destroys the ability to communicate. At the same time, it leaves the body present as a disfigured reminder of what has been roughly cast aside. The blind icons carry with them and implicit threat of violence towards those resisting the new order, to any who might think they can perpetuate old observances.

Scarred St Catherine

Scarred St Sidwell

Scarred St Leonard

Scarred St Blaise

Scarred St Thomas of CanterburyThe seismic shock and massive ideological disruption of the Reformation can be seen and almost physically felt with powerful, hair-raising immediacy in the knife scars and chiselled pits mapping the faces. The intense, violent emotions of the times are still palpable in these savage marks. You can almost hear the curses and effortful grunts of the iconoclasts, the jarring scrape and stabbing knocks of tools on wood, their constructive use turned to destructive ends. A faint resonance of the violent acts of centuries long passed still hums in the still spaces of the church around the rood screen. St Catherine has been given an eye patch, a panel covering her lost orb; St Sidwell’s face is terribly pockmarked, as if eaten away by plague; St Leonard’s mouth has been drilled through, leaving him with a darkened ‘o’, a pursed moue of permanent startlement; his ear has been torn off too, so that he might not hear the pleas of his supplicants; St Blaise has been similarly assailed, and looks like he is whistling or singing an aria; St Thomas of Canterbury has suffered the most terrible damage, perhaps on account of the mitre he wears and the archbishop’s cross he grips. A figure of authority to vent your rage upon. His nose and lower jaw have been sheared off, and together with his hollowed out eyes leave him with a porcine profile. He resembles some of the sketches the artist Henry Tonks made of First World War soldiers who had received terrible facial injuries at the front and had been sent to hospital for corrective surgery.

The tracks of Mary's tears

Milk-eyed angel - GabrielEven Mary has not been spared. Her image on the rear, parclose side of the screen has had its eyes scratched out, as if she too had joined the ranks of the martyrs. A downward score of the knife has drawn the tracks of a tear. The annunciatory angel Gabriel’s pitted sockets have been filled in with white wax, making her eyes look as if they have nictating, cat-like lids. Two tonsured heads, reputedly portraits of monks who had been murdered nearby, were similarly disfigured. One has his eyes starred, lines radiating outwards. They seem to make manifest an expanded vision in a dimension invisible to the naked eye, like the trails of subatomic particles photographed in a cloud chamber; a penetrating higher perception reaching beyond ordinary sight. The Reformation iconoclast slasher has inadvertently lent this particular figure a coruscating aura of extra-sensor power. There are lighthouse beams of vision which could fill the soul with intense, ecstatic illumination or scour it with pitiless, actinic glare.

Star Eyes

Visionary sightWe rise up from our kneeling scrutiny of the panel painted saints and find ourselves confronted with the imposingly massive bible whose blocky weight is borne by the woodcarved wings of an eagle lectern. The eagle’s folkloric powers include the ability to gaze unblinkingly into the blazing light of the sun. It thus became a symbolic conduit of divine wisdom and illumination and was chosen in the medieval period a the ideal beast to bear the weight of the Word and act as intercessor between celestial and earthly regions. The open pages are covered with a small square of aged patterned cloth in silk brocade, its colours faded but still rather beautiful. We lift and gently fold it to see what passage it conceals. The last reading appears to have been from the Book of Ezdras, an esoteric and apocryphal backwater of the bible. Certainly not one familiar to me. Much of the page is taken up with recitations of names, which are filled with potent, poetic richness and round syllabic rhythm. Nebucodonosor, Rathmus and Semallius the scribe, King Artaxerxes and Tebelius, Mithridates and Beeltethmus the storyteller. I feel compelled to read them aloud, and the unfamiliar syllables, no doubt horribly mangled and mispronounced, sound like a summoning. I wonder what strange services are held here, what strange form of religion might have evolved in this remote church in which the pre-Reformation centuries still seem co-existent with the present.

Having bookmarked the page with the only thing which came to hand, a Kendal mintcake wrapper, we essay a bit of bibliomancy, closing our eyes and flicking through the pages before stabbing at a passage with a decisive forefinger. We are not disappointed with the resultant readings. They are both proper Old Testament, full of violent portent and bloody retribution. Mine, from the Wisdom of Solomon, speaks of ‘a terrible sound of stones cast down, or a running that could not be seen of skipping beasts, or a roaring voice of most savage wild beasts, or a rebounding echo from the hollow mountains. These things made them to swoon for fear’. David’s prophetically pronounced ‘behold, the people shall rise up as a great lion and lift up himself as a young lion. He shall not lie down until he eats of the prey and drinks the blood of the slain’. We quietly return the pages to their original passage and respectfully smooth the cloth back over the powerful words. The eagle looks with a stern and piercingly sharp-beaked regard over the nave, its rigidly fixed, concentrated stare admonishing us for ever taking such matters lightly.

Your Ascension begins here:

PART ONE

And descends here:

PART THREE

1 comment:

I am looking forward to part three. Another very interesting place you might like to check out is Steeple Ashton in Wiltshire. Went there last year. Has a lovely Church an old village Lock Up and a disused 1930s garage (pumps intact) I did post a few pics here

https://www.flickr.com/photos/krwdp

Post a Comment